An international research consortium led by Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) has tested a rapid new analytical tool that needs just a blood sample from the fingertip.

Around 240,000 children worldwide die of tuberculosis every year. The disease is among the top ten causes of death in children under the age of five. One of the main reasons for this mortality is that tuberculosis is often misdiagnosed or not diagnosed in time, particularly in regions with limited resources.

A new diagnostic tool, which an international research consortium led by LMU medical scientists Laura Olbrich and Norbert Heinrich from the Division of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine at LMU University Hospital Munich has tested as part of a large-scale study in five countries, offers significant progress in this area. The authors report on their findings in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

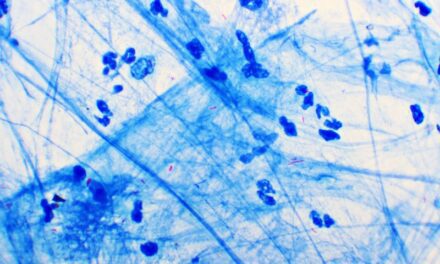

Before now, the most commonly used tuberculosis tests have been based on microbiological analysis of sputum—that is, mucus taken from the lower airways. These samples are difficult to obtain in children. Moreover, child tuberculosis is often characterized by a low bacterial load and unspecific symptoms. “Therefore, new tests are urgently needed,” says Olbrich.

Rapid Blood Test

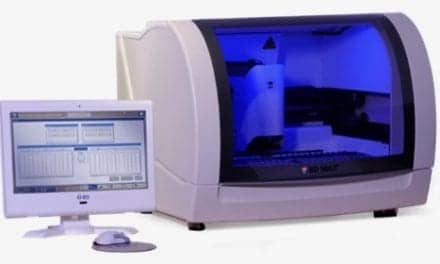

The new tool, which the researchers have now tested, is based on the activity of three specific genes, which can be measured in capillary blood. An innovative, semi-automatic system allows health care workers to identify a so-called transcriptomic signature for these genes. This transcriptomic signature can help to diagnose tuberculosis. The test has the advantage that the blood sample can be conveniently taken from the fingertip and the results are available very quickly: “We have the results in just over an hour. For most other tests, the samples have to be sent to other laboratories for analysis,” says Olbrich.

Further reading: Device Using Dielectrophoresis Could Improve Tuberculosis Detection

The researchers have tested the new tool as part of the comprehensive RaPaed-TB tuberculosis study, which is led by Heinrich and carried out in collaboration with partners in South Africa, Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, and India. In total, the study included 975 children younger than 15 years suspected of having tuberculosis. To determine the accuracy of the test, the researchers additionally investigated the tuberculosis status of the children using a standardized reference test, which is based on the analysis of sputum and bacterial cultures.

“The results were encouraging,” says Olbrich. “Compared to detection in culture, the test identified almost 60 percent of children with tuberculosis, with 90-percent specificity. This makes the test comparable with or better than all other tests that work with biomarkers. The bacterial culture is always the reference because it yields the most stable results. But it takes up to eight weeks and is often not available where children with tuberculosis present.”

As the reference signature of the new tool was largely identified from adult samples, the researchers expect that the test accuracy can be further improved after adjusting the calculation of the signature for children.