New diagnostic chip pulls packets released from tumor cells out of blood, showing whether cancer cells died during chemotherapy infusion.

Researchers at Northwestern Medicine and the University of Michigan have developed a blood-based test that can determine whether chemotherapy is working for glioblastoma patients after just one treatment dose, potentially eliminating months of waiting for treatment response assessment.

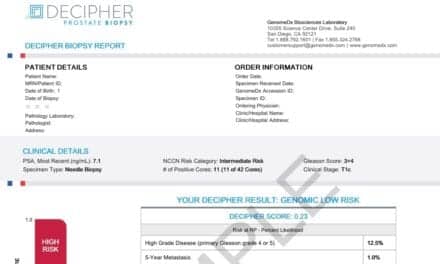

The test, which uses the GlioExoChip technology to detect extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) released by cancer cells, works in conjunction with therapeutic ultrasound that temporarily opens the blood-brain barrier to allow chemotherapy drugs to reach brain tumors. The study was published in Nature Communications.

“Instead of waiting months, after one dose we can know if a given treatment is working,” says Adam Sonaband, neurosurgeon at Northwestern Medicine and co-corresponding author of the study, in a release. “That is huge for glioblastoma patients. It could potentially prevent patients from getting prolonged treatments that are ineffective, thus also avoiding unnecessary side effects.”

Overcoming Blood-Brain Barrier Limitations

Glioblastoma represents one of the most challenging cancers to treat, with most patients dying within two years and only 10% surviving five years. The blood-brain barrier, which protects the brain from toxins, also prevents most chemotherapy agents from reaching brain tumors effectively.

The Northwestern Medicine team conducted a clinical trial using the SonoCloud-9 therapeutic ultrasound device from Carthera, which opens the blood-brain barrier for approximately one hour to allow the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel to penetrate brain tissue. The new diagnostic approach leverages this same barrier opening to allow tumor content to leak into the bloodstream, where it can be detected and analyzed.

“There are tiny particles floating in patient blood, called extracellular vesicles, that have been released by the cancer cells. These particles act as messengers, carrying special bits of genetic tumor material and proteins. The big challenge is figuring out how to find and pull out only those that come from cancer cells and not from elsewhere in the body,” says Sunitha Nagrath, professor of chemical engineering at the University of Michigan and co-corresponding author of the study, in a release.

Technology Captures Cancer-Specific Particles

The Michigan team developed a method to capture EVPs from cancer cells using a specific lipid molecule commonly found on the exosome’s surface. The GlioExoChip processes blood plasma samples to isolate these cancer-derived particles, effectively creating liquid biopsies from standard blood draws.

EVPs from cells that die during treatment become easier to capture because the targeting lipid becomes more abundant on dying cells. Researchers count the extracellular vesicles before and after each treatment, calculating a ratio by dividing the post-chemotherapy count by the pre-chemotherapy count. Rising ratios with each chemotherapy session indicate successful treatment, while flat or declining ratios suggest treatment failure.

“Opening the blood-brain barrier allows tumor-derived vesicles to be measured in blood, providing a clinically meaningful liquid biopsy signal,” says Mark Youngblood, MD, neurosurgery resident at Northwestern Medicine and co-first author of the study, in a release. “The GlioExoChip provides a quick and minimally invasive way to monitor treatment response in a disease where MRI scans often give misleading results.”

Future Applications and Commercialization

The research team plans to validate their findings with other glioblastoma therapies and explore the technology’s usefulness for monitoring treatments of other cancers. The team has applied for patent protection through University of Michigan Innovation Partnerships and is seeking commercial partners to bring the technology to market.

The study received primary funding from the National Institutes of Health, with additional support from the Lou and Jean Malnati Brain Tumor Institute, Moceri Family Foundation, University of Michigan Forbes Institute for Cancer Discovery, US Department of Defense, American Brain Tumor Association, Tap Cancer Out, and Focused Ultrasound Foundation.

ID 134824139 © motortion | Dreamstime.com