High-resolution maps showed us where cells live; the next phase of spatial omics is about extracting those cells and uncovering the molecular conversations that shape outcomes.

By Amos Lee

For the past century, the clinical laboratory has operated on a quest for higher resolution. We moved from the morphological view of hematoxylin and eosin staining, which gave us the “shape” of disease, to immunohistochemistry, which gave us the protein expression of specific cells. Then came the genomic revolution and next-generation sequencing (NGS), which allowed us to sequence the entire library of a tumor’s DNA.

Yet, despite these massive leaps, a critical blind spot remained. Standard bulk sequencing—often described as the “blender method”—takes a complex tissue sample, homogenizes it, and analyzes the average expression of genes. While this tells us what ingredients are present, it destroys the context. We lose the “zip code” of every cell. We might know a patient has high expression of an immune-suppressing gene, but we don’t know if that expression is coming from the tumor itself or the surrounding stroma.

This is where spatial omics has entered the frame, initially hailed as the “Google Maps” of biology. Over the last few years, we have seen an explosion of “atlases”—detailed maps showing exactly where every cell type resides within a tissue architecture. But for the clinical lab director or pathologist, a map is only a starting point. A map shows you the road, but it doesn’t tell you the traffic patterns, the accidents, or the speed limits.

We are now witnessing the next critical phase in this technology’s maturity: the shift from maps to mechanisms. The future of precision medicine in the clinical lab will not just be about locating cells; it will be about the capability to physically isolate and understand the functional conversations happening between them.

The Limits of “Where”: Why High-Resolution Atlases Are Not Enough

The first generation of spatial technologies was defined by “phenotyping”—identifying that Cell A is a B-cell and Cell B is a macrophage, and noting they are next to each other. Current state-of-the-art platforms have achieved breathtaking resolution, allowing us to see down to the subcellular level. We can now visualize RNA transcripts dotting a tissue slide like stars in a night sky.

However, visualization has a ceiling. Simply knowing that an immune cell has infiltrated a tumor is insufficient if we do not know its functional state. Is that T-cell poised to attack, or has it been rendered “exhausted” by the tumor microenvironment? Is the fibroblast next to it secreting collagen to build a protective wall around the cancer, preventing drug delivery?

To answer these questions, we must go deeper than image features. We need to access the “deep” molecular reality—the full transcriptomic and proteomic profile—that lies within those regions. This is where the industry faces its current bottleneck: We have excellent tools for looking (atlasing), but we lack streamlined tools for touching (extraction).

The Dual Role of AI: Pathology vs Omics

As we attempt to bridge the gap between image and mechanism, artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful, yet bifurcated, tool. It is critical for clinical leaders to understand the distinction between AI for pathology and AI for omics, and how they must eventually converge.

AI Pathology: The Scout

AI in digital pathology is rapidly becoming an indispensable “scout.” Algorithms can scan thousands of slides to identify regions of interest—such as areas of high tumor budding, specific inflammatory patterns, or subtle morphological changes that the human eye might miss.

However, if we stop here, we are left with what we might call “shallow omics.” The AI has identified a visual feature, perhaps predicting a mutation based on morphology, but it remains a prediction. It is a correlation, not a validation. The AI can tell us, “This area looks suspicious,” or “This cellular neighborhood resembles a non-responder profile,” but it cannot definitively sequence the unknown mutations or pathway activations driving that appearance.

AI Omics: The Decoder

This is where AI omics comes into play. Once we have the deep molecular data, AI models will be essential to delineate the main differences between the “very important areas” flagged by the pathology AI. These algorithms will move beyond image recognition to pattern recognition in high-dimensional data, linking spatial positioning to gene expression networks.

But there is a missing link between the scout (pathology AI) and the decoder (omics AI). How do we get the physical molecular data from the specific region the Scout found, so the Decoder can analyze it?

