Summary: New evidence raises doubts about the effectiveness and ethical justification of the NHS trial for Galleri, a blood test claimed to detect over 50 types of cancer.

Takeaways:

- Trial Concerns: Leaked documents and expert opinions suggest the current NHS trial of the Galleri test is not suitable for justifying a national screening program, with serious ethical and scientific concerns raised about its implementation.

- Pending Results and Ethical Issues: Interim results of the trial were not compelling enough, delaying any rollout decision until 2026, while further scrutiny has been raised over the close ties between Grail and U.K. government officials.

- Public Risk and Private Profit: Grail faces a class action lawsuit in the U.S. for allegedly exaggerating Galleri’s effectiveness, highlighting broader issues of public risk for private profit, and calling for more rigorous and transparent review processes for medical technology in the UK.

New evidence published by The BMJ casts doubt on a much-hyped blood test for the NHS that promises to detect more than 50 types of cancer.

The test, called Galleri, has been hailed as a “ground-breaking and potentially life-saving advance” by its maker, the California biotech company Grail, and the NHS is currently running a £150m Grail-funded trial of the test involving more than 100,000 people in England, report Dr Margaret McCartney and investigative journalist Deborah Cohen.

What is the Galleri Test?

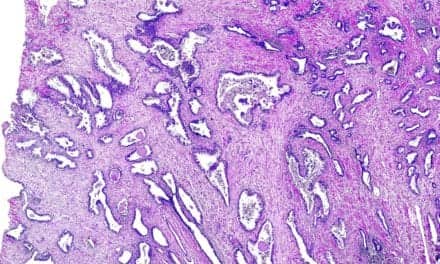

NHS England claims the test can identify many cancers that “are difficult to diagnose early,” such as head and neck, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers, and that if effective, could be used in a national screening programme.

Trial success would also hand Grail a lucrative deal with the NHS, which, if results are favourable, has agreed to buy millions of tests in exchange for a new state-of-the-art facility built by Grail in the U.K. Although contract details remain confidential, a single test in the U.S. currently retails for $950.

But documents leaked to The BMJ suggest that the trial is not suitable to justify a national screening test, while experts believe that Galleri has been over-hyped and that the current trial is unethical.

Even the chair of the UK National Screening Committee has privately voiced “serious concerns” to NHS England’s chief executive about the trial, according to emails seen by The BMJ.

Results of the Galleri Trial Are Still Pending

Interim results of the trial have not been published as expected this month. Instead, NHS England said the results were not “compelling enough” and a decision to roll out the test will wait until final trial results in 2026.

But as the trial continues, Freedom of Information requests by The BMJ raise further concerns over the close relationship between key government figures and Grail, including meetings with ex-prime minister Lord Cameron and Nadhim Zahawi, then minister in the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

An NHS England spokesperson said they believed that Grail was “now being subjected to one of the largest and most rigorous investigations done in any health-care system worldwide,” that no decision had been made and no further details were available.

By contrast, an NHS England source, speaking to The BMJ anonymously, said “The clinical or scientific data doesn’t stack up, but that should have come first. This is not the way to do a trial – it should be done transparently. It’s not been thought through at all.”

Grail Lawsuit

Added to these concerns, Grail is facing a class action lawsuit in the US. Embittered investors, faced with steep losses, claim the company exaggerated Galleri’s effectiveness in order to increase share price.

Richard Sullivan, director of the Institute of Cancer Policy, King’s College London, says that Grail is “a clear-cut case of public risk and private profit.”

Concerns surrounding the decision making process around Grail also serve as a timely reminder to the new Health Secretary, Wes Streeting, whose stated aim is to make the UK a “life sciences and medical technology powerhouse,” note McCartney and Cohen.

“The new government needs a more rigorous and transparent way of reviewing medtech clinical research, especially when it involves such widespread access to NHS resources,” adds Sullivan. “They also need to change their language. It’s all promissory science and hype. This serves no public good whatsoever.”