Laura Bechtel, PhD, DABCC; Jim Aguanno, PhD; Shalini Verma, MD FCAP

Summary:

Despite the availability of preventive measures and effective treatments, hepatitis B and C remain major global health threats due to persistent gaps in diagnosis, treatment access, and implementation of care, prompting updated international guidelines aimed at expanding screening, simplifying treatment, and accelerating elimination goals by 2030.

Takeaways:

- Diagnosis and treatment gaps persist: Only a small fraction of individuals with hepatitis B or C are diagnosed or receive antiviral therapy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, due to cost, complexity of care, and limited access to testing.

- Updated global guidelines aim for broader access: WHO, CDC, AASLD, and EASL now recommend universal screening and simplified treatment protocols, including expanded eligibility for antiviral therapy and streamlined testing strategies.

- Elimination by 2030 requires integrated, decentralized care: Achieving global elimination targets hinges on integrating hepatitis services with primary care, HIV, and harm reduction programs, especially for high-risk populations such as people who inject drugs and incarcerated individuals.

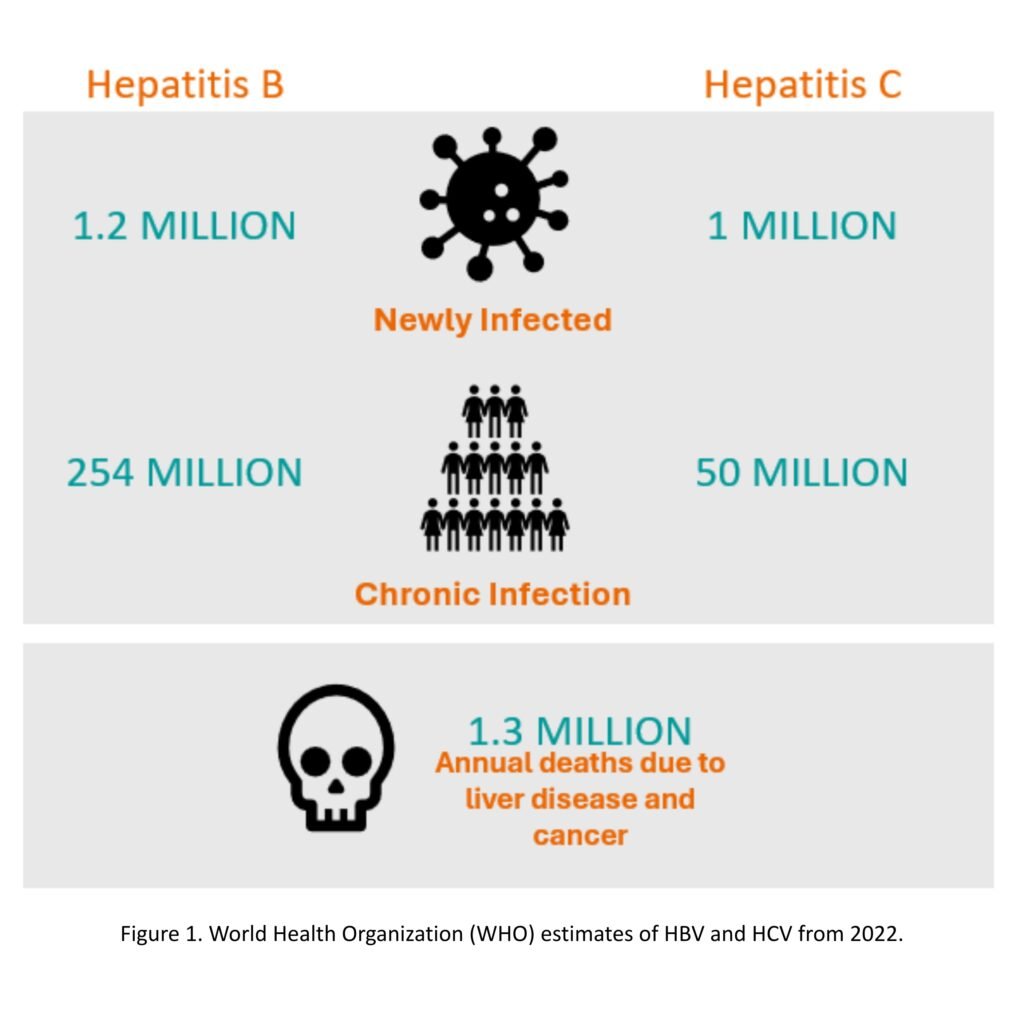

Hepatitis, an infection or inflammation of the liver most commonly caused by a viral infection, affects over 300 million people globally, with approximately 3,500 individuals dying each day from liver disease related to infection (Figure 1). There are six known hepatitis viruses: types A, B, C, D, E and G. Among these, hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) have been associated with an increased risk of cancer [1-8].

Hepatitis B & C Transmission Varies

HBV and HCV are transmitted from person to person through sexual contact or through the sharing of syringes or needles used for injecting drugs. They can also be spread during invasive medical, dental, or other procedures (e.g. tattoos or piercings) when contaminated equipment is used. Additionally, transmission can occur from an infected mother to her child during pregnancy or childbirth [1-8].

There is currently no vaccine available for HCV, and, although HBV vaccination programs have been implemented worldwide, both HBV and HCV remain significant causes of morbidity and mortality. This is largely because many individuals remain undiagnosed or do not receive the necessary treatment. [1-8]

