Summary:

The vaginal microbiome is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that varies across populations, yet research is limited by geographical disparities; international collaboration, such as the Isala Sisterhood, aims to close these knowledge gaps and improve women’s health worldwide.

Takeaways:

- Traditional classifications of vaginal microbiotas may be too simplistic, as over 10% of Belgian participants fell outside standard categories.

- A reduction in lactobacilli is linked to various health conditions, including bacterial vaginosis, which has limited treatment success with antibiotics.

- Cultural and social factors, like hygiene practices, influence vaginal microbiomes, highlighting the need for diverse, global research collaborations.

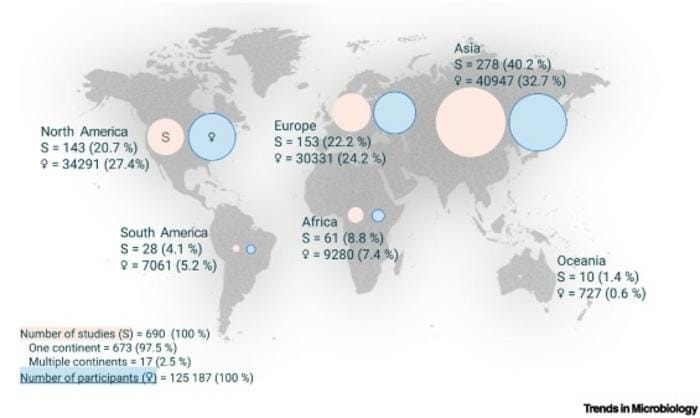

Vaginas host a complex microcosm of bacteria and yeasts that can fluctuate over time. However, little is known about these microbial communities and their roles in a person’s health, and 9 out of 10 studies only include participants from one continent, resulting in major geographical gaps in data. In a paper published in the Cell Press journal Trends in Microbiology, scientists share insights gleaned from a “sisterhood” of thousands of citizen scientists and demonstrate how international collaboration can help illuminate the gaps in our knowledge about the vaginal microbiome, including which bacteria are helpful or harmful and whether microbiomes look different for people across the globe.

“Women’s health is essential to global societal and economic wellbeing, yet health disparities remain prevalent,” write the researchers, comprised of scientists from 4 continents and 9 countries, including lead author Sarah Lebeer of the University of Antwerp in Belgium. “Women’s bodies, and knowledge concerning their health have been neglected, controlled, and persecuted for centuries, resulting in a health disparity that persists today.”

Isala Sisterhood Consists of Coalition of Scientists Aiming to Research Women’s Health

The authors are involved in citizen science initiatives called the Isala Sisterhood, which aim to inspire research on women’s health and microbiomes worldwide by creating a reference map of vaginal microbiota. Originally launched in Belgium as the Isala Project with over 6,000 participants, the Isala Project has grown into a “sisterhood” including microbiologists, health care workers, governmental organizations, and the public, and branched out across North America, South America, Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Isala Sisterhood Has Almost 100 Years of Vaginal Microbiome Research

Lebeer and her team compiled insights from the Isala Sisterhood and other similar initiatives alongside almost 100 years of research. Key takeaways include the following:

- There are five different categories of “healthy” vaginal microbiotas commonly used in the field, described based on the vagina’s most dominant bacterial species. These include Lactobacillus crispatus-dominant, Lactobacillus gasseri-dominant, Lactobacillus iners-dominant, Lactobacillus jensenii-dominant, and a fifth category that includes a mixture of other species. However, the Isala Project has found that within the Belgian population, over 10% of participants fall outside of these categories. Therefore, the project recommends “considering the whole complexity and continuity of the vaginal microbiota composition and functionality” instead of relying on the categories.

- Several studies have found associations between the makeup of the vaginal microbiota and clinical conditions. One of the most well-researched is the impact of a reduction in lactobacilli, which often results in an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, potentially leading to health impacts including preterm birth, urinary tract infections, endometritis, and sexually transmitted infections.

- A common condition caused by a reduction in lactobacilli is bacterial vaginosis which is typically treated using targeted antibiotics with limited efficacy—up to 60% of the time, symptoms resurface. Vaginal live biotherapeutic products, FDA-approved treatments that use live microorganisms, may be more effective in treating or preventing these and other vagina-related health conditions than existing treatment options.

- Some studies suggest that certain cultural hygiene behaviors such as vaginal douching can contribute to a higher risk of conditions such as vaginal dysbiosis. The authors note that examples such as this show that differences in the vaginal microbiome—and the health disparities they might correspond to—can be attributed to both biological and social factors.

- Several other types of microbes exist in vaginal microbiomes, including yeasts, viruses, and other types of bacteria. However, the roles they play in the microbiota and a person’s health are largely unexplored.

- In general, lower- and middle-income countries are underrepresented in microbiome research. The authors note that infrastructure, technology, and finances likely contribute to these disparities and recommend leveraging international collaborations that share resources ranging from lab materials to communications techniques in an effort to overcome these challenges.

- Initiatives like the Isala Project and its sisterhood—including the Vaginal Human Microbiome project, which is working to map the vaginal microbiomes of people from different ethnic backgrounds across the United States—aimed at “closing the vaginal microbiome data gap” are growing in number across the world.

Vaginal Microbiome Has Connection to Overall Health

The authors emphasize the importance of continuing to study the vaginal microbiome and its connection to a person’s overall health through studies that focus on geographical and socioeconomic diversity and consider social and cultural factors.

“To promote better preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies for women affected by conditions associated with the vaginal microbiota, more research on the functions and diversity of the vaginal microbiota is urgently needed in different parts of the world,” write the authors. “This way, we can better understand what a healthy vaginal microbiome looks like in each geographical location.”

Featured Image: World distribution of the vaginal microbiome data studies using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Image: Trends in Microbiology, Lebeer et al.