In clinical labs, application of informatics systems covers a growing range of uses

By Gary Tufel

Like the variety of clinical labs in the marketplace, modern lab informatics systems encompass a wide variety of functions. Use of such systems means something different to every lab that applies them to their unique environment and requirements.

“Clinical labs use informatics for a wide variety of things, including billing, staffing, equipment downtime, specimen and results management, test reporting, document control, quality assurance, and quality control,” says Lonnie D. Stallcup, BS, MT, continuous process improvement manager at the Laboratory Alliance of Central New York LLC (Lab Alliance), Syracuse, NY.

Laboratory management and executive staff use informatics to fulfill a variety of needs, adds George Popp, vice president of information systems at Lab Alliance. These include monitoring turnaround times for lab test reporting, recording the quality of specimens received, ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements, and more. “The use of internal and external data to drive the changes necessary for success is critical to lab operations,” he notes.

Laboratories make especially good use of informatics systems along the main path of functions that enable them to produce test results—the core functions of their laboratory information system (LIS)—but they sometimes don’t pay enough attention to functions incorporated in their LIS that could further streamline work, improve financial returns, or inform them of important information.

“When an LIS is purchased, lab owners are focused on getting their personnel trained and their lab up and running,” says Janet Chennault, MT(ASCP), vice president and cofounder of Schuyler House, Valencia, Calif. “But the impetus for fine-tuning a system utilizing existing utilities, or adding modules that will give the lab advantages, would come from management personnel, who typically excuse themselves from training,” Chennault says. “As a result, labs tend to use their LIS heavily for testing operations, but only occasionally for management purposes.”

Figure 1. Combining and collectively analyzing data from external systems to find ways that further impact healthcare outcomes and costs will become essential in a value-based healthcare environment. Diagram courtesy Orchard Software.

Each department on the healthcare team may have its own information system—billing systems, electronic medical records (EMRs), hospital information system, pharmacy information system, radiology information system, and so on—each designed to manage the workflow of their specific department (see Figure 1). Each system has some reporting, query, or alert capabilities relevant to the specific needs of the department that may be referred to as informatics, say Curt Johnson, COO, and Matt Modleski, vice president of business development at Orchard Software, Carmel, Ind.

Whether a lab refers to such operations under the rubric of “informatics” or “information technologies” (IT) may depend on the number of IT staff who are under the direct control of the labs, says Brian R. Jackson, MD, vice president and chief medical informatics officer at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, and associate professor of clinical pathology at the University of Utah. “In many cases the IT staff may be very small, and its functions may be limited to those directly available through the LIS,” he says. “A larger IT staff may permit a larger degree of automation and use of middleware. An even larger IT staff—such as those at the University of Michigan Health System, or a lab such as ARUP that operates a national or regional reference lab—can open up far more opportunities for in-house development of informatics applications,” Jackson says.

Whatever the role of lab informatics was in the past, it has certainly increased with the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. “Healthcare reform goals are to improve individual patient care, and overall population health, while decreasing costs,” says Sandra Laughlin, Labdaq product manager for CompuGroup Medical US, Owings Mills, Md. “Laboratory integration and business analytics are critical as we move from a fee-for-service model to a patient outcome payment model. It’s important that discrete data be captured, analyzed, and shared. With decreasing reimbursements, labs are also using informatics tools to monitor and improve efficiencies,” she says.

“Reform efforts are pushing toward value-based medicine, with reimbursements becoming more capitated,” agree Orchard’s Johnson and Modleski. “This attention directed at reducing costs and simultaneously improving the health of the population has spurred a renewed look at how we can more effectively use the enormous quantity of healthcare data that is collected—and lab data is a large portion of the clinical data involved.

“In order to achieve healthcare reform goals, organizations have to be able to intelligently use the healthcare data that is collected,” they add. “So health informatics becomes essential in the move toward improving patient outcomes and being more resourceful with healthcare dollars.”

