“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrowmindedness” –Mark Twain

By Chris Wolski

Summary: Following a People-to-People trip to Cuba, the author gained a more nuanced view of the Cuban healthcare system, recognizing its strengths in universal access and preventive care despite challenges like resource and personnel shortages.

Takeaways:

- Universal Access and Preventive Care: Cuba’s healthcare system emphasizes universal access to care free of charge, with a strong focus on preventive medicine and door-to-door health monitoring, showcasing a commitment to public health.

- Challenges and Resilience: Despite its strengths, Cuba faces significant challenges such as resource shortages exacerbated by the U.S. embargo and the ongoing emigration of personnel mainly to the U.S. Despite these and other challenges, dedicated healthcare professionals continue to provide essential services.

- Potential for Development: Cuba’s biotechnology sector shows promise despite limitations, having developed vaccines and medical tests, albeit hindered by material shortages. There’s potential for growth with improved resources, offering lessons in resilience and innovation.

Having just returned from a People-to-People trip to Cuba (a program licensed by the U.S. Treasury Department), I have come away with a much different conception of the island nation. No Cold War boogeyman, Cuba and its people are energetic, resilient, hardworking, open-minded, and proud.

This cultural trip, which I took through UCLA, gave the unique opportunity to interact with a host of regular citizens and professionals, among them physicians.

And while there is no question that the Cuban healthcare system is under-resourced and has its flaws—its fundamental premises and organization has virtues that are worth exploring and perhaps even adopting with a U.S. flavor.

Cuban Healthcare: The Theory

Before you accuse me of stooging for Cuba, I want to make it clear that the country’s equalitarian system as it stands is not sustainable, as the growing entrepreneurial class is demonstrating. Was there propaganda in the presentations I attended—of course. But was there truth as well—I think so.

In theory, the Cuban Healthcare system has three operating principles:

- Universality, that is healthcare is available to all

- Free of charge

- Accessibility to every level of care when it’s needed—in theory there is no referral system

The extension of healthcare beyond urban centers to the underserved countryside was one of the twin pillars of the 1959 revolution (the other an aggressive literacy campaign). This required new doctors to serve at least two years in rural settings, a practice that carries on to this day.

According to Intensive Care Specialist and Bio-Ethicist Alberto Roque, the focus of Cuban healthcare is at the primary care level with prevention as the goal. Diagnostic testing is a part of this care, which is provided through local community health centers (serving a few hundred people) and door-to-door visits. For example, once a new mother goes home with her baby, she is visited daily by a doctor or nurse for a month to monitor the newborn and the mother. More advanced testing is provided at hospitals.

Roque noted that this type of door-to-door doctoring—along with Cuban-developed diagnostic tests and vaccines—was critical in limiting the number of official COVID deaths during the pandemic to only 9,000 out of a population of about 10 million.

Cuban Healthcare: Today

However, today’s Cuban healthcare system is definitely struggling. The ongoing U.S. embargo, which makes it difficult at best to import medical equipment and raw materials, along with the effects of the pandemic, and medical bureaucracy have resulted in both personnel (13,000 doctors have left Cuba post-pandemic) and material shortages.

Doctors and nurses work long hours with few resources and for low pay. Access to testing and treatment is eroding as is quality, overall, because of these factors.

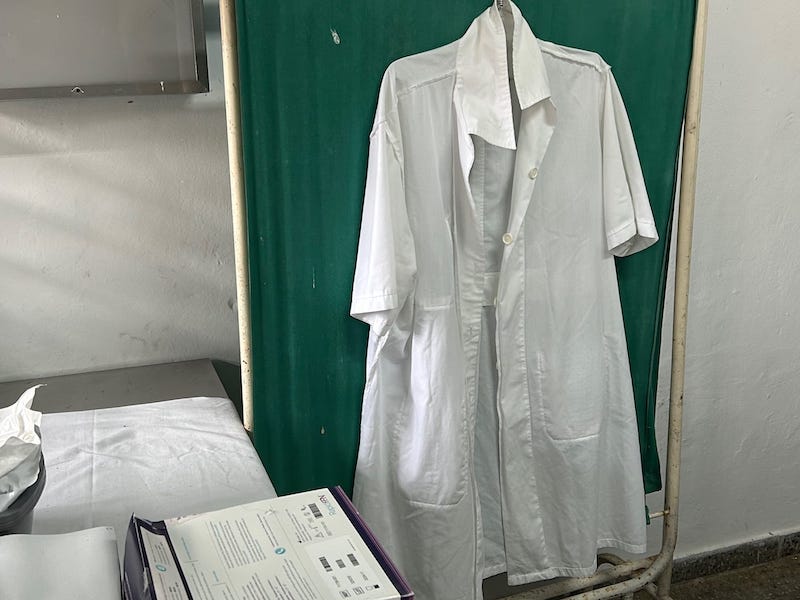

That doesn’t mean these doctors and nurses aren’t dedicated. We met a rural physician, Dr. Osviel, whose office was as basic as a school nurse’s, but it was clear that he was committed to providing in-office and door-to-door care and had the expertise to do so.

