SWHR campaign boosts impact of molecular diagnostics on women’s health

Interview by Steve Halasey

In April of this year, the Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR) launched a yearlong public awareness campaign on the importance of molecular diagnostics for protecting and improving the health of women.

The campaign was announced during the society’s annual gala event, with a film highlighting the powerful impact of molecular diagnostics on women’s health—including coronary artery disease, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, sexually transmitted diseases, and mental health. The film is expected to be the cornerstone of a national multimedia campaign that will include print, TV, and radio public service announcements that highlight the benefits of molecular diagnostics for everyday women.

This September, the society will press onward with its efforts, hosting a breakfast and panel discussion on molecular diagnostics at the annual TedMed conference in Washington, DC. The TedMed conference brings together leading innovators and investors from the global community who share an interest in science, medicine, and research. SWHR’s panel of nationally recognized experts—including Eric D. Green, MD, PhD, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute—will discuss various topics related to molecular diagnostics, including the history of the field, current and future innovations, and the value of molecular diagnostics in medicine and healthcare.

To find out more about the public awareness campaign and its aspirations, CLP spoke with Phyllis Greenberger, SWHR president and CEO.

CLP: SWHR supports research and education about women’s health, including the biological differences between men and women in health and disease. Why has the organization undertaken a public awareness campaign focused on molecular diagnostics?

Phyllis Greenberger: I have been thinking about this area for a number of years, and learning more and more about it. But now there seems to be so much going on—more than there ever has been in the past—and a lot of it has to do with women’s health. Since we often use diagnostics to focus in on sex differences in health and disease—and specifically to understand how a lot of conditions affect women—using genomics to understand these issues is very consistent with our mission in women’s health.

CLP: Have there been particular discoveries or technological advances in this field that make now the right time for such a campaign?

Greenberger: In the past, news about advances in the field tended to dribble out slowly, a little here, and a little there. But now, there just seems to be a flood of innovation, and we have companies and people talking to us about various diagnostics all the time. There are two types of applications that we focus on. The first is obviously tests used in diagnosis, trying to figure out early whether a person has a particular disease. The second is tests that can be used to determine what the best treatment is for a given individual.

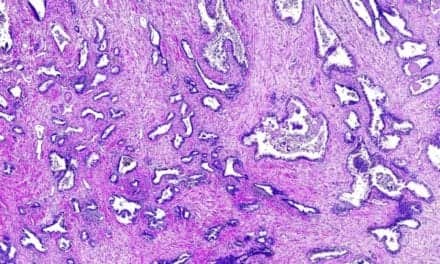

Diagnostics for ovarian cancer offer a perfect example of the second application. For a number of women with ovarian cancer, finding the right treatment seems like something of a guessing game. A variety of different treatments may be tried. If one fails, they try another; and if that one doesn’t work, still another. But now, one company has a diagnostic that can help to determine what therapy is going to work for a particular individual—and that’s an amazing advance.

CLP: Do molecular diagnostics offer an especially focused pathway for understanding women’s health and disease—including cancers that affect women?

Greenberger: We probably use the term “molecular diagnostics” a little bit inappropriately to represent the general concept of precision medicine or personalized medicine.

In the long run, these emerging tools may be able to replace some of the other types of diagnostics, such as those involving imaging. We know that mammograms have somewhat high rates of false positives. But if we develop tools with lower false positive rates that can also determine what kind of breast cancer a woman has, those tools will ultimately replace a lot of what we have now.

As we learn more about genetics and can really pinpoint our applications, we probably will be able to diagnose much more quickly and treat more appropriately than we currently do.

One of the very exciting areas that affects both men and women—but women in disproportionately high numbers—isn’t cancer, but mental illness. Women suffer from a number of mental health issues disproportionately from men, and there are a couple of diagnostics that can determine which medications will work best.

Everybody pretty much knows that in this area, there’s a lot of trial and failure. People try different types of antidepressants, and when one doesn’t work they have to keep trying other ones. Having diagnostics that can predict whether a given medication will work saves all the time and money associated with trial and error, and more importantly, it helps people at an earlier point, so that they don’t have to suffer through therapies that might fail.

There are actually a couple of companies working in this area. One that we previewed at our April dinner is working on diagnostics to help determine which therapy to use. Another is focusing on the brain in order to determine the patient’s diagnosis.

