The following is a companion article to the CLP feature, “Women and Cancer.”

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) encompass a wide range of commonly recognized infections, including chlamydia, bacterial vaginosis, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus (HSV 1 and 2), human papillomavirus (HPV), and Trichomonas vaginalis. Signs and symptoms of such infections differ, and can sometimes disappear or be altogether absent, leading to a failure to treat the conditions.

Most STDs will resolve if treated, and they are not generally believed to be a factor in the development of cancers affecting women. But in a few cases—especially if permitted to linger untreated—STDs are thought to interact with other pathogens in ways that favor the growth of various types of cancer. (Table 1)

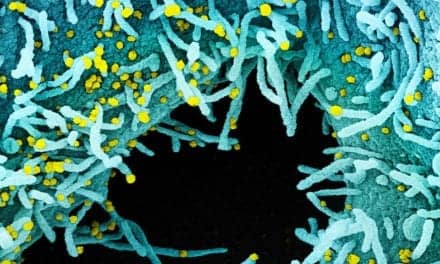

Human papilloma viruses (HPVs) offer an example of the oncogenic potential of STDs that researchers are still working to discover and understand. HPVs encompass a group of more than 100 related but genetically distinct viruses that can produce warts in a variety of areas of the body. There is no known treatment for the virus except removal of the cells and tissues found to be infected.

At least a dozen types of HPV are considered high-risk infections, as they have been shown to be the main causes of cervical cancer. Although a low percentage of women infected with HPV develop cervical cancer, nearly all women who develop cervical cancer show signs of infection with the virus.

Last April, FDA approved an expanded indication for use of the Cobas HPV test by Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, making it the first test approved as a first-line primary screening test—instead of Pap testing—for women aged 25 and older. A molecular diagnostic, the Roche test is performed on the company’s Cobas 4800 analyzer, which automates PCR amplification and detection to reduce operator requirements. The system requires approximately 30 minutes of operator hands-on time to initiate a run of 24 or 96 samples.

The Cobas HPV test simultaneously provides a pooled result for 12 high-risk HPV genotypes, and individual detection results for the highest-risk genotypes—HPV 16 and HPV 18—which together account for about 70% of all cervical cancer cases.

The same molecular diagnostics platform also runs Roche’s tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea, and tests for BRAF and EGFR gene mutations.

Chlamydia is a common and treatable STD. Women are infected with chlamydia at a rate of 2.5 times the reported rate of infection in men. Some research has suggested that persistent chlamydia infection may prevent the body’s DNA damage response from operating correctly, leading to the proliferation of wounded cells that may later be infected by oncogenic agents. In this way, at the cellular level, chlamydia may contribute to the development of some forms of cancer.1

To prevent such cellular damage from occurring, early detection and treatment are important. Cepheid, Sunnyvale, Calif, has developed the Xpert CT/NG test for the detection and differentiation of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG). The cartridge-based, qualitative, real-time PCR test uses urine or female swab samples, and runs on Cepheid’s GeneXpert family of analyzers. Hands-on time is less than a minute, with results delivered in 90 minutes.

Not all such tests make use of molecular technologies. Quidel Corp, San Diego, has developed the QuickVue chlamydia test, an immunoassay system that uses endocervical swab and cytology brush samples, and is performed in a self-contained cassette. The test delivers results in 12 minutes or less, and has overall sensitivity of 92% and overall specificity of 99%.

Trichomonas vaginalis is more common than chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, and HPV infections. It has been thought that Trichomonas infection may increase the risk of developing certain cancers. In an 11-year prospective study conducted among Chinese women in a cervical screening program, however, the postulated association between Trichomonas and cervical cancer was found to be relatively weak. The study results suggested that, “there might be an association between T. vaginalis infection and the risk of cervical cancer,” wrote the authors, “but only 4% to 5% of cervical cancer in Chinese women may be attributable to T. vaginalis infection.”2

Sekisui Diagnostics LLC, Lexington, Mass, offers the OSOM Trichomonas rapid test for the qualitative detection of Trichomonas vaginalis. The CLIA-waived immunochromatographic assay uses a vaginal swab sample, and is performed with disposable swabs, tubes, and reagents provided in the test kit. Sekisui claims that the test offers sensitivity of 83% versus culture, and 95% agreement with culture and wet mount combined.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is among the most commonly reported STDs, and has also been considered a potential cofactor in the development of cervical cancer. It is thought that BV may in some way interact with HPV infection to trigger neoplastic alterations leading to cervical cancer—explaining why relatively few women infected with HPV alone develop cervical cancer—but clear evidence of such a mechanism has not been found. Nevertheless, a systematic review of previous research into the associations between BV and the precursors of cervical cancer found a positive association to the development of precancerous lesions, and recommended further study to determine whether BV plays a role in promoting the development of cervical cancer.3

Fortunately, once diagnosed, BV is generally treatable with oral or vaginal antibiotics. Sekisui Diagnostics has developed the OSOM BVBlue test for detecting elevated vaginal fluid levels of sialidase, an enzyme produced by bacterial pathogens associated with BV, including Bacteroides, Gardnerella, Mobiluncus, and Prevotella. The CLIA-waived immunoassay requires 1 minute of hands-on time, and provides results in 10 minutes. Sekisui claims that the test is 92.8% sensitive and 98% specific versus the standard test based on Gram stain.

References

1. Chumduri C, Gurumurthy RK, Zadora PK, Mi Y, Meyer TF. Chlamydia infection promotes host DNA damage and proliferation but impairs the DNA damage response. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;13(6):746–758; doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.010.

2. Zhang ZF, Graham S, Yu SZ, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis and cervical cancer: a prospective study in China. Ann Epidemiol. 195;5(4):325–332.

3. Gillet E, Meys JFA, Verstraelen H, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45201; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045201.