Parallels

No matter the expert—medical professional, social scientist, musicologist, ex-diplomat, et al—one thing that struck me was how much our two countries have in common. And this is particularly evident in the parallels related to healthcare.

Among the health problems facing Cuba, are:

- A growing obesity crisis

- A large population with diabetes

- An aging population

- A falling fertility rate

Add to it shortages in personnel and resources along with eroding accessibility as discussed above—and you have two systems that are experiencing many of the same pressures, though often for very different reasons. But the results are the same—poorer health for the patient and society as a whole.

Cuban Healthcare: The Potential

If there’s one ongoing thought I had throughout my trip, it was this: Cuba is a country of incredibly pent-up potential.

And once that potential is released it’ll be something to see I think. The healthcare sector, in particular, is poised to provide the biggest benefits to Cuba. BioCubaFarma, the country’s state-run biotechnology concern, constrained as it is by material and personnel shortages has developed neonatal, cardiovascular, and COVID tests, along with a vaccine for lung cancer (which is being trialed at Buffalo, NY’s famed Roswell Park cancer center—an example of the dizzying array of gray zones and gaps in the embargo, which allows critical touchpoints among our countries—providing examples of what could be).

As former diplomat turned professor and entrepreneur Camilo Garcia Lopez-Trigo told us about Cuba’s biotechnology sector: “We have the means but not the raw materials.” We’ve seen what Cuban biotechnology looks like without resources—imagine it with resources.

The country also does something, in spite of its difficulties, that is rather extraordinary. It exports its healthcare in the form of medical personnel. For example, Cuban physicians were in high demand during COVID providing care in rural areas of Italy and Spain—places local doctors didn’t want to serve, according to our lecturers. Dr. Osviel spent several years in the far east before returning to his hometown of Las Terrazas (population ~800) to care for his friends and neighbors.

From a purely economic perspective—it seems that there’s both a potential market and untapped resource of talent that is being neglected at our peril.

What Can We Learn?

I, of course, only saw a very surface level of the Cuban healthcare system. And, like ours, it can’t be summarized in just a few hundred words—but I’ve come away with a greater appreciation of what a stressed but resilient system run by dedicated professionals looks like.

And more importantly I think there are a few things we can learn from it. Functionally, the better ratio of doctors to patients (I read a statistic before my trip that it was 1:200; Dr. Osviel’s patient load was closer to 1:400), and the emphasis on door-to-door visits and prevention is something we could and, I think, should strive for. The service component for new doctors was also very intriguing to me. New doctors basically work off their “debt” to society and get practical training. We have a much smaller version of this with the U.S. military healthcare system (we coincidentally had a retire U.S. military doctor on our tour who attested to this). Expanding it to a civilian medical corps could help eliminate the crushing debt many young doctors face while helping to cover underserved areas. We may not get to the 1:200 (or 1:400) ratio, but it could be a formula to at least alleviate shortages and encourage more young people to become doctors, nurses, and, yes, laboratorians.

Now it can be rationally argued the equalitarian structure and lack of a profit motive in the state-funded system makes it unsustainable, and that is certainly evident and supported by some of the experts I met. However, as the public reaction to the assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson (which was appallingly grotesque) illustrated, the U.S. profit-based healthcare system has its own significant flaws—including a lack of access and ruinous costs for the insured.

Ultimately, it’s not an either/or proposition we’re facing. I think what I took away most is that there are lessons we can learn–positive and negative from the Cuban healthcare system. But this means, I think, we need to create space for discussion, trading ideas, and even having disagreements. Just like the U.S., Cuba isn’t just one thing—but many at once—and from my experience breaking down the barriers between us clearly will be a boon for both our countries and our health as well.

Chris Wolski is the chief editor of CLP.

Featured Image: The office of Dr. Osviel, one of two physicians serving the town of Las Terrazas, is basic, reflecting the lack of resources in the Cuban healthcare system. Photo: Chris Wolski