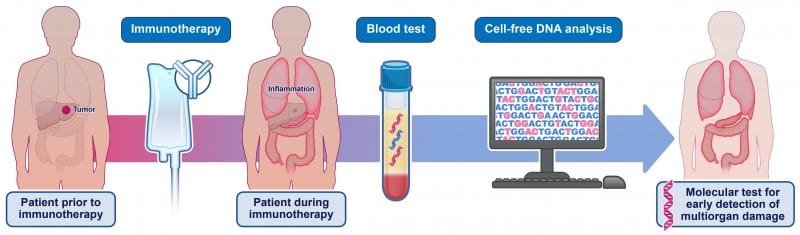

Johns Hopkins researchers found the blood test detected multiorgan tissue damage in patients experiencing immune-related adverse events from checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

A noninvasive blood test that measures cell-free DNA shed by tumors may help clinicians identify adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs before clinical symptoms appear, according to Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers.

In a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators described how they used cell-free DNA testing to identify tissue damage across nine organs in 14 patients with solid tumors receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The test showed that six patients who developed immune-related adverse events (irAEs) had evidence of multiorgan tissue damage at the time of, or before, their clinical diagnoses.

“To our surprise, our findings suggest the tissue damage was more systemic, and not restricted to single organs,” says Yuxuan Wang, MD, PhD, assistant professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and lead co-author of the study, in a release. “We saw evidence of multiorgan injury in all six patients with irAEs, along with roughly six times more tissue-specific cell-free DNA in their blood.”

The findings suggest that clinical syndromes diagnosed in patients may represent only a fraction of the underlying organ damage they experience, Wang says.

Detecting Damage Before Clinical Diagnosis

About half of patients receiving contemporary immunotherapies develop serious immune-related adverse events, which can be life-threatening if not identified early, according to Mark Yarchoan, MD, associate professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Unfortunately, we still lack reliable tools to identify which patients are developing these toxicities,” Yarchoan says in a release. “Our results suggest that cell-free DNA could offer a new way to detect these complications earlier.”

The study included six patients with irAEs and eight patients without adverse events. Researchers collected blood samples before treatment started and between weeks four and eight of therapy. The cell-free DNA test can detect damage to individual organs because each tissue has unique DNA methylation patterns.

In three of the six patients with irAEs, tissue damage preceded clinical diagnosis by four to 236 days. None of the eight patients without clinically documented irAEs showed evidence of multiorgan damage.

Need for Larger Validation Studies

Further validation in larger trials would be needed to determine how different causes of multiorgan damage affect cell-free DNA release and how the test could inform patient care, says Bert Vogelstein, MD, Clayton Professor of Oncology and co-director of the Ludwig Center at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

The test could potentially provide information about immune response to treatment and help identify patients at risk for irAEs who need additional treatment to prevent toxicities, Vogelstein says.

The letter’s co-authors include Howard L Li, Chetan Bettegowda, Kenneth W Kinzler and Nickolas Papadopoulos, all of Johns Hopkins.

Photo caption: A blood test may help clinicians identify adverse events related to immunotherapy drugs.

Photo credit: Elizabeth Cook