The needs of clinical labs have not changed much over the years, but the tools they use have. The LIS, a tool itself, must interface with them all while meeting higher expectations for its own performance.

|

The needs of the laboratory really haven’t changed. [Labs] still need to deliver patient results to providers in the most efficient and cost-effective manner they can. They still need to comply with all the regulatory requirements. And in these economic times, they still need to do more with less,” says Neal Flora, CEO of Fletcher-Flora Health Care Systems Inc in Anaheim, Calif. What has changed, according to Flora, is their sophistication in terms of technology. “They now have a much better grasp of what technology is available to help achieve those goals,” Flora says.

Subsequently, laboratories are asking more from the LIS. They want greater connectivity to other systems, such as EMRs, practice-management systems, and patient portals; more built-in safety checks; expanded capabilities to match growing areas, such as molecular testing and anatomic pathology; and increased efficiencies, in terms of productivity, billing, and outreach.

|

| Orchard Gastric Report |

These demands drive LIS functionality along with the available technology and prevailing environment. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) has provided the medical industry additional incentive (ie, money) to upgrade its information technology. Although this is primarily in the form of EMRs, the push has had an indirect impact on the LIS industry.

The incentives are tied to “meaningful use” of an EMR, meaning it is not enough to simply have an electronic health record system. Clinical data must be delivered to the relevant health care providers when and where they need it to make appropriate clinical decisions. “There are 29 measures associated with the incentive program of ARRA for 2011, 2013, and 2015, and 11 of them, or 33 percent, specifically talk about how lab testing and lab results are handled,” says Kelly Feist, vice president of marketing for Sunquest Information Systems in Tucson, Ariz.

Interface-to-Interface

|

Although facilities don’t receive federal funds for the implementation or upgrade of an LIS, the LIS is increasingly expected to interface with all types of systems.

“We’ve also seen an increased interest in developing interfaces to reference labs as well as reference labs exporting results from the LIS into the hospital EMR,” says Sandy Laughlin, LabDAQ product manager for Antek Healthware LLC in Reisterstown, Md. She cites increased competitiveness as a driver for both agents.

The most common interface, however, is the EMR, which cannot maximize its value without laboratory data. “Sixty percent of a patient’s electronic health record is lab results,” Flora says.

The difficulty with integration is the large number of EMRs with which an LIS must interface. “There are many different small vendors, as well as different versions of their software, which may not be capable of receiving results. So it’s a challenge in terms of the diversity of connections that are required for a laboratory—commercial or hospital—to really connect to these EMRs,” says Gilbert Hakim, CEO of SCC Soft Computer in Clearwater, Fla.

It is therefore possible that even with a long list of successful previous integrations, there can be new systems with which an LIS must connect. In the past, implementation of a new IT solution could take several weeks, but LIS vendors have pushed to shorten that time frame. “We’ve added a host interface scripting engine to implement a complete system, including interfaces to non-lab software, in a very short time frame,” Flora says.

Interface-to-Physician

|

Another challenge is the number of connections that must be made without an EMR. “Some facilities have made EMRs a priority, while others won’t implement until they are forced to do so,” Laughlin says.

Generally, EMR adoption has progressed in hospital settings, but physician practices have been slow to move. “I think it’s safe to say that the adoption rate [for ambulatory practices] is currently somewhere between 20 and 30 percent,” says Laughlin, citing studies by Healthcare IT News and the New England Journal of Medicine as resources.

The ARRA incentives are designed to encourage these providers to adopt EMRs, but confusion about meaningful use and eligible systems has contributed to continued slow acceptance. “Meaningful use doesn’t necessarily mean you are mandated to have an electronic medical record,” Feist says.

Labs must therefore find ways to connect with physicians who do not yet have an EMR or a practice-management system. “This is where hospitals can extend a different solution—a Web- or browser-based solution—to physicians in the community to allow them to perform electronic ordering of lab and radiology tests, see results electronically, and even provide them with a way to do e-prescribing,” Feist says.

Facilities that can manage this will increase their competitiveness, and the LIS can assist with this objective. LIS vendors have sought to fill this hole with cloud computing (Internet-based) technologies. With these systems, physicians can interface digitally—and meaningfully—with the laboratory through the Web, without needing specialized software.

“The LIS can help [hospitals] extend or strengthen their relationships with their community-based physicians to ensure their standing in the community. They can help grow revenue via laboratory outreach programs. And they can support other outpatient services like outpatient surgery,” Feist says. Many LIS vendors have added Web-based capabilities to their software, some even before the ARRA was passed.

Interface-to-Face

Similarly, some LIS vendors are looking ahead to the future, when patients will want direct access to their health information to store in their own files, referred to as personal health records, or PHRs. These are not commonplace yet, but with companies such as Microsoft Corp and Google developing PHR services (Microsoft HealthVault and Google Health, respectively), many predict their ubiquity in the future.

