Liquid-based cytology with HPV cotesting improves cervical cancer screening

By R. Marshall Austin, MD, PhD

The general consensus among professional medical associations is that cervical cancer screening should be performed using liquid-based cytology (LBC) Pap and human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting. As shown in previous studies from around the globe, cytology adds significant value to cotesting. However, some analyses have called this approach into question and argued that cytology adds little to cervical screening efforts, prompting additional discussion on the contribution of cytology to screening protocols.

A recent US analysis has shown that the contribution of cytology to cotesting can be greater than has been revealed in previously published reports. The difference results in large part from the fact that the latest analysis used results obtained using optimized LBC, whereas the largest analyses questioning the value of cytology were based largely on cytology results obtained using conventional Pap smears, which are today rarely used to screen women.

It is the position of this article that the contribution of cytology in cotesting is directly proportional to the quality of the test used and of the lab performing and analyzing the tests. In other words, any assertion that cytology does not add substantially to cervical cancer cotesting may simply be a reflection of suboptimal cytology analysis and the use of out-of-date testing methods.

Studies and Guidelines

HPV and LBC cotesting is the recommended method for cervical cancer screening, according to guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and joint guidelines issued by the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology.1,2

Despite these recommendations, several analyses using data from testing performed at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) have concluded that HPV testing more reliably detects precancerous conditions and cancers than does cytology, and that cotesting does not detect enough additional cases of cancer or precancer to warrant routine use.3

However, these analyses of Pap testing as part of cervical cancer screening employed testing methods that differ from current standard practice in two respects.4 First, KPNC had long utilized conventional Pap smears, which have been largely supplanted by LBC Pap testing.5 Second, testing was performed using separate samples gathered for the HPV and Pap testing rather than by the single-sample, from-the-vial approach recommended by FDA for use in clinical trials.6 As a result, the analyses utilizing KPNC data probably underestimate the contribution of cytology to cervical cancer screening, and do not reflect the best data available to guide recommendations for screening in clinical practice. Unfortunately, these analyses continue to influence decisions about testing.

In particular, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued updated cervical screening recommendations that women aged 30–65 years have three screening options: a Pap test every 5 years; HPV testing every 3 years; or cotesting with the two methods.7

USPSTF decided not to prioritize combination testing based on several conclusions that may be supported by the Kaiser data but do not reflect optimal cytology practice. First, the Kaiser data suggest that there are “no clinically important differences between LBC and conventional cytology.” Second, the Kaiser researchers conclude that HPV alone is more sensitive than cytology alone for detecting precancerous abnormalities. And third, Kaiser analyses suggest that combination testing leads to the greatest number of false-positive test results and follow-up procedures, which are the primary potential harms of cervical cancer screening.8

By contrast to the reports based on KPNC data, a single 2016 analysis conducted by Quest Diagnostics using LBC testing in more than a quarter of a million women found that combination screening offered greater sensitivity when compared with either HPV or LBC alone.9

The new analysis described in this article was performed using results from optimized LBC resembling what is currently in broad clinical use today instead of older methods no longer widely used. The results corroborate the Quest Diagnostics findings and help confirm the professional community consensus that cytology and HPV cotesting utilizing LBC is the optimal method for cervical cancer screening.

Methods

This study analyzed cervical screening data collected at Magee-Womens Hospital (MWH) at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) between January 2005 and August 2017. The MWH-UPMC database included cervical screening test results obtained using widely used, FDA-approved LBC and from-the-vial HPV (hrHPV) testing methods.

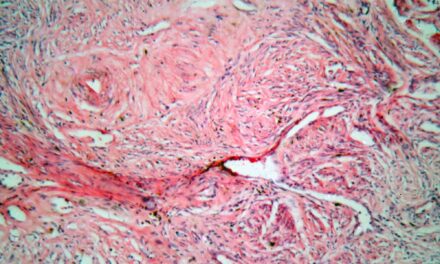

Figure 1. Microphotograph of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), indicating that the cervical cells show changes that are mildly abnormal.

