Blood-based biomarker tests increase accessibility and affordability, putting earlier detection and treatment within reach.

By Nicole Schlosser

Summary:

Blood-based biomarker tests are revolutionizing the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease by enabling earlier, faster, and more accessible detection—helping overcome long-standing diagnostic delays, underdiagnosis, and resource constraints.

Takeaways:

- Blood-based biomarker tests like pTau217 offer a less invasive, faster, and more scalable alternative to PET scans and spinal taps for Alzheimer’s diagnosis, with comparable accuracy.

- Underdiagnosis remains a major challenge, particularly in early stages like mild cognitive impairment (MCI), due to limited specialist access, physician training gaps, and lingering stigma.

- Innovation is accelerating, with multiple companies developing highly sensitive assays, FDA approvals emerging, and trials underway for preventive treatment using these diagnostics as a clinical gateway.

Nearly 500,000 Americans will receive a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s in 2025, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, adding to the more than 7 million people in the U.S. aged 65 and older who are already living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is expected to double by 2050.

Even with these seemingly high numbers dementia is often underdiagnosed. Underdiagnosis occurs mainly in the early stages of dementia, and a recent study estimates that only 8% of older Americans living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) receive a diagnosis.

Two proteins, amyloid and tau, are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s. As these proteins accumulate in neurofibrillary tangles and form plaque in the brain, they disrupt signals from neurons to different parts of the brain, causing cognitive decline. Michael Racke, MD, medical director for neurology at Quest Diagnostics, says that as recently as the 1980s, the telltale plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s could only be detected postmortem, and since there was no treatment, diagnosing the disease wasn’t as critical at the time. Now, tests can detect the disease while the patient is alive, offering a chance at diagnosis and treatment.

Alzheimer’s Diagnostic Testing Evolves

There have been great strides in diagnosing Alzheimer’s since the early 2000s, especially over the last five years, with the advent of blood-based biomarker tests. These tests were spurred by the discovery in 2020 of pTau217, which is detectable in the blood, according to the scientific journal Nature.

The diagnostic process evolved from postmortem exams to invasive imaging scans using positron emission tomography (PET), using a tracer to make amyloid and tau deposits in the brain visible, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker ratio assays, which can detect early changes in the amyloid and tau proteins in spinal fluid, collected via a lumbar puncture.

PET imaging and CSF assays present limitations, due to access, invasiveness, and expense. In contrast, blood-based biomarker tests offer a less costly, minimally invasive diagnostic tool that is more scalable and also more accessible for a broader population.

Blood-based tests also save time. If a patient is assessed for cognitive impairment and their doctor wants to check whether they have the pathology consistent with Alzheimer’s, instead of having to wait several weeks for a PET scan, they can send the patient to the lab for a blood test, get the answer within a week, diagnose the patient, and begin treatment.

Moreover, the tests will help patients struggling with a dearth of healthcare resources, another barrier to quickly and correctly diagnosing Alzheimer’s.

“There are not enough primary care physicians currently,” Maria-Magdalena Patru, MD, PhD, scientific partner at Roche Diagnostics, says. “The existing ones have insufficient dementia training and face significant time constraints, making it difficult to detect patients with cognitive impairment in a timely manner.”

When those patients can be identified, there is a long wait to see a specialist, because there are not enough to meet the demand. Russ Lebovitz, CEO of biotech company Amprion, adds that a visit to a specialist can involve multiple clinical tests, costing tens of thousands of dollars.

“Our test [costs] significantly less than that, and you can get a definitive answer in the first visit,” Lebovitz says. “It takes a lot of the load off of physicians, who already are overloaded, and it will reduce the overall cost of multiple, expensive visits.”

Patru stresses that the laboratory’s role of adopting biomarkers to increase patient access is critical, but needs to be bolstered by increasing healthcare resources and coverage of biomarker tests and therapies.

Diagnostic Challenges

Despite the breakthrough of blood-based biomarker testing, several diagnostic obstacles remain.

One hurdle in validating diagnostic and drug testing is selecting cohorts that reflect the diversity in the general population, says Robert Martone, scientific discipline director of neurology biomarkers for Labcorp.

