Since 1949, lithium has been a mainstay for treating bipolar disorder (BD), a mental health condition marked by extreme mood swings. However, scientists still don’t have a clear understanding of how the drug works or why some patients respond better than others.

To explore this area of study, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, have developed a method for imaging lithium in living cells, allowing them to discover that neurons from BD patients accumulate higher levels of lithium than healthy controls. Their findings appear in ACS Central Science.

According to the National Institutes of Health, 4.4% of U.S. adults experience bipolar disorder at some time in their lives. Studies have shown that lithium-based drugs can help stabilize mood and reduce suicide risk in people with BD. However, only about one-third of BD patients respond completely to lithium treatment, and the rest respond only partially or not at all. One reason could be that the drug has an extremely narrow therapeutic range: Below a certain blood serum level of lithium, most patients do not respond, but, at a slightly higher level, they can experience severe side effects.

Being able to measure lithium concentrations directly in a patient’s neurons could help scientists understand how lithium works as a drug, and then they could use this knowledge to optimize the dosage. Yi Lu, PhD, then a chemistry professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and colleagues wanted to develop a method to detect and measure lithium in living cells at therapeutically relevant concentrations.

The researchers used in vitro selection to identify a DNA enzyme (DNAzyme) that catalyzes the release of a fluorescent molecule from an RNA probe, thus producing a signal, only when lithium is present. The DNAzyme was 100 times more selective for lithium over other metal ions, such as sodium and potassium, that are present at much higher concentrations in human cells, and it was sensitive enough to detect lithium at concentrations within the therapeutic range.

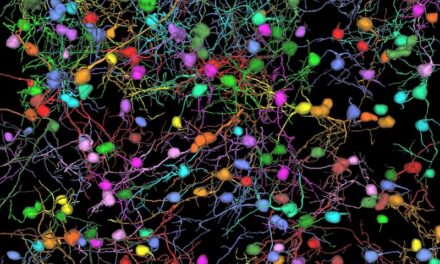

As a proof of concept, the researchers collected skin cells from BD patients and healthy donors, reprogrammed them to stem cells, and then differentiated them into neurons. The team treated the neurons with the DNAzyme-based sensor and a therapeutically relevant dosage of lithium. Using fluorescence microscopy, the researchers found that immature neurons from BD patients and healthy controls accumulated similar levels of lithium, but mature neurons from BD patients accumulated higher levels of lithium than mature control neurons. The new lithium sensor is a powerful tool to better understand the effects of lithium in treating BD, the researchers say.