LABS’ MOST-USED INFORMATICS FUNCTIONS

In clinical laboratories, informatics functions are often used to address business and management issues that include billing, staffing, and facilities management. Very frequently, a lab’s informatics functions also encompass testing operations, including equipment status and throughput, specimen and results management, and test reporting. The list doesn’t stop there, and labs may pick and choose to emphasize and elaborate on certain functions to fit their particular needs.

At Lab Alliance, says Popp, informatics is also used by the marketing and sales staff, who monitor client utilization of individual tests in order to determine whether to bring the test in-house; and by compliance staff, who ensure that regulatory mandates are met. Informatics systems are also used to monitor and resolve potential security risks to computer systems and networks.

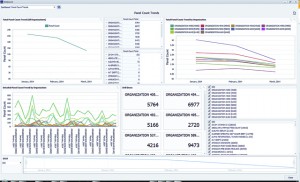

Figure 2. Dashboard products are often used to provide quick visibility for such business and management issues as turnaround times, testing volumes, costs, user productivity, ordering patterns, and quality improvement processes. Image courtesy CompuGroup Medical.

Laughlin notes that informatics systems are often used to address business and management issues. Many dashboard products are available that provide quick visibility to turnaround times, testing volumes, costs, user productivity, ordering patterns, and quality improvement processes (see Figure 2).

Laboratory results are also a large part of a patient’s overall EMR. Such lab data are typically deidentified and exported to a third-party system to enable medical facilities to develop performance metrics and measure clinical outcomes

At ARUP, according to Jackson, billing and management issues are less a matter of informatics systems than of the lab’s basic infrastructure of operational information technologies. “In theory, testing operations are all covered under routine LIS functions,” he says. “But in practice, most more-sophisticated labs end up needing third-party middleware or some in-house customization.”

Beyond that, some academic labs are heavily involved in research informatics—Jackson cites the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center as a good example—and some of those also expand their use of informatics into clinical applications. “At ARUP, it’s all of the above,” Jackson says. “I would classify lab operations as IT rather than informatics, but recognize that it’s very important. ARUP’s nonoperations informatics applications include test utilization analytics and online decision support.”

WHERE INFORMATICS SYSTEMS RESIDE

The evolution of informatics has resulted in a variety of systems with varied capabilities—some more sophisticated than others. Older and smaller LISs are sometimes supplemented using middleware and stand-alone programs that perform discrete functions not included in the original system.

“We often notice that our system’s ‘features’ are the sole products of separate companies that specialize in programs for barcode generation, automatic faxing, billing, Internet orders and results delivery, system interfaces, and so on,” says Chennault. “So you could add on systems that would do other jobs (though there may be problems with integration, of course).

“But in such a situation, many of the informatics functions would not be part of the LIS,” she adds. “Most modern LISs incorporate most or all of these capabilities. In that case, the informatics are located within the LIS.”

Stallcup’s laboratory draws information from several different systems. “Although we pull information from our LIS to aid in making decisions, we use a separate system to document quality assurance issues. We also have a dedicated system for document control, and two in-house-developed SEQUEL databases that track, maintain, and generate reports on all company sales activity and client satisfaction,” he says. “We are fortunate to have a dedicated information systems department to set up and maintain our various informatics needs.”

ARUP uses a Cerner Millennium LIS that covers most operational and many financial functions. But the lab supplements this system with a lot of third-party and in-house-developed software, says Jackson, and it manages most lab operations and billing functions under its IT department. “ARUP has a separate department for operational bioinformatics (mostly for genetics and molecular oncology) that does its own software development,” he says. “We also have a clinical informatics group that handles product management for all client-facing web applications, such as order entry, result retrieval, document-based charts, and online lab test selection and interpretive guidance.”

USING INFORMATICS CAPABILITIES

Laughlin says that many labs are not using informatics systems to their full potential. Although labs might be gathering deidentified patient data for trending and to assist with predictive analytics, the majority of lab facilities stop far short of such sophisticated applications, using their systems mostly to capture data in order to monitor operational efficiencies.