He adds that identifying a patient’s dementia type can be challenging for doctors, which is why Labcorp is developing blood-based tests for a wide range of neurodegenerative diseases outside of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomarker tests enable selection of the appropriate subjects for clinical trials and patients to undergo treatment, Martone says. Patru also cites the challenge of association of AD with other pathologies, atypical presentations of AD, and of diagnosing AD in its early disease stage (i.e. MCI, mild dementia).

“It is very challenging for clinicians to accurately diagnose Alzheimer’s, especially in the early stages,” she says. “Until the availability of biomarkers, it has been done by ruling out other potential causes of cognitive impairment.”

The disease can present with co-pathologies, especially in older patients, or look like other dementias, such as Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia, which can further complicate making a diagnosis, and requires a panel of biomarkers. pTau181 and pTau217 occur in other neurodegenerative disorders, like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, but are found more frequently in Alzheimer’s disease, Racke says. A blood-based biomarker test on a patient who appears to have frontotemporal dementia may also look like Alzheimer’s, because positive amyloid and tau occur in both instances.

Alzheimer’s that is located in the frontal and temporal lobes may look more like frontotemporal dementia, since it isn’t in the more typically located parietal and frontal lobes.

“It’s like [the saying], ‘What are the three most important things in real estate? Location, location, location?’ That’s true in neurology as well,” Racke says.

Additionally, there is a stigma attached to the diagnosis and an assumption that nothing can be done, causing patients anxiety and to misattribute symptoms, like forgetfulness, to their age, and avoid discussing them with a doctor.

Patru mentions that learning about the availability of the biomarker tests which can help clinical diagnosis and the amyloid targeting therapies shown to slow cognitive decline in symptomatic individuals, can help lessen patients’ fears about seeking a diagnosis. This underlines the importance of awareness and education efforts that need to be conducted.

Another complicating factor, Racke says, is that people accumulate amyloid about 20 years before they become symptomatic. Not knowing when the accumulation started leaves doctors hesitant to tell patients who are amyloid positive that they’re at risk of potentially developing Alzheimer’s in a couple of decades.

Moreover, the tests should always be considered within the full clinical picture of the patient. That includes a cognitive assessment, and doctors may need a CSF assay or PET scan for confirmation in some instances, such as patients with mild elevations of biomarkers or some co-pathologies.

“We are excited about the positive impact of AD blood-based biomarkers, but we cannot dismiss confirmatory tests such as CSF or PET, because they will still be needed for some patients,” Patru says.

A Golden Age for Testing Innovations

The blood-based biomarker test breakthrough can make it easier to diagnose patients, decide who to enroll in trials, and more easily evaluate the response to therapy in trials. Driving this progress is rapid growth in therapeutic innovations and technological improvements enabling ultra-sensitive immunoassays, Martone adds.

Use of well-characterized biomarkers, like pTau217, pTau181, and amyloid beta 42/40, lagged because of a lack of treatment. Before drugs that treat mild cognitive impairment, like leqembi and donanemab, were on the market, many doctors questioned whether they should diagnose a patient with Alzheimer’s if there was no treatment available. Now, many are more willing to make a diagnosis. It is important to note, Racke adds, that anti-amyloid therapies slow down decline, but don’t improve cognitive function.

“It’s a really exciting time, because the pace of innovation in the field is unprecedented,” Martone says. “Labcorp is committed to driving that momentum because it is creating meaningful progress for patients, and helping people in their clinical pathway.”

Mike Miller, COO of biotech company Quanterix, adds that among several new biomarker discoveries fueling diagnostics innovation is Neurofilament Light (NfL), a marker of neurodegeneration that has been used for accelerated approval of some drugs treating ALS.

“It’s an iterative process; improvements in therapeutics drive improvements in biomarkers, and vice versa,” Martone notes.

Boosting Sensitivity for Earlier Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

In addition to identifying amyloid, tau, and other biomarkers, companies are increasing sensitivity and specificity levels in their tests, making accuracy comparable to PET and CSF tests, to help physicians assess patients’ probability level of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Guidelines from CEOI, The Global CEO, initiative for Alzheimer’s disease, recommend that blood-based biomarkers have 90% sensitivity and specificity with 90% negative and positive predictive value if the cohort has 50% PET prevalence.

- Companies that offer tests with 90%+ high sensitivity include ALZpath, Amprion, Fujirebio Diagnostics, Labcorp, Quanterix, and Quest Diagnostics.