CLP: Apart from scientific challenges, advances in molecular diagnostics can also run afoul of other obstacles, such as ethics considerations, insufficient funding for basic and translational research, burdensome regulatory pathways, and insufficient reimbursement coverage. What kinds of obstacles does SWHR consider most important, and why?

Greenberger: I think there are three main obstacles. The first is coverage. There isn’t a company we’ve spoken to or a presentation or briefing I’ve attended when there hasn’t been a plea for greater coverage of diagnostics. The situation is interesting. Last October, FDA released a 60-page report on “Paving the Way for Personalized Medicine,” which in large part lauded the benefits and importance of molecular diagnostics.1 And yet, at the same time, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is just not providing reimbursement for those tests. I think that’s a problem.

A second obstacle, which arises in part because of the difficult regulatory pathways required for molecular diagnostics, is that small companies sometimes have trouble raising investment money. This is penny-wise and pound-foolish. We should recognize that we do have to put money in up front if we expect to get these diagnostics out into use. I assume and believe it is true that if people are treated more appropriately and more quickly in the first instance, then in the long run the healthcare system will save money.

A third obstacle is that even for those diagnostics that have been available on the market, a lot of physicians aren’t aware of them and don’t use them, and many patients don’t know to ask about them. A lot of what we’re focusing on is educating consumers and patients—everybody becomes a patient at some point—so that if they are diagnosed as having breast cancer, or ovarian cancer, or a tumor that might be malignant, they know enough to find a doctor who has this information, can determine their diagnoses quickly, and can identify the treatment that’s going to be most effective.

CLP: From a policy point of view, is the problem of inconsistency among agencies something that is amenable to correction through congressional action? Would there be any benefit if Congress insisted that FDA and CMS pursue a coordinated policy so that this field can move forward?

Greenberger: Congress could do that. But of course, we all know that Congress isn’t doing much of anything right now. And another issue would be funding for any such initiative. The coverage decisions that we’re seeing from both CMS and the third-party insurance carriers are essentially being driven by fear that they won’t be able to afford their commitments because of their obligations under the Affordable Care Act. So there are a lot of issues.

I think there needs to be Congressional action. If Congress really made it clear that it expected CMS to support the development and adoption of molecular diagnostics, I suppose the agency would have to respond. But the private insurance companies have to join in as well. If private carriers refuse to cover molecular diagnostics, or don’t cover them sufficiently to make it worthwhile for physicians to use them, it’s not going to happen.

CLP: The June 2013 US Supreme Court ruling in the Myriad case has opened the doors to competition in areas involving genetic testing—including molecular diagnostics. One result has been some cross-litigation among labs and manufacturers in the field, which seems somewhat counterproductive. Does SWHR advocate for any legislative or regulatory policies to reduce the potential for litigation and keep the field moving forward?

Greenberger: We haven’t gotten into that. There are two sides to that story, and both are interesting. Obviously, if more labs or companies are able to make these tests available, then the price is going to go down, and the tests will be more readily available to patients. On the other hand, you don’t want to stifle innovation, and there needs to be some protection for discovery.

It was exciting when Myriad discovered BRCA testing, and of course, people were willing to pay out of their own pockets, for all the reasons we know about. But we’re not in a position to make that decision. Our position is that these tests should be available and affordable.

Maybe this needs to be handled the way that patents are for pharma companies, with protection available for a finite amount of time, and an open market after that. Because if there’s no patent protection at all, it might keep companies from investing in developing these new diagnostics.

In any case, SWHR is not going to get involved in this one. This is a legal matter, and we don’t want to go there. I do see the value of having some protection. Otherwise, if a product becomes shared with everyone as soon as it comes out, it wouldn’t be worthwhile for a company to put a lot of money into developing it. On the other hand, at a certain point products need to be made widely available, and they’re going to be a lot less expensive if they’re offered by many competing companies instead of just one.

CLP: The SWHR campaign will reach a number of different target audiences, including those in the health policy community. What is the overall message the campaign hopes to communicate?

Greenberger: The key message is really the importance of personalized medicine or molecular diagnostics, however it may be defined. And I think there are three audiences for that.

We’ve had public service announcements, newspaper articles, and media hits all directed toward educating individuals to the fact that these diagnostics exist. We want to make sure that people know about them and ask about them when they see their doctors.

