Scientists have repurposed the genetic modification technology CRISPR to identify antibodies in patient blood samples in a move that could inspire a new class of medical diagnostics in addition to a host of other applications.

The technology involves customizable collections of proteins which are attached to a variant of Cas9, the protein at the heart of CRISPR, that will bind to DNA but not cut it as it would when used for genetic modification. When these Cas9-fused proteins are applied to a microchip sporting thousands of unique DNA molecules, each protein within the mixture will self-assemble to the position on the chip containing its corresponding DNA sequence. The researchers have called this technique ‘PICASSO’, short for peptide immobilization by Cas9-mediated self-organization. By then applying a blood sample to the PICASSO microarray, the proteins on the microchip that are recognized by patient antibodies can be identified.

The team led by Stephen Elledge, PhD, at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, has published the research online in Molecular Cell. The paper’s first author, Karl Barber, PhD, is a 2018 Schmidt Science Fellow, with much of the work to develop the technology taking place during his Fellowship Research Placement in corresponding author Elledge’s laboratory.

Describing PICASSO, Barber says: “Imagine you want to paint a picture on a canvas, but instead of painting in a normal fashion, you mix all of your paints together, splash it on the canvas, and the perfect picture emerges. With our new technique, you place DNA molecules at defined locations on a surface and each protein from a mixture will then self-assemble to its corresponding DNA sequence, like an automated paint-by-number kit. The resulting DNA-templated protein microarrays allow you to quickly identify antibodies in clinical samples that recognize whatever proteins you are interested in.”

The research team has demonstrated that the technology works to assemble thousands of different proteins, suggesting that it could be readily adapted as a broad-spectrum medical diagnostic tool. In the paper, they used the technique to detect antibodies binding to proteins derived from pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, from the blood of recovering COVID-19 patients.

Barber adds: “In this work, we demonstrated the application of PICASSO for protein studies, creating a tool that we believe could be quickly adapted for medical diagnostics. Our protein self-assembly technique could also be harnessed for the development of new biomaterials and biosensors just by attaching DNA targets to a scaffold and allowing Cas9-linked proteins to bind.”

Group Leader, Elledge, comments: “One of the most exciting aspects of this work is the demonstration of how CRISPR can be applied in an entirely new setting. Previously, CRISPR has been used primarily for gene editing and the detection of DNA or RNA. PICASSO brings the power of CRISPR into a new realm of protein studies, and the molecular self-assembly strategy we show may assist in developing new research and diagnostic tools.”

Megan Kenna, DPhil, PhD, executive director of Schmidt Science Fellows, said: “This technology has the potential to be used as a medical diagnostic tool that could, one day, provide doctors with a way to quickly determine the diagnosis and best course of treatment for each individual patient.”

The research was supported by Schmidt Science Fellows, the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research, National Science Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

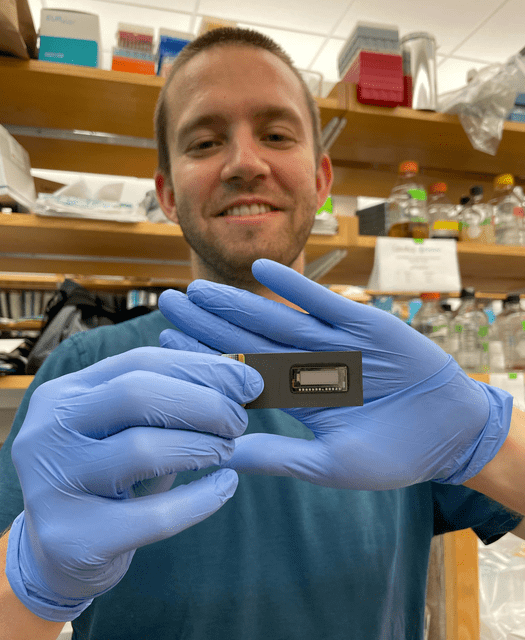

Featured Image: Lead author, Karl Barber with a PICASSO microarray. Photo: Karl Barber, Schmidt Science Fellows