Barrier products are like airbags

BY ELLEN O. LACHANCE, MS, MT(ASCP)SBB

Ellen LaChance, MS, MT(ASCP)SBB, is the manager of the Transfusion and Tissue Service at Eastern Maine Medical Center and Affiliated Laboratory Inc, Bangor, Maine. She is the Transfusion Service technical lead for all transfusion services at the acute care facilities within the Eastern Maine Healthcare System. She wrote this article on behalf of Typenex. |

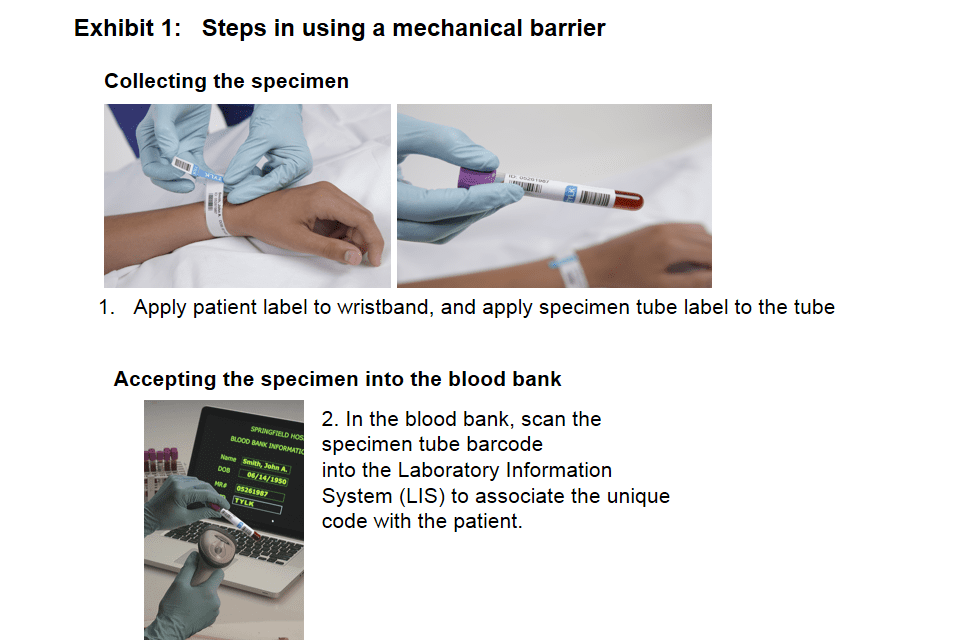

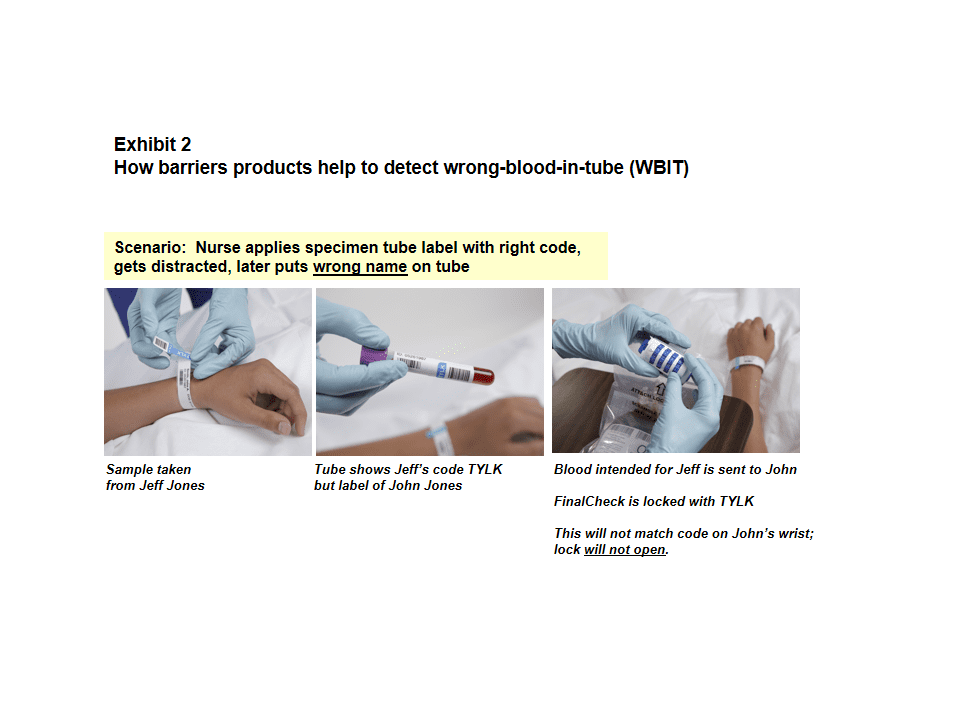

Mechanical barriers are designed to force the patient identity check immediately before a blood transfusion. Barrier products were first developed by two physicians after a mistransfusion led to the death of an elderly patient in New Jersey in 1987. The first barrier product was BloodLoc™ from Novatek Medical Inc, Greenwich, Conn, introduced in the early 1990s. A new-generation version, developed with feedback from BloodLoc users, is called FinalCheck® from Typenex Medical LLC, Chicago.

The mechanical barrier product is simply a lock put on a zip-top overbag that contains the appropriately labeled blood component intended for transfusion. The combination code to the lock is put on the patient’s wristband and on the specimen tube at the time of specimen collection. The code is nowhere else—not in the patient’s charts, posted at nurse’s stations, or on any forms. So, if the locked blood component is taken to the wrong patient, the lock won’t open, as the code on the blood will not match the code on the patient’s wristband. Similarly, if the wrong blood component is taken to a patient, that patient’s wristband code won’t match the one used to lock the unit and the lock will not open.