Reports Point to Diagnosis and Treatment Gaps

Recent reports on global hepatitis incidence and prevalence have highlighted significant gaps and regional disparities in HBV diagnosis and treatment coverage, especially in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs). In 2022, only 13% of the 254 million people living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were diagnosed, and fewer than 3% received antiviral therapy. These low rates are partly due to the complexity and variability of clinical guidelines recommended by international liver societies, as well as the high cost of diagnostic tests, which are not routinely available in endemic regions and typically require out-of-pocket payment. At the same time, there is growing debate around expanding treatment criteria, particularly for individuals in the earlier stages of infection.[6]

Similarly, while effective treatments for hepatitis C exist, the ongoing rise in cases is primarily driven by the continued spread of the virus through intravenous drug use and related behaviors, coupled with other factors, including limited access to care and health disparities [1-8].

Given the consensus on the need for simplified and harmonized recommendations and supporting factors such as advanced diagnostic tests and emerging clinical data, the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated their HBV guidelines[6, 9-11]; in addition, WHO, AASLD, CDC Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) updated their HCV guidelines.[10, 12-15] These guidelines emphasize universal screening for HBV and HCV, in adults at least once in a lifetime and expanded testing strategies, marking a critical shift toward earlier detection, improved linkage to care, expanded treatment eligibility such as prophylaxis for pregnant women and reduction of HBV- and HCV-related morbidity and mortality.

Hepatitis Testing Overview

Hepatitis B

HBV consists of an outer lipid envelope and an icosahedral nucleocapsid core composed of core protein. The nucleocapsid encloses the viral DNA and a DNA polymerase that has reverse transcriptase activity. The outer envelope contains embedded proteins that are involved in viral binding of, and entry into, susceptible cells.

