American Indian and Alaska Native men are less likely to be screened for prostate cancer compared to other racial/ethnic groups, according to new research from Wake Forest University School of Medicine .

The study appears online in Cancer Causes & Control.

“Our findings highlight a significant healthcare disparity in accessing care,” says Chris Gillette, PhD, associate professor of PA Studies at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and principal investigator of the study.

According to the American Cancer Society, there are more than 34,000 prostate cancer deaths in the U.S. each year, and prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death in men. American Indian and Alaska Native men are less likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer. However, their prostate cancer outcomes are much worse than other racial/ethnic groups, especially for men between the ages of 50-59 years old.

There are two tests that providers can use that might help diagnose prostate cancer. One is a digital rectal exam (DRE), and the other is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Elevated levels of PSA in the bloodstream can be indicative of prostate cancer.

For the study, researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the National Ambulatory Medicare Care Survey (NAMCS) datasets from 2013-2016 and 2018 and the NAMCS Community Health Center (CHC) datasets from 2012–2015. NAMCS is a nationally representative sample of visits to non-federal office-based physician clinics while the CHC samples include outpatient visits to physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners at community health centers including federally qualified health centers and Indian Health Service clinics. In the NAMCS dataset, researchers analyzed 509,737,580 visits over a five-year period of which 232,998 were for American Indian and Alaska Native men.

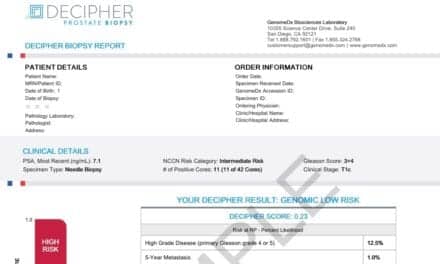

“We found that American Indian and Alaska Native men were significantly less likely to receive a PSA than non-American Indian and Alaska Native men,” Gillette says. “The most alarming finding is that there were zero instances of DREs in the NAMCS dataset over the entire five-year period, and there were no PSAs conducted in American Indian/Alaska Native men after 2014.”

In the NAMCS dataset, the rate of PSAs being ordered for American Indian and Alaska Native men was 1.67 per 100 visits but included no DREs. The rate of PSAs for non-American Indian and Alaska Native men was 9.35 per 100 visits while the prevalence of DRE was 2.52 per 100 visits.

In analyzing the CHC dataset, the researchers noted that American Indian and Alaska Native men had slightly lower rates of PSAs for prostate cancer (4.26 per 100 visits v. 5.00/100) and DREs (0.63 per 100 visits vs. 1.05 per 100) than non-Hispanic White men, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“We found that the disparity may not exist when men visit community health centers,” Gillette says. “More research is needed to better understand why.”

According to Gillette, American Indian and Alaska Native men also experience disproportionately greater prostate cancer mortality compared to other racial/ethnic identities because they present for care when their prostate cancer is more advanced compared to other racial/ethnic groups, which may be a direct result of not getting PSAs and DREs at the same rate as other racial/ethnic groups.

Current screening guidelines recommend that providers use shared decision-making to discuss the benefits and risks of PSA and DRE because current screening tools can lead to false-positive results and the need for more aggressive testing. As men age, the risk of a false-positive result also increases.

Gillette noted because of the way information was compiled for the datasets, it’s impossible to know whether shared decision-making was used when discussing PSA and/or DRE and whether the decision aligned with American Indian and Alaska Native men’s preferences.

“Additional research is needed to explore how providers discuss PSA and DRE with this population, why there are differences in screening practices and to examine access to care,” Gillette says.

Gillette collaborated on the study with the Office of Cancer Health Equity at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist’s NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Featured Image: Chris Gillette, PhD, associate professor of PA Studies at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. Credit: Wake Forest University School of Medicine