Clinical labs are using informatics to help them operate more efficiently. Laboratories have come to realize that informatics can play an important role in helping them justify their requests for resources, whether those involve staffing or instrumentation, says Stallcup. “Lately, we have been using informatics to understand our workload, and to ensure that we are staffing to the demand of that workload,” he says.

Nevertheless, says Stallcup, some labs still need to be convinced to leave behind the use of manual methods for collecting and reporting data. “Our labs previously documented the specimens received in the laboratory on the patient’s requisition, making the process for referring back to that information quite tedious and time-consuming,” he says. “But as we introduced Lean into our culture, we developed a method to record specimen information in our LIS as tests are being ordered. Now, anyone with access to our LIS can retrieve specimen information easily and quickly.”

And even where labs are already using electronic methods—such as for tracking quality control activities—some continue to generate paperwork to document issues for surveyor review. “Perhaps some labs have not adopted such means because of the costs of software, which would allow them to document electronically,” says Stallcup. “In a time when reimbursements are diminishing, some new technologies may be given low priority.”

To take full advantage of informatics systems, says Jackson, the key issue is the extent to which labs engage in upstream (test selection and ordering) and downstream (result review, interpretation, and cognitive integration) processes. “These functions require getting outside the LIS and into the clinician’s world, where EMRs play a big role,” he says. “Labs should insist on having control or management of EMR test menus, both for computerized physician order entry and for the organization of the results display. But labs need to recognize the severe usability limitations of currently available EMRs and look for opportunities to supplement those functions.”

Improving a lab’s use of the informatics capabilities at its disposal is sometimes just a matter of asking, says Chennault. When installing a new LIS, a lab’s attention is naturally focused on getting the facility up and running. But once the lab is in steady production, someone should still be looking at how its systems’ capabilities can be optimized. “Often, the information needed to do this is in the manual, or only takes a call to support to discover.”

As an example, Chennault cites the integrated billing system in her company’s SchuyLab LIS. In addition to sending claims to a patient’s primary insurance carrier, the system can also be used to record the payments received and automatically generate billing of the remainder to a secondary insurance carrier or the patient. “Many labs just write this off (which is customary, but not legal in many cases),” says Chennault. “But this can make a difference in millions of dollars in revenue for a moderately sized reference lab.”

“It takes someone with a broad view to notice that money is being lost, and to research what to do about it,” she adds.

INFORMATICS AND RESEARCH

Although informatics systems offer the capabilities necessary for clinical labs to participate in research activities—such as those related to the development of new clinical tests, or for drug discovery—sources agree that most labs are not making use of such capabilities.

“Most of the time, a regular lab does not perform clinical studies. Rather, it is a case of specialized research labs realizing that informatics systems can make their lives easier,” says Chennault. “Research and veterinary labs are accustomed to being the ‘red-headed stepchild’ of the laboratory industry. They may not know that an LIS system can improve their workflow.”

Further upstream from drug and diagnostics discovery, says Jackson, academic labs are even more likely to use IT resources to support grant-funded research. “Development of new tests in a clinical lab setting is usually more about validation and side-by-side comparisons, as opposed to discovery per se,” he says. “Most of the discovery historically comes from basic research labs as opposed to clinical labs.”

But future activities in drug discovery and molecular diagnostics development will definitely require the use of informatics systems to manage the large amounts of data generated, says Laughlin. And as these markets grow, she adds, the use of informatics systems will continue to expand. (For more information, see the companion article, “Informatics in the Clinical Lab.“)

PREVENTING SECURITY BREACHES AND PROTECTING PERSONAL DATA

Security breaches involving the release of client data have occurred across a wide range of organizations and entities, with the top targets including financial and retail establishments. But recent large breaches involving regional affiliates of Blue Cross Blue Shield have pointed out that all healthcare organizations are more than merely potentially vulnerable—they could, in fact, become targets of choice. Are current practices in lab informatics up to the challenge of preventing such breaches and protecting personal health information in clinical labs? What more do labs need from informatics technologies?