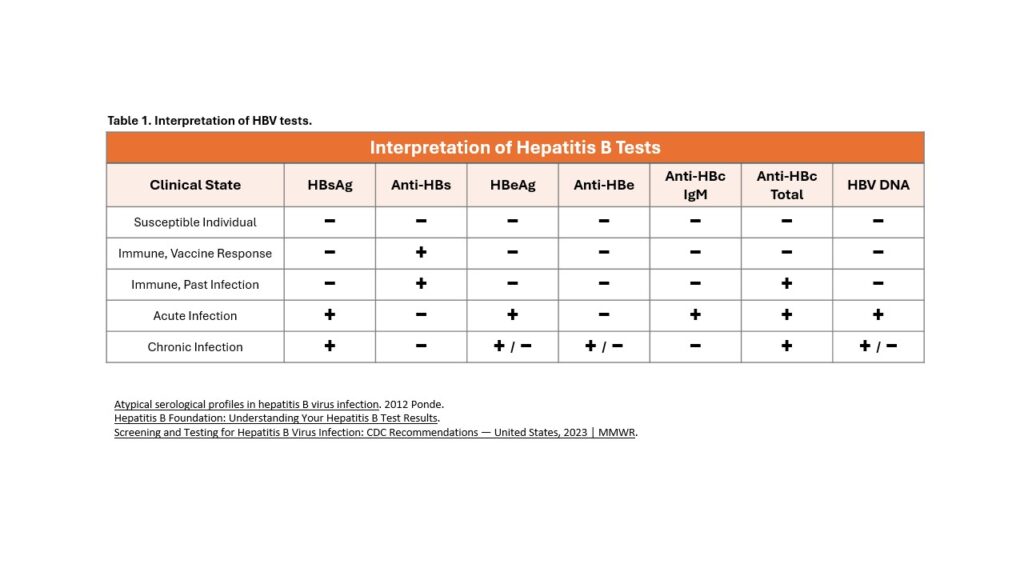

This structure gives rise to several serologic tests utilized to diagnose HBV infection and to determine whether a person lacks immunity to HBV (Table 1). In addition, there are multiple serologic and non-serologic tests used to risk-stratify and monitor patients with chronic HBV.[16-18]

- Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg): Structurally, HBsAg is the main outer surface protein of intact HBV. HBsAg is the first serologic marker to appear in a new acute infection, which can be detected as early as 1 week and as late as 9 weeks (range: 6-60 days), with an average of one month after exposure to HBV. The presence of HBsAg indicates active infection, except in the situation whereby HBsAg may be transiently present after receipt of a dose of hepatitis B vaccine.

- Hepatitis B Surface Antibody (anti-HBs): The appearance of anti-HBs follows declining HBsAg titers and indicates recovery from HBV infection. The presence of anti-HBs indicates either recovery from natural infection and immunity to HBV or a response to HBV vaccination with the development of immunity.

- Antibody to Hepatitis B Core Antigen Total (anti-HBc Total): The total anti-HBc includes IgM anti-HBc and IgG anti-HBc. The presence of anti-HBc indicates past or current infection with HBV regardless of whether the infection is acute, chronic, or resolved. Anti-HBc does not bind to intact virions since the core is surrounded by the viral envelope. Anti-HBc remains persistently detectable in most individuals following HBV infection, with the persistent anti-HBc predominantly consisting of anti-HBc IgG. The formation of anti-HBc is not seen following HBV immunization.

- Antibody to Hepatitis B Core Antigen IgM (anti-HBc IgM): Anti-HBc IgM is the first antibody to appear following acute HBV infection, and it typically becomes detectable within 6 to 8 weeks after infection and declines to sub-detectable levels within 6 to 9 months at which time most of the anti-HBc IgM is replaced by anti-HBc IgG. Anti-HBc IgM is the most reliable test for distinguishing acute from chronic HBV infection. An acute exacerbation (or liver flare) in a chronic HBV infection can also result in a positive anti-HBc IgM test result. The CDC recommends follow-up testing after 6 months in this case.

- Hepatitis B e Antigen (HBeAg): HBeAg is a protein secreted by the virus and is often detectable during the acute phase of infection or in individuals with CHB. The presence of HBeAg is typically associated with elevated HBV DNA levels and high infectivity, but it is variably present in persons with CHB infection. Its presence in the serum indicates the virus is actively reproducing and the individual is highly contagious.

- Antibody to Hepatitis B e Antigen (anti-HBe): The appearance of anti-HBe is generally associated with declining HBeAg titers and indicates a favorable immune response to HBV infection. The anti-HBe that appears following HBeAg clearance will generally persist, but unlike anti-HBs, it does not have a known role in controlling or neutralizing HBV infection, nor does it have any known role in preventing HBV infection.

- HBV DNA: The presence of HBV DNA indicates active infection (acute or chronic). Detection of HBV DNA is not typically used for diagnostic purposes, but it does play a major role in risk stratification and monitoring response to antiviral therapy.

