By Chris Wolski

Summary:

Diagnosing lupus remains a major clinical challenge due to its variable symptoms and limitations of standard tests, but emerging biomarkers like TC4d offer significant promise in improving early and accurate detection.

Takeaways:

- Delayed diagnosis is common: It typically takes 4–6 years for lupus to be diagnosed due to symptom overlap with other conditions and lack of a definitive test, increasing the risk of irreversible damage.

- Current tests are insufficient: Standard lupus biomarkers like ANA and anti-dsDNA are either too nonspecific or absent in many patients, leading to missed diagnoses.

- New biomarkers show promise: TC4d, a T Cell complement activation marker, significantly improves diagnostic sensitivity and may transform lupus testing when used alongside traditional methods.

Difficult to diagnose, debilitating, and indiscriminate, lupus offers numerous challenges for patients and physicians alike. Largely affecting women—about 90% of the 1.5 million Americans and 5 million worldwide who have lupus—the disease presents with a wide range of signs and symptoms, including pain, fatigue, and cognitive issues, that could be interpreted as being the symptom of another condition. Or patients could be asymptomatic further delaying diagnosis and treatment.1

In a recent conversation with CLP, Brittany Partain, associate director of Clinical Affairs and Physician Education at Exagen, she discussed why lupus is so difficult to diagnose, the limitations of current testing for lupus, new biomarkers that are speeding diagnosis, and the future of lupus testing.

Her answers have been edited for length and clarity.

CLP: What makes identifying lupus both so difficult—it appears up to a quarter of patients may not be identified at least early—and what is the current time frame for patients to be diagnosed? What are the consequences of delayed diagnosis?

Brittany Partain: Identifying lupus is notoriously difficult due to its highly variable and often nonspecific presentation. Symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, skin rashes, and organ involvement can resemble many other conditions, and they often appear gradually or fluctuate over time. Diagnosis is further complicated by the lack of a single definitive test. While autoantibody tests like ANA are commonly used, they are not specific to lupus and others like anti-dsDNA may be negative in some patients. On average, it takes 4 to 6 years from symptom onset for patients to receive a formal diagnosis, often after seeing multiple specialists or being misdiagnosed. This delay can lead to irreversible organ damage, increased disease activity, more hospitalizations, and a higher burden on patients’ quality of life, both physically and emotionally.

CLP: What is the current gold standard for lupus diagnostic testing? What are its limitations?

Partain: The gold standard for lupus diagnostic testing typically starts with antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing, followed by more specific autoantibodies such as anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith, as well as complement levels (C3 and C4). While ANA is highly sensitive (meaning nearly all patients with SLE will test positive), it lacks specificity and can be positive in a range of other conditions, or even in healthy individuals. In contrast, anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, and low C3/C4 are highly specific for SLE and rarely seen outside the disease. However, these markers are only present in a subset of patients. As a result, many individuals with lupus may go undetected by conventional serologic testing simply because they don’t produce these specific biomarkers.

CLP: In a recent study, it was found that TC4d was effective in identifying up to 24% of lupus patients not detected by the gold standard biomarkers. Why is this biomarker so effective?

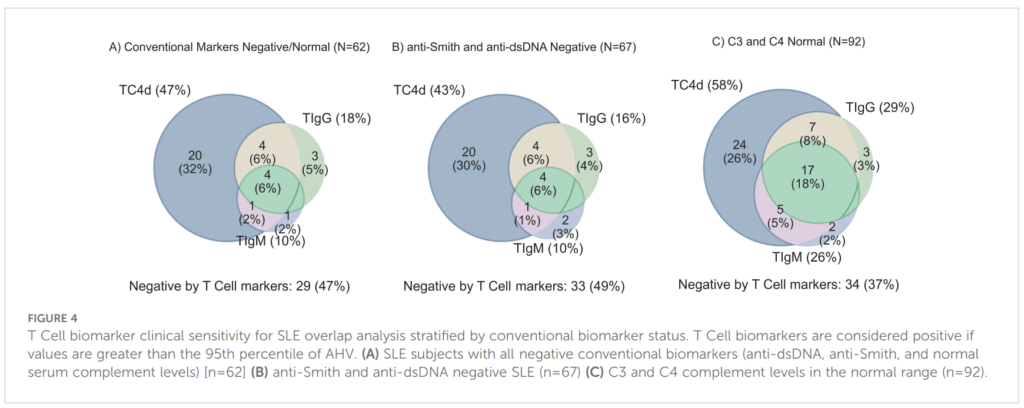

Partain: When you look at the data, specifically Figure 4A (below–Editor) from a recent study in Frontiers in Immunology, you’ll see that TC4d identifies an additional 47% of patients who are negative for the gold standard biomarkers, and it’s independently positive in 32% of patients who test negative for the T Cell autoantibodies. This biomarker is particularly effective because it measures classical complement activation in a more stable and robust way. Unlike C3 and C4 levels, which can fluctuate due to changes in liver production or acute-phase responses, TC4d captures a byproduct of C4, namely C4d, that’s generated specifically during classical complement activation. C4d binds to T Cells and remains on their surface for the lifespan of those cells. In that sense, the relationship between TC4d and complement C3/C4 is similar to the relationship between hemoglobin A1C and fasting glucose, as it provides a longer-term, more stable marker of underlying immune activity.

CLP: Combining this biomarker with traditional testing methods seems to have supercharged its effectiveness at identifying patients with lupus—is this going to lead to a more effective test?

Partain: Absolutely! That’s exactly the value we’re seeing. The T Cell biomarkers, especially TC4d, complement traditional testing by identifying patients who are often missed by standard markers like anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, or low complement. When you combine the novel T Cell biomarkers with traditional testing, you’re not just increasing sensitivity, you’re expanding the clinical reach of testing to patients who otherwise wouldn’t meet the conventional serologic criteria. So, yes, combining these markers creates a more effective and actionable test by filling a key diagnostic gap. It’s not about replacing traditional biomarkers. It’s about building on them to better reflect the diverse immune pathways involved in lupus.

CLP: What’s next? Do you have a test on the horizon?

Partain: We’re currently developing a urinary biomarker panel in collaboration with Johns Hopkins to support treatment decisions in lupus nephritis by predicting inadequate treatment responses. This is a critical area of need because up to 50% of lupus patients develop lupus nephritis, and among those, 60% to 70% fail to achieve complete renal response. Additionally, up to 10% of patients with lupus nephritis progress to end-stage renal disease, requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Featured Image: Natal’ya Buzuevskaya | Dreamstime.com

Chris Wolski is chief editor of CLP.

Reference

- “Lupus Facts and Statistics.” Lupus Foundation of America. 2025. https://www.lupus.org/resources/lupus-facts-and-statistics#:~:text=How%20common%20is%20lupus%20and,and%20teenagers%20develop%20lupus%2C%20too.