Abnormal (that is, ‘positive’) LBC results included any Pap test reporting epithelial cell abnormalities classified as atypical squamous cells of underdetermined significance (ASC-US) or as a more severe abnormality (Figure 1).

The MWH-UPMC database included 300,800 cotest results from 186,000 women. Follow-up histopathological evaluation of cervical tissue samples from 66,045 women with cotest results diagnosed 129 invasive cervical carcinomas and 632 high-grade cervical intraepithelial lesions (either cervical intraepithelial neoplasm 3 [CIN3] or adenocarcinoma in situ [AIS]). Results for LBC alone, HPV alone, and HPV/LBC cotesting were compared in these women. Two-sided P values for comparisons of cytology and HPV tests were based on Z scores.

Results

Table 1. LBC-based Pap, HPV, and cotesting results preceding invasive cervical cancer diagnoses, overall and by cancer type. ADC = adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma; HPV = human papillomavirus; Pap = Papanicolaou test; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma.

Invasive Cervical Cancer. There were 198 cotests preceding the 129 invasive cancer diagnoses (Table 1). Of these preceding cotest results, 76% were HPV positive, 83.3% were LBC positive, and 89.4% were either HPV or cytology positive. Thus, cotesting resulted in 6.1% more positive results prior to an invasive cervical cancer diagnosis compared with LBC alone, and 13% more compared with HPV testing alone. Cotesting and LBC results (but not HPV results) were each more likely to be positive prior to a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) than an adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma (ADC) diagnosis (Figure 2).

As a component of cotesting, LBC was positive significantly more often than HPV testing before a diagnosis of SCC (92.7% versus 77.1%; P = 0.0025). In fact, the inclusion of HPV during cotesting did not add much to the positive test rate (1.1% more positive results than with LBC alone).

Figure 2. Microphotograph of a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), a squamous cell abnormality associated with human papillomavirus (HPV).

LBC results were also negative prior to an SCC diagnosis significantly less often than were HPV results (1% versus 16.7%; P = 0.0025), suggesting higher negative predictive value. Positive and negative rates for HPV and LBC prior to a diagnosis of ADC were similar, and it was for these diagnoses that cotesting with cytology and HPV testing instead of using one test or the other conferred the greatest advantage.

Precancerous Abnormalities. One thousand cotest results preceded 632 diagnoses of CIN3 or AIS. Positive results were obtained with 86.7% of HPV tests, 91.0% of LBC, and 93.9% of cotests that preceded a precancerous diagnosis (Table 2). Cotesting resulted in 2.9% more positive results prior to a precancer diagnosis compared with LBC and 7.2% more compared with HPV testing.

Due to the large sample size of precancerous test results, these differences were as substantial as the difference observed with invasive cancer diagnoses—or more so. Consistent with the invasive cancer findings, each testing modality was more likely to be positive prior to a diagnosis of CIN3 (the precursor of SCC) than prior to a diagnosis of AIS (the precursor of ADC).

As a component of cotesting, LBC results were positive significantly more often than HPV testing overall (P = 0.0023) and prior to a CIN3 diagnosis (92.7% versus 77.1%; P = 0.0025), but not prior to an AIS diagnosis. Negative LBC findings were much less frequent than negative HPV findings, both overall (2.9% versus 7.2%) and before an AIS diagnosis (2.1% versus 6.6%), again supporting a greater negative predictive value.

Table 2. LBC-based Pap, HPV, and cotesting results preceding precancer diagnoses, overall and by specific histopathology (CIN3/AIS). AIS = adenocarcinoma in situ; CIN3 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3; HPV = human papillomavirus; Pap = Papanicolaou test.

The Impact of Test Interval on Results. Cotesting results obtained less than 12 months prior to cervical cancer or CIN3/AIS diagnoses were more likely to be positive (HPV positive and/or cytology positive) than cotesting performed at least 12 months before the same histopathologic diagnoses (Table 3). The likelihood of false test results prior to a positive invasive cancer or precancerous diagnosis was much more likely when testing was performed at least 12 months before the diagnosis. For precancerous findings, any positive finding with LBC, HPV testing, or cotesting was strongly predictive of a subsequent positive diagnosis. Negative findings were followed by a positive diagnosis very infrequently.