Hepatitis C

There is no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C. Nearly 75-85% of people with hepatitis C are asymptomatic. Without testing, individuals are unaware they have disease and thus can unknowingly transmit HCV to others. Anti-HCV antibodies may not provide immunity against re-infection. Therefore, reinfection especially in high-risk groups is possible.

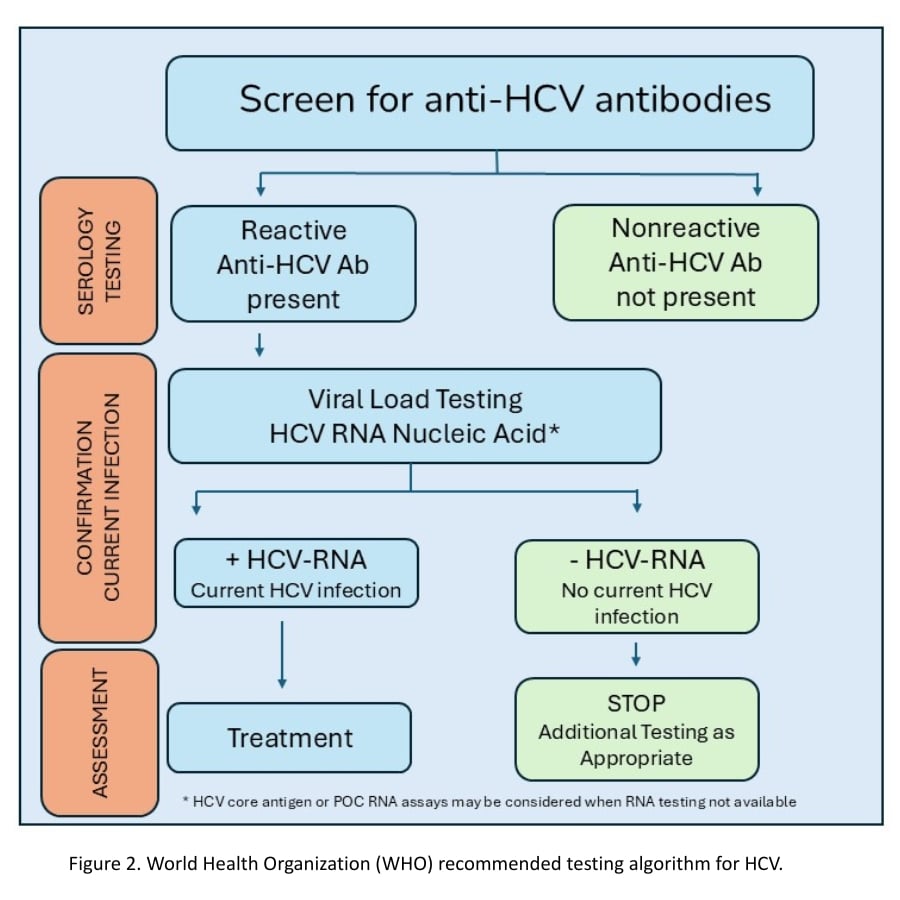

- HCV Antibody test: The presence of HCV IgG antibodies indicates active or previous infection (acute or chronic) with reflex to RNA if the antibody test is reactive.[19]

- HCV RNA test: the presence of HCV RNA is necessary to differentiate past from current infection. Repeat HCV RNA testing if the person tested is suspected of HCV exposure within the past 6 months or clinical evidence of disease. Immunosuppressed individuals with exposure risk and/or clinical suspicion may require HCV RNA testing even if HCV antibody test is negative.