For good reasons, clinical laboratories have traditionally been located in remote environments, secure from potential damage to expensive and complex analyzers, or from the potential of transmitting infectious diseases. But now, that tradition of isolation is being challenged by the need to send and receive information electronically. “Nothing is going to make a lab safe from the highest levels of cyber assault, but very reasonable actions—a good modem password, firewall, and restricted personal use—can keep a lab’s data safe from casual attack,” says Chennault. “What laboratories are asking for now is not better cyber security, but better tracking of the actions of personnel who have legitimate sign-ons for the LIS.”

In Popp’s lab, the LIS is kept as isolated as possible from other systems. Only lab staff and vendor support staff are allowed access. The main security threats come from network breaches or breaches of other systems and devices. “We employ several layers of security to protect communication containing electronic personal health information (PHI). E-mail containing PHI is automatically encrypted by software looking for ‘key’ words or phrases. Complex passwords are used throughout the company, and security audits for all aspects of security are performed periodically by outside vendors. Staff are educated and re-educated on the importance of following security policies. The information gathered by various software products is used to determine if the security measures are performing as expected,” Popp says.

“We are constantly working to protect both our patient and business information from security breaches,” says Stallcup. “Fortunately, we have a dedicated information systems department that has not only implemented software to guard us from these attacks, but is also constantly educating staff about electronic threats and social engineering.”

Chennault observes that all of the labs belonging to her company’s more than 900 customers are careful with respect to security concerns, but they are not staffed by security professionals. Nevertheless, she says, “we have never had a report of one of them being hacked.”

According to Jackson, the HITECH Act has been effective in stimulating clinical organizations—including labs—to beef up their IT and compliance capabilities and processes.1 But the real reason labs haven’t suffered from more security breaches, he says, is that hackers appear to have determined that big health insurers are a better source for stealing social security numbers and other private data. “But that could always change,” he says.

RECENT TRENDS IN CLINICAL LAB INFORMATICS

The 2014 change in US Department of Health and Human Services policy that now permits patients to receive their test results directly from laboratories is having important consequences for laboratory informatics.2 “It has reinforced the concept that patients have an inherent right to their own bodies—and to information derived from their own persons,” says Chennault. “And this has galvanized the industry to step down the path to consumer results and direct-to-consumer testing.”

Meanwhile, labs must still contend with the realities of the current environment—including an ongoing shortage of technologists and technicians, and diminishing reimbursement for healthcare costs. “We have to use informatics to help us work smarter and not harder,” says Stallcup. “One important development in the lab has been the process of result autoverification. By establishing a system that allows ‘normal’ results to be automatically and electronically filed, we are able to free up tech time that can be spent in a more demanding task.”

But continuing changes in the ways that healthcare providers are structured and paid suggest that even greater advances lie ahead for the realm of laboratory informatics. “As health systems shift toward capitated contracts, we’ll hit a tipping point where suddenly everyone will realize that collectively, we need to actively manage the effective and efficient use of laboratory tests,” says Jackson. “This will require a huge new set of informatics capabilities to support clinicians—capabilities that do not currently exist in LISs or EMRs. And this will drive some very interesting technologic change.”

Gary Tufel is a contributing writer for CLP. For further information, contact CLP chief editor Steve Halasey via [email protected].

REFERENCES

- “Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act [HITECH Act],” American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Div. A, Title XIII; and Div. B, Title IV. PL 111-5. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr1enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr1enr.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2015.

- “CLIA Program and HIPAA Privacy Rule; Patients’ Access to Test Reports.” 79 Federal Register 7289–7316 (February 6, 2014); available at: https://federalregister.gov/a/2014-02280. Accessed March 25, 2015.