Mechanical barriers have been cited as preventing transfusion errors in the past1,2, and the experience at Eastern Maine Medical Center, Bangor, Me, described later in this article, adds to that record.

(Click image to enlarge.)

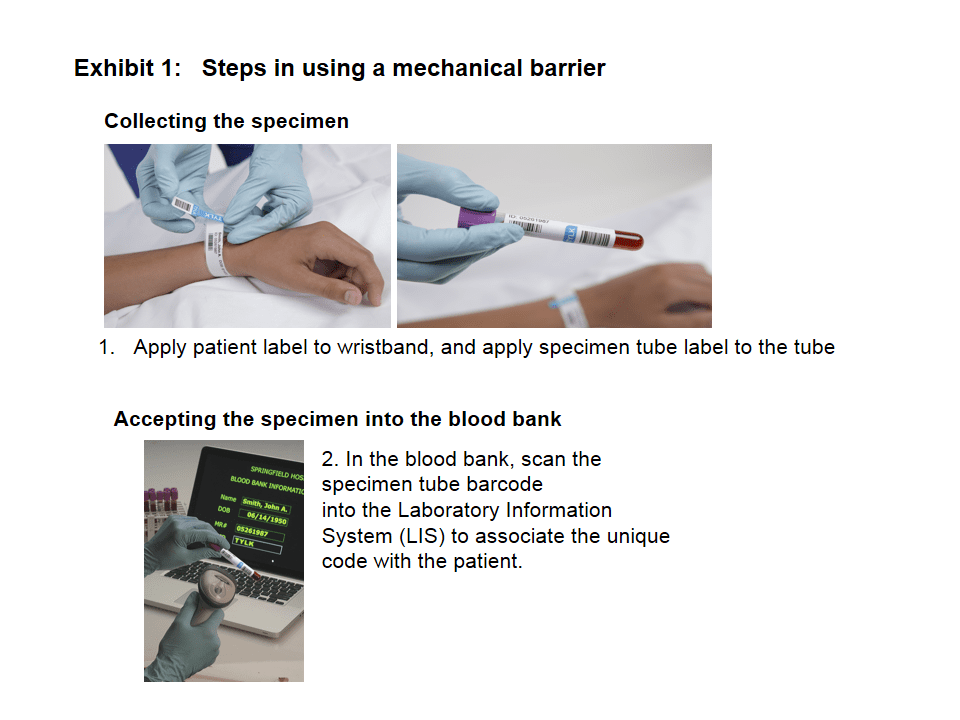

If used properly, barrier products will not only prevent mistransfusions as described above, but they can also address errors during specimen collection. If there is wrong-blood-in-tube (WBIT) and the cross-matched blood is taken to the patient whose (incorrect) name was on the specimen tube, the lock won’t open because the wristband code either won’t be there or will be incorrect.

Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, presented data at the AABB Annual Meeting and CTTXPO 2011 stating that its barrier product detected 24% of WBIT cases over 6 years.3

(Click image to enlarge.)

The growing list of facilities using barrier products includes small community hospitals, regional medical centers, Level I Trauma Centers, military hospitals, and children’s hospitals. Some blood banks lock all components; others lock only red blood cells (RBCs). Most mechanical barrier users agree that it’s critical

to lock components used in all units (medical floors, operating room (OR), emergency department (ED), outpatient infusion/oncology), and not make exceptions; for example, for the trauma area. The locks take a matter of seconds to open, so speed in accessing the blood has not been a significant issue.