Current Hepatitis Guidelines

The WHO set goals for elimination of viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. This includes 90% reduction in incidence and 65% reduction in mortality by 2030. Primary prevention, combining routine screening with treatment, reducing mother-to-child transmission, and addressing barriers faced by high-risk populations through equitable access to healthcare is a priority. Decentralizing viral hepatitis services to lower health facilities such as primary care, community- and health-facility-based services, integrating with other services such as harm reduction and HIV services to provide person-centered care and task-sharing for care and treatment delivery is key to reaching elimination of viral hepatitis.[20]

Screening. CDC and WHO guidelines for Hepatitis B and C have expanded to universal screening for all adults at least once in their lifetime, and all pregnant women during each pregnancy (preferably within the first trimester regardless of vaccination status or history of testing), and more frequent testing for susceptible populations, regardless of age with on-going risk of exposures.[10, 12]

HBV triple panel screen for adults, pregnant women, and periodic testing should include HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc total. Determination of the phase of HBV infection requires additional and potentially repeated tests including the measurement of HBV DNA viral load, hepatitis B e antigen and antibody, liver transaminases and fibrosis, to predict the risk of liver-related complications and provide appropriate monitoring and antiviral treatment indications.[6] Testing all infants born to HBsAg-positive people for HBsAg and antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) serology markers is also recommended.[21]

CDC and WHO guidelines recommend HCV serology with reflex to HCV viral load testing (Figure 2). HCV serology is anti-HCV antibody testing with reflex to qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA or HCV core antigen testing.

Treatment. Global strategies suggest treatment for HBV and HCV to all adults, adolescents and children who are eligible for treatment, especially those with more advanced disease, ensuring that the most effective treatment regimens are accessible and affordable to all populations. In the absence of effective treatment, an estimated 20-30% of people with chronic HBV or HCV infection will develop cirrhosis and are at risk of developing liver cancer. Recent WHO guidelines have updated prophylactic (for HBV) and treatment algorithms, monitoring for viral suppression for HBV and HCV.[20] Although complex in nature updated guidelines have attempted to simplify treatment regimens.

Antiviral therapy is intended to reduce virus particles to undetectable levels. This is linked to improvements in liver inflammation and fibrosis, the reversal of cirrhosis, a decreased risk of HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma), and lower liver-related mortality.

HBV Treatment

Antiviral treatment is typically unnecessary for uncomplicated symptomatic acute HBV, as about 95% of immunocompetent adults experience spontaneous recovery. Updates in AASLD and EASL recommend treating patients with cirrhosis if they have detectable viremia. Both WHO and AASLD guidelines recommend entecavir (for children ≥2 years) and tenofovir (for children ≥12 years) as first-line therapies for chronic hepatitis B with viremia. WHO guidelines expand treatment criteria among adults and adolescents over 12 years old, including pregnant women and girls living with chronic hepatitis B using tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) even when viral load or hepatitis B e antigen testing are not available. This is due to barriers limiting HBV DNA and hepatitis B e antigen testing contributing to poor clinical outcomes.[6] AASLD also includes tenofovir alafenamide, an orally available prodrug of tenofovir with similar antiviral efficacy but lower renal and bone toxicity

HCV Treatment

Simplified Treatment protocol for treatment-naive individuals include either 8 weeks of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) glecaprevir (300 mg)/pibrentasvir (120) mg for genotypes 1 through 6 or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir (400 mg)/velpatasvir (100 mg) for genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, or 6. HCV treatment can cure individuals and is identified by a sustained virologic response when HCV is no longer detectable in the blood 12 weeks or more after completing treatment. High rates for SVR are observed. Individuals with SVR will not transmit disease. Cases of re-infection can occur even for individuals with HCV IgG reactivity, likely due to a new infection of a new HCV genotype. Higher rates of reinfection are observed in high-risk individuals who inject drugs.

The Goal of HBV and HCV Elimination Continues

Viral hepatitis is a public health crisis in the United States and globally, resulting in morbidity and mortality, poor quality of life and high costs to health care systems. Achieving HBV and HCV elimination goals by 2030 require transformational plans through decentralization of care to lower-level facilities, integration with existing services such as primary care, harm reduction programs, prisons, and high-risk programs (HIV, people who inject drugs, substance use disorders) to ensure viral hepatitis surveillance, prevention, testing, and treatment services are widely available for all populations.