The Missing Link: Spatial Selection and Extraction

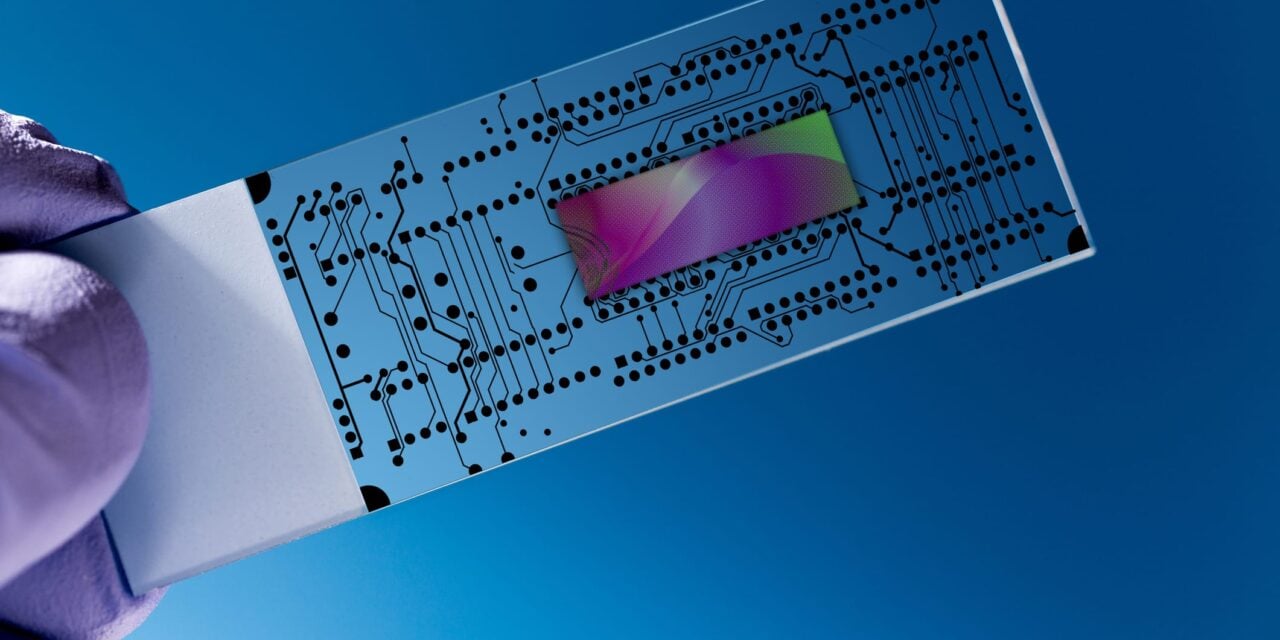

To move from observation to action, the clinical lab needs a technology that allows for spatial cell sorting—the ability to physically select and extract specific cells or regions of interest directly from a tissue slide for downstream analysis.

Currently, this is often attempted through crude methods like serial sectioning (slicing the next layer of tissue and hoping it matches the previous one) or laser capture microdissection, which can be labor-intensive and low-throughput. For spatial biology to become a routine clinical tool, we need “integratable technologies” that allow us to seamlessly transition from an image to a molecular sample.

Imagine a workflow where:

- Map: A high-content scanner creates a “spatial atlas” of the tissue.

- Identify: AI pathology algorithms scan the atlas and flag a specific region of interest —perhaps a cluster of immune cells that seem to be interacting with tumor cells in a novel way.

- Sort: Instead of scraping the whole slide, a targeted extraction tool allows the lab to physically isolate only that specific region of interest.

- Analyze: That precise packet of biological material is then fed into standard, gold-standard molecular workflows (like NGS or mass spectrometry).

This capability—to “sort” spatially—is what turns a pretty picture into a diagnostic result. It ensures that the molecular data we generate is pure and relevant, rather than diluted by the noise of the surrounding healthy tissue. It makes the “spatial atlas” actionable.

The Clinical Imperative: Closing the Prediction Gap

This integrated approach—map, identify, sort, analyze—is not merely academic; it addresses the most pressing failures in current diagnostics, particularly in oncology.

Consider the immunotherapy prediction gap. The current gold standard for many checkpoint inhibitor prescriptions is PD-L1 staining. Yet, we know that PD-L1 expression alone is an imperfect predictor. Many patients with high PD-L1 do not respond, while some with low expression do.

The failure often lies in the lack of mechanistic context. A “spatial sorting” approach would allow a lab to isolate the immune cells directly adjacent to the tumor and sequence them separately from those in the stroma. This precise interrogation could reveal whether the resistance mechanism is driven by the tumor (eg, lack of neoantigens) or the immune system (eg, exhaustion).

Current “whole slide” approaches average these signals together. By enabling the physical sorting of these distinct micro-neighborhoods, we can provide oncologists with a binary “go/no-go” based on the actual mechanism of the patient’s disease, rather than a probabilistic guess.

The Era of Integratable Technologies

We are standing at the threshold of a new era in diagnostics. The “map” era gave us the coordinates of biology. The “mechanism” era will give us the story.

But to read that story, we must integrate our technologies. We cannot have AI pathology living in one silo and molecular genetics in another. The future clinical lab will rely on platforms that bridge these worlds—tools that can take an AI-defined region on a screen and physically deliver the molecular truth of that region into a test tube.

By combining the high-resolution “where” of spatial atlasing with the “what” of deep molecular profiling—facilitated by precise spatial sorting—we can finally deliver on the promise of precision medicine. We will move beyond simply admiring the complexity of tissue to actively dissecting it, understanding it, and, ultimately, defeating the disease within it.

Author Bio: Amos Lee is the CEO of Meteor Biotech, a spatial biology company. With experience in biotechnology and business strategy, he focuses on the commercialization of next-generation genomic tools. He is dedicated to transitioning complex spatial technologies into scalable solutions that empower clinical labs and advance precision medicine.

ID 44548640 © Luchschen | Dreamstime.com