(Click image to enlarge.)

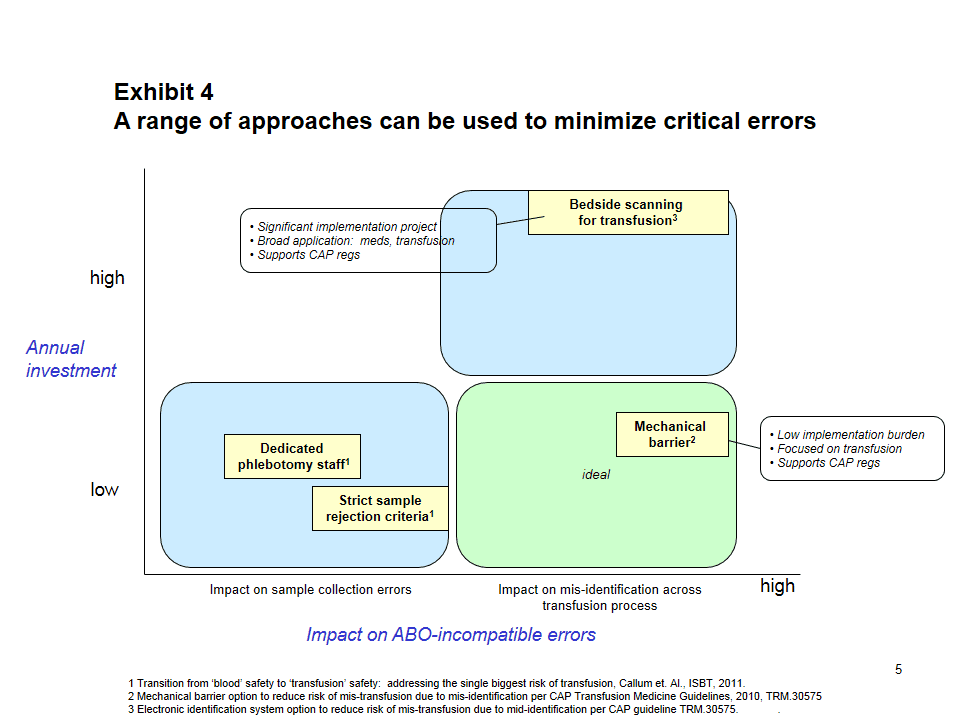

There are, of course, many approaches to assuring that patient identification (ID) is confirmed prior to transfusion, including:

- Two-nurse check of two unique identifiers, often full name and medical record number

- A check of three unique identifiers: in addition to the name and medical record number, a blood bank ID (BBID) from a blood band can be added

- Bedside bar code scanning to confirm patient identity and correct blood component

As with all safety devices and procedures, if all steps are completed with every patient, every time, transfusion safety processes should prevent the misadministration of blood. Unfortunately, many clinical studies have shown that this just doesn’t happen. Some examples from the literature include:

- Three-quarters of 4,046 observed transfusion cases in 233 hospitals lacked completion of one or more of four patient ID steps4

- Six aspects of patient ID pose a significant “opportunity for WBIT”, based on a review of samples from 122 facilities5

- In an analysis of 10 years’ experience of transfusion errors in New York, 40% of ABO-incompatible transfusions were tied to failure at pretransfusion patient ID checks, and 14% to sample collection errors6

- Authors studied bar code medication administration systems (BCMA) use at five hospitals and identified 15 types of workarounds. Nurses overrode BCMA alerts for 4.2% of patients charted.7 It is logical to expect the same risk of workarounds in facilities using bar code scanning at bedside for pretransfusion patient ID checks.

EMMC EXPERIENCE

EMMC is a regional medical center. Its transfusion service issues approximately 550 components per month, with most related to surgery, oncology, and trauma clinical specialties.

Mechanical barriers were evaluated as a way to prevent mistransfusions, especially related to WBIT, as well as to meet the College of American Pathologists (CAP) requirement (TM.30575) to confirm that the pretransfusion specimen was collected from the correct patient. In EMMC’s facility, specimen labels

were not readily available on the nursing units, so there were occasional problems with WBIT when samples were labeled away from the bedside. These problems were detected based on prior blood types on file in blood bank records, or from delta checking of test results from the hematology and chemistry

analyzers.

