Increased levels of certain fats and proteins found in one of the most common forms of dementia — Lewy body dementia — could help with diagnosis and testing for the effectiveness of treatments, according to a new study.

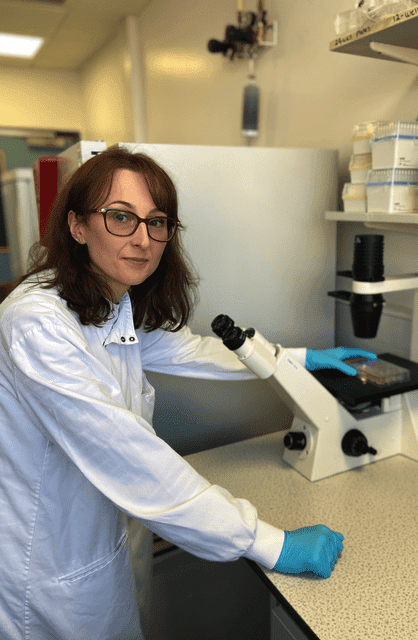

Researchers at Newcastle University led by Marzena Kurzawa-Akanbi, PhD, of the Biosciences Institute have moved a step closer to identifying the cause of Lewy body dementia, with a publication in the journal Acta Neuropathologica.

Lewy body dementia (LBD) affects more than 100,000 people in the U.K. and results in a decline in memory and the ability to concentrate for the person affected. It also causes fluctuating levels of alertness, problems with movement, and visual hallucinations.

“The findings from this study are significant not only as they bring us closer to finding out why nerve cells die in Lewy body dementia, but also, importantly, pave the way towards sensitive and accurate testing for the disease,” Kurzawa-Akanbi says.

Lewy Body Dementia Tied to Gene Changes

A common finding in people with dementia with Lewy bodies is that changes in a gene called glucocerebrosidase (GBA) often occur. It isn’t really understood how changes to GBA lead to LBD, but GBA normally causes the breakdown of certain types of fats in the body, and, particularly, in the brain.

Funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Lewy Body Society, the team in Newcastle and colleague Philip Whitfield, PhD, FRSB, from the University of Glasgow—along with researchers in St. Andrews and Edinburgh in Scotland and Gothenburg in Sweden—investigated how changes in GBA might alter certain fats in Lewy body dementia patients.

The team, which included Ian McKeith, MD, FRCPsych, FMedSci; Chris Morris, PhD; and Mathias Trost, PhD, in Newcastle, found that specific fats called ceramides are increased in brain tissue samples from people who had Lewy body dementia. Surprisingly, the increased amounts of ceramides were found in everyone with Lewy body dementia, and not only in those people who had changes in GBA. This means that these changes in ceramides might be a unique feature of all types of Lewy body disease, which also includes conditions such as Parkinson’s.

The team also found that these ceramide fats were highly increased in small particles called extracellular vesicles (EVs). These EVs are released by all cells, including the damaged and dying cells, and the ones from Lewy body dementia patients also contained an important protein called alpha-synuclein that is implicated in Lewy body disease.

A big problem for people with Lewy body dementia is getting an accurate diagnosis. Putting the two findings of increased ceramides and alpha-synuclein protein together, the team suggests that EVs from LBD patients might in the future be a way to help with diagnosis but also a way to test for effectiveness of treatments.

“This is a very exciting discovery that will give hope to the many thousands of families affected by Lewy body dementia (LBD),” says Jacqueline Cannon, chief executive of the Lewy Body Society. “Since we were founded 15 years ago, our mission as a charity has been to raise awareness of Lewy body dementia and to support research that helps to diagnose and treat the disease.

“Every step forward is very welcome as too often, people living with LBD struggle to get a timely diagnosis, resulting in additional distress for the individual and their family and a delay in receiving appropriate support,” she adds. “Thanks to the generosity of our supporters, we have awarded more than £1.8 million in grants to researchers, and we are fortunate to have some of the global leaders in LBD research here in the UK. We congratulate the team at Newcastle University on the publication of this excellent paper.”

Featured Image: Researchers at Newcastle University led by Marzena Kurzawa-Akanbi, PhD, of the Biosciences Institute have moved a step closer to identifying the cause of LBD, with a publication in the journal Acta Neuropathologica. Photo: Newcastle University, UK