Exactly how the architecture will look is still in development, but it’s reasonable to expect the EMR to handle the bulk of this activity, in part because the PHR will include all health information, not just laboratory results. However, because lab data makes up more than half of a patient’s electronic health record, the LIS is likely to play some role, particularly if clients demand it.

|

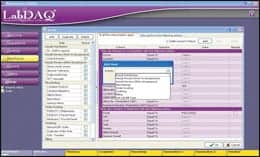

| LabDaq Rules |

|

| LabDaq Data |

|

| LabDaq Recon |

“We’re beginning to get questions about patient access to the data, and we are already working with Google and Microsoft, discussing the integration opportunities and capabilities of each,” says Curt Johnson, vice president of sales and marketing for Orchard Software Corp in Carmel, Ind. Having patients interact directly with the LIS is unlikely, but laboratory systems may be required to integrate with systems that offer this service, whether it be that of a third party, an insurance company, or even an in-house site.

“We have had some clients that have developed their own patient portals. It gives them branding and uniqueness,” Flora says.

Interface with Performance

Additional ways for a clinical laboratory to stand out include improving performance, which can be measured in terms of patient safety, efficiency, and/or revenues. The LIS was designed to help achieve these goals, in part by reducing the manual involvement of technologists.

“As facilities implement EMRs, they realize the results need to get from the lab to the EMR. Without an LIS, these results are typically entered manually, which is very time consuming and increases the risk for erroneous results to get into the EMR,” Laughlin says.

Some LIS programs have added safety features that go beyond data entry, such as patient identification verification, specimen tracking, and an HL7 reconciler that helps to validate patient results. “We believe the lab can play a very large part in the type of patient safety initiatives that are typically accomplished at the bedside and typically by care providers, such as nursing,” Hakim says.

These functions may also apply in outreach modules, which are growing more expansive to keep up with the increase in laboratories undertaking or expanding an outreach effort. “Many of our customers run very successful laboratory outreach programs, but when we looked at what the market needs were for laboratory outreach, what we realized was that there is a need for proactive customer service,” Hakim says, citing LIS features such as courier and specimen tracking that can help to meet this demand.

These safety functions often do double time as productivity enhancers. Fewer errors and less hands-on time enable laboratory technologists to apply their skills where they are most needed. “For managers to be able to see at a glimpse where the samples are coming from, how many the lab is going to get, and when it is going to get them helps them plan their work in the future much more efficiently,” Flora says.

Productivity tools remain a continued focus for many LIS systems. “Labs are, more than ever, looking for ways to run more efficiently and profitably,” Laughlin says, noting that many clients employ rules to achieve these objectives. They can be used to assist with routing (such as send-outs, per insurance company requirements), critical results, and reimbursements.

To track new LIS products, bookmark our website. |

Productivity can also be measured and enhanced with business intelligence and reporting. “The ultimate goal is to improve the care that the patient receives, and metrics have to be part of that,” Feist says. Facilities will want to determine the success of initiatives, the impact on patient care, and the effect on the bottom line. Effective business intelligence solutions enable this analysis to be accomplished in real time.

“Instead of asking how we did last month, we can ask how are we doing right now and what can be done today to ensure I meet my goals,” Feist says. The LIS can help to answer those questions and implement the answers.

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for CLP.

More Molecular

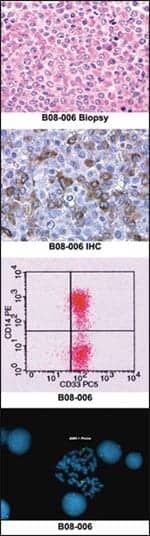

“From an LIS point of view, anatomic pathology and molecular are the fastest-growing areas of the laboratory,” says Curt Johnson, vice president of sales and marketing for Orchard Software Corp in Carmel, Ind. In many clinical laboratories, automation of molecular and anatomic pathology processes is not complete, and in some, it has not even begun, but more and more are aiming for this objective.

The challenges have existed not only in the analytics but in how to store and interpret the data digitally. It needs to be intermingled with results from the other laboratory areas, but molecular and anatomic pathology data is significantly different from what has formerly been managed by a LIS.

“[The information] includes images. It includes text. It includes, potentially, graphs and treatment protocols and lots of data depending on the type of molecular testing you are doing. And it all has to be accommodated by the LIS and, in some cases, integrated into the EMR,” Johnson says.

How this information will converge is still being fleshed out. Most LIS systems are developing a molecular module or improving an existing one. All the vendors CLP spoke with for this story mentioned this growing area as one that is a major focus.

Some in the industry expect that as the laboratory and these modules evolve, the LIS will take on a radically different structure, and even though some vendors have an idea of what this looks like, no one is yet ready to share. “It’s not too early to say. It’s too early to let our competitors know,” one source says.

—RD