The blood bank wanted a more direct way to assure WBIT cases were detected every single time. A team of blood bank staff, nurses, and nurse educators evaluated barrier products. After working with the products and trialing them in different areas of the hospital, the team found them to be easy to set and open, yet they created a true barrier that forced the patient ID step. The team concluded that barrier products are a low-cost, high-impact approach to prevent mistransfusions that might arise from errors that could occur in the specimen collection or bedside identification processes.

CAN’T SOMEONE JUST CUT THE BAG TO ACCESS THE BLOOD?

The EMMC team was concerned about the possibility that someone might cut the bag open if they couldn’t open the lock. In discussions with nursing leadership, they all agreed that healthcare workers are humans like everyone else, and will make unintended mistakes when distracted, busy, etc. But an individual’s decision to consciously bypass a safety device would be considered negligence. This mindset was clearly stated and reinforced in all training sessions.

An informal network of mechanical barrier users report using similar strong language at all levels when training staff about barrier products.

REAL RESULTS

It has been more than 6 years since EMMC started using mechanical barriers. They have had zero instances of cutting the bag, and have detected two instances of WBIT that would not have been detected by other methods. Barrier products are like airbags as a safety addition to seatbelts—an extra layer of safety that provides more protection and prevents errors.

|

|

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN MOVING TO A MECHANICAL BARRIER

As with any new process, there are several considerations that must be evaluated to prepare for a smooth implementation:

- Strong culture of safety—from nursing to medical staff and leadership

-Clear language used during implementation to reinforce that it is not okay to bypass a safety device - Procedures needed for both routine process and exceptions, including when:

-Bands are cut off or covered by drapes in the OR

-Lock won’t open

-Blood bank receives a specimen without code

-Massive transfusions - Consider all sources of specimens:

-Inpatients collected by phlebotomy team

-Inpatients collected by nurses

-Patients getting preadmission testing

-Outpatients - Cost

-Consider the cost of obtaining a second sample to verify blood type and compare to the cost of a barrier product. The cost of the barrier product is typically less than $5. The labor cost to collect a second sample is typically more than this.

SUMMARY

There is no perfect system. If every transfusionist did all patient ID steps every time before a transfusion, safety devices, such as barrier devices or bar code scanners, would not be necessary. But we’re human, we get rushed and distracted, and steps get missed unintentionally, leading to errors. Mechanical barriers are a low-cost approach to prevent errors that can occur anywhere in the transfusion process—from the collection of the pretransfusion specimen to the actual transfusion of the blood product.

(Click image to enlarge.)

References:

1. Results of an Integrated Program of Autotransfusion Techniques, Inghilleri, http://www.ztm.si. Accessed 9/19/13.

2. How I Minimize Transfusion Risk in My Hospital, Aubuchon, Transfusion, Vol 46, Jul 2006.

3. Role of a Wristband-Coded Mechanical Barrier System in the Interception of Misidentified Blood Bank Specimens, Garcia-Godos et al, Transfusion, Volume 51, Issue s3, September 2011, Pages: 285A–297A.

4. Audit of Transfusion Procedures in 660 Hospitals (CAP Q-Probes study), Novis et al, Arch Pathol Lab Med, May 2003.

5. Blood Bank Safety Practices; Mislabeled Samples and Wrong Blood in Tube – A Q-Probes Analysis of 122 Clinical Laboratories, Grimm et al, Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2010.

6. Transfusion Errors in New York State: An Analysis of 10 Years’ Experience, Linden et al, Transfusion, Vol 40, Oct 2000.

7. Workarounds to Barcode Medication Administration Systems: Their Occurrences, Causes, and Threats to Patient Safety, Koppel et al, J of American Medical Informatics Association, Jul/Aug 2008.

Ellen LaChance, MS, MT(ASCP)SBB, is a contributing writer for CLP. She is the manager of the Transfusion and Tissue Service at Eastern Maine Medical Center and Affiliated Laboratory Inc, Bangor, Maine. She is the Transfusion Service technical lead for all transfusion services at the acute care facilities within the Eastern Maine Healthcare System. In addition to her work in hospital transfusion services, LaChance has also worked in hospital administration with responsibility for risk management, patient relations, and quality review. She has presented a variety of transfusion-related educational programs at local and regional laboratory and blood bank conferences, and teaches in the CLS program at the University of Maine. LaChance has been a volunteer assessor with the AABB accreditation program since 1982, and has served on the Transfusion Service Accreditation Committee. For more information, contact Editor Judy O’Rourke, [email protected].