Hopefully, that message is also getting through to some of the physicians. Many companies have told us that physicians sometimes aren’t as informed as they should be about how to use molecular diagnostics to guide therapy. But they can get help. In the case of ovarian cancer, for example, there’s a lab in California that will perform analyses on tumor biopsies to determine what treatment is going to work for that particular patient. This way, patients don’t have to repeatedly go through the “try one and fail” process.

Similarly, for breast cancer, there’s a test that can determine whether chemotherapy is going to be effective against a particular patient’s type of cancer. Right now, everybody receives chemotherapy, because that’s the standard of care. But the reality is that as many as 9 out of 10 women who get chemotherapy don’t really need it. Of course, chemotherapy has a lot of negative effects on the rest of the body, and it may also result in patients developing other conditions at some time in the future. So it would be a major step forward if we were able to eliminate the use of chemotherapy in people who don’t need it.

CLP: The possibility of such collateral damage from chemotherapy extends the notion of healthcare-associated disorders out to whole new disease level.

Greenberger: We’re actually trying to do some research on the after-effects of chemotherapy. If you go to several sessions of chemotherapy, it affects the rest of your body, your brain, and everything. Sometimes the treatments work at the time, but later on result in the development of other conditions.

For instance, there is information showing that some treatments for cardiovascular disease can cause breast cancer, and conversely, that some treatments for breast cancer can cause cardiovascular disease.

Children’s cancers have been very successfully treated. But there’s information coming out to the effect that children who were treated for cancer early on later develop other cancers.

Obviously, avoiding chemotherapy won’t solve every problem, but if you can reduce exposure to unnecessary treatments, that alone is a big step forward.

CLP: Are there specific policy outcomes that SWHR hopes to achieve through its campaign?

Greenberger: The key issue is coverage. We conducted a briefing for congressional staff members on Capitol Hill to acquaint them with all the issues we’re talking about here. Obviously, when such an event takes place on the Hill, it’s intended to get the message through that this is important and that Congress needs to pay attention to it.

We’ll continue with our educational campaign, but our policy emphasis, I think, is going to be focused on coverage. We’re brainstorming about what other things we can do to get CMS to pay attention to this.

But ultimately, we know coverage decisions are all about money. And it looks like that situation is going to get worse. The president wants money to deal with the current immigration crisis, and some in Congress want to take it out of the budget of the Department of Health and Human Services—which means CMS and FDA. If Congress starts cutting the health care budget, that’s going to affect reimbursement for everything.

And then there are the healthcare insurance carriers, who have issues of their own. Molecular diagnostics for patients not covered by Medicare (that is, those with employer-based insurance) might be reimbursed at a higher rate, but private insurers generally take their lead from CMS coverage decisions. Depending on the cost of the equipment and test consumables, if a test is expensive and the reimbursement rate is low, providers may choose not to do the tests.

CLP: What are your personal hopes for advances in the field of molecular diagnostics?

Greenberger: SWHR’s initial mission was to promote the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials. We were responsible for submitting a 1996 proposal to the Institute of Medicine that eventually emerged as policy in 2001, and essentially said that “every cell has a sex,” and that “research into sex differences need to be taken into consideration from womb to tomb.”

Since sex is the basic variable that everything starts with, we are encouraged that more researchers are looking at sex differences. In a May commentary published in Nature, for instance, Francis Collins, director of NIH, and Janine Clayton, director of the institutes’ Office of Research on Women’s Health, announced new NIH policies to ensure that both males and females are included in NIH-funded basic and preclinical research.2 We have been working behind the scenes on that policy, and we’re pleased to see it formalized at last.

Using personalized medicine approaches is really the epitome of looking at sex differences. Obviously, every person is not going to have their own prescription drug or diagnostic. But if we can understand and more quickly use sex as the initial variable, we’ll be better able to grapple with other variables that define our individuality.

And in turn, this will enable us to understand and address the main cause that we’ve been advocating for all these years: that we have to understand sex differences and treat men and women differently.

Steve Halasey is chief editor of CLP.

References

1. Paving the Way for Personalized Medicine: FDA’s Role in a New Era of Medical Product Development (Silver Spring, MD: FDA, 2013).

2. Clayton JA, Collins FS. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature. 2014;509(15 May 2014):282–283; doi: 10.1038/509282a.