Featured Image: Jarun011 | Dreamstime.com

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Shalini Verma, MD, FCAP, is a diplomate of the American Board of Pathology with active board certifications in molecular genetics pathology, hematopathology and anatomic & clinical pathology. She completed her clinical fellowships and residency training at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, New York Presbyterian-Weill Cornell Medical Center, and the University of Southern California-Los Angeles General Medical Center. She also holds active medical licenses in California and Texas. Shalini has over 15 years of experience in various aspects of clinical laboratory medicine through her roles as clinical laboratory medical director and global medical affairs executive for organizations like Roche Molecular Systems, Siemens Healthineers, and GE Healthcare. She currently serves as a medical officer with Siemens Healthineers.

Jim Aguanno, PhD, has over 40 years of experience in laboratory medicine. He received a BS in Chemistry and a PhD in biochemistry from Memphis State University. Following his PhD, he did two post-doctoral fellowships: one at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in biochemistry and a second fellowship in laboratory medicine at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. Aguanno is currently senior clinical consultant in Medical Affairs at Siemens Healthineers.

Laura Bechtel, PhD, DABCC, completed her post-doc and Clinical Chemistry fellowship at the University of Virginia. Her PhD is in pharmacology and toxicology and she has an M.S./B.S. in microbiology. She has 15 years experience as a clinical director at reference laboratories and healthcare systems and 15 years research experience. Laura is now at Siemens-Healthineers as a medical sciences partner in Medical Affairs to support laboratorians and providers with utilization of test methodologies focused on improving patient care.

References

- JE, M., Hepatitis B: global importance and need for control. Vaccine 1990; 8 Suppl:S18. . Vaccine, 1990. 8.

- Ott, J., et al., Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine, 2012. 30: p. 2212-2219.

- Global hepatitis report 2017. 2017, World Health Organization.

- Hepatitis B. 4/9/2024 4/24/2025]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

- Hepatitis B. Fact sheets 2024 4/28/2025]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

- Wong, G. and M. Lemoine, The 2024 updated WHO guidelines for the prevention and management of chronic hepatitis B: Main changes and potential implications for the next major liver society clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Hepatology, 2025. 82: p. 918-925.

- Global Viral Hepatitis. 6/6/2024 4/24/2025]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/global/index.html.

- Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2024: World Health Organization.

- Lampertico, P., EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology, 2017. 67: p. 370-398.

- Moorman, A., et al., Testing and Clinical Management of Health Care Personnel Potentially Exposed to Hepatitis C Virus — CDC Guidance, United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2020. 69(6).

- Terrault, N., et al., Update on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 Hepatitis B Guidance. Hepatology, 2018. 67(4).

- Bhattacharya, D., et al., Hepatitis C Guidance 2023 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases– Infectious Diseases Society of America Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2023.

- EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series. Journal of Hepatology, 2020. 73.

- Chou, R., A. Avihingasanon, and S. Hamid, Updated recommendations on treatment of adolescents and children with chronic HCV infection, and HCV simplified service delivery and diagnostics. World Health Organization, 2022.

- Updated recommendations on HCV simplified service delivery and HCV diagnostics: policy brief. Geneva: World Health Organization;, 2022.

- Hepatitis B Surveillance Guidance. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance – United States 3/14/2024 4/24/2025]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/surveillanceguidance/HepatitisB.htm#section3.6.

- Understanding Your Test Results. Blood Tests for Diagnosis of Hepatitis B 4/24/2025]; Available from: https://www.hepb.org/prevention-and-diagnosis/diagnosis/understanding-your-test-results/.

- Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2024 March 2024; Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090903.

- Testing for HCV infection: An update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. . 2013, CDC: MMWR.

- Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the perios 2022-2030. 2022, World Health Organization.

- Corcorran, M. and D. Spach. HBV Screening Recommendations. HBV Screening, Testing, and Diagnosis 2023 3/13/2023 4/24/2025]; Available from: https://www.hepatitisb.uw.edu/go/screening-diagnosis/diagnosis-hbv/core-concept/all.