- Tests that provide a likelihood score include ALZpath’s pTau217 antibody, which mainly identifies patients as either high or low probability for a potential Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Patients with a high probability result receive a recommendation of CSF testing or PET imaging; and Quest Diagnostics’ recently launched panel, AD Detect Abeta 42/40 and p-tau217 Evaluation, which uses in vitro immunoassay results are used to produce an AD-Detect Likelihood Score.

- Also worth noting is one test that recently received U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approval: Fujirebio Diagnostics’ Lumipulse G pTau217/ß-Amyloid 1-42 Plasma Ratio, the first blood biomarker test to assist in diagnosing Alzheimer’s.

- Roche Diagnostics Elecsys pTau217 and pTau181 assays have received Breakthrough Device Designation and are currently in development.

Next Steps

While relatively new, it is likely that the use of blood-based biomarkers in neuroscience will continue to grow, and will gradually play a larger role in disease prevention.

Quanterix’s Miller says that pharmaceutical companies are holding trials to test treating presymptomatic patients to prevent cognitive decline, and high-sensitivity blood biomarker tests may make that easier. If those trials prove successful in preventing or even helping delay symptoms, doctors may eventually use the tests to determine whether patients may be a candidate for therapy, for example, as part of a routine physical for people who are over 60.

“In the spirit of innovation which characterizes Roche, we are focused on finding new biomarkers involved in other pathologies with roles in AD,” Patru says. “[There’s] a lot of work with the patient in mind, and figuring out how to prevent this cognitive decline cascade, giving time, and giving ‘brain’ to these patients, because in Alzheimer’s, time is brain. That lessens the burden…because Alzheimer’s is a very impactful disease, not just for the family and the patient, but for both society and the healthcare system.”

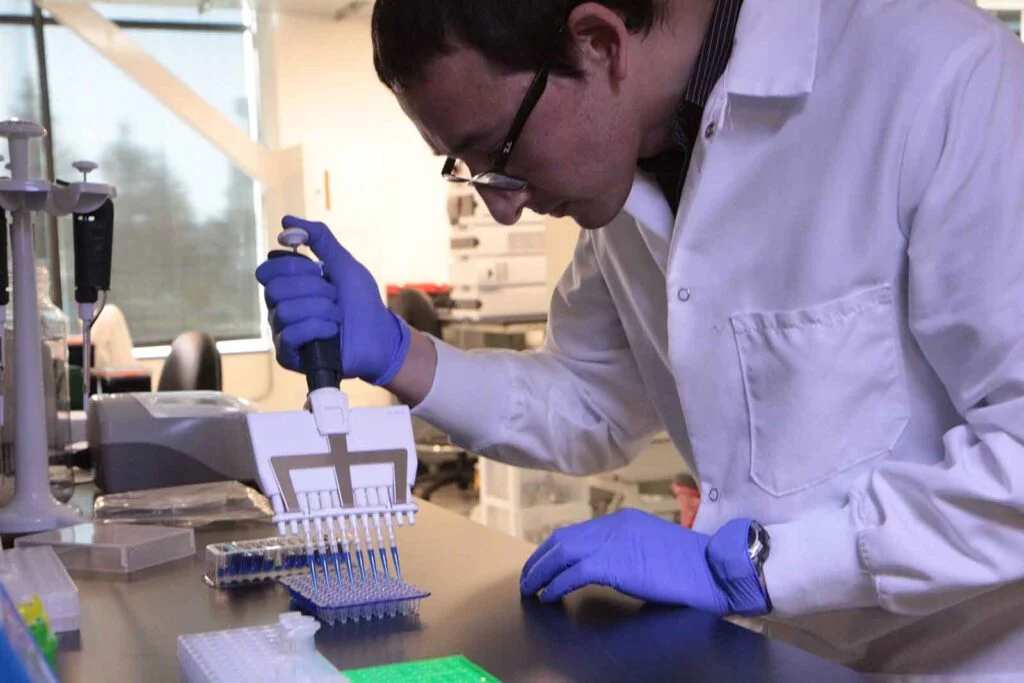

Featured Image: Blood-based Alzheimer’s testing are less invasive, expensive, and time consuming than traditional PET and CSF testing. This allows treatment to begin sooner–helping to slow progression of the disease. Image: Quest Diagnostics

Southern California-based freelance writer Nicole Schlosser is a contributing writer to CLP.