When considering the individual testing methods, LBC results were more likely than HPV results to be positive prior to either cervical cancer or cervical precancer diagnoses, and this was the case when testing was conducted less than 12 months or at least 12 months before a cervical cancer or CIN3/AIS diagnosis. However, differences between LBC and HPV testing were only significant for precancer diagnoses, due to the much smaller sample size for the cancer diagnoses comparison.

Table 3. LBC-based Pap, HPV, and cotesting results preceding precancer diagnoses preceding invasive cervical cancer or cervical precancer diagnoses, by time before diagnosis (less than 12 months versus at least 12 months). AIS = adenocarcinoma in situ; CIN3 = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3; CxCa = cervical cancer; Pap = Papanicolaou test; HPV = human papillomavirus.

Discussion

In this study, the contribution of cytology to cotesting for cervical cancer was greater than in previous analyses, which evaluated KPNC data obtained using outdated testing modalities. In the study, 89% of all cervical cancer diagnoses and 94% of all precancerous diagnoses were preceded by positive results for either LBC or HPV testing.

While the inclusion of HPV in the cotest panel did not substantially increase the positive rate for SCC, cotesting allowed for a substantially higher rate of positive findings prior to ADC findings, which strongly supports the use of both tests as a means of identifying at-risk patients.

Notably, substantially lower percentages of cancers (70%) and precancerous conditions (84%) were preceded by positive findings on both the LBC and HPV tests. This finding highlights the fact that the tests are not redundant, but complementary. Cervical cancers or precancerous abnormalities are more likely to be captured by one test or the other than they are by either test alone.

Of the two cotests, LBC alone was more sensitive than HPV testing alone for both cervical cancer diagnoses and identification of precancerous abnormalities. In the cancer analysis, the superior sensitivity of LBC over HPV testing was most apparent prior to a diagnosis of SCC, which is easily the most prevalent form of cervical cancer.10,11 This finding suggests that, contrary to the KPNC analyses, optimized LBC can in fact be the more sensitive individual component of combination screening. There were far fewer diagnoses of cervical cancer or precancerous conditions after a negative LBC test than after a negative HPV test, suggesting potentially improved specificity as well as sensitivity. Additional evaluations to verify the bias-adjusted sensitivity and specificity of cotesting are under way.

The present study also speaks to the optimal time for testing. Specifically, there was a reduction in sensitivity for LBC, HPV, and cotesting when the interval after the test was increased. However, this was less apparent with LBC than with HPV, and even less apparent with cotesting compared with either LBC or HPV alone. Such a decline in sensitivity over time across all tests raises serious questions about the suggestion that the interval between screenings should be extended from 3?5 years to 5?10 years.

The superior results obtained in the present analysis compared with previous analyses were due primarily to the fact that cytology was performed using modern methodologies for LBC Pap testing, which when performed optimally offers advantages over the conventional Pap smear. LBC allows for increased harvesting of cells from the Pap collection device and for immediate wet fixation. As a result, cytotechnologists have better samples from which to work and more time to review each slide. These methodologic advances, and the improved test sensitivity they promote, allow for detection of enough additional cancerous and precancerous cases to warrant cotesting.

By contrast, an analysis using KPNC data concluded that a cotesting strategy using a conventional Pap smear would identify “at most” 5 additional cancers per million women. If this were true, then it would be reasonable to conclude that additional positive findings produced by cotesting (beyond the 5 per million women) would largely be false-positive results. Such false-positives would result in an increased frequency of unnecessary invasive procedures (colposcopy and biopsy) without a corresponding increase in cases prevented or treated in a timely fashion. According to USPSTF, false-positives and unnecessary procedures can be included among the chief harms of cervical cancer screening.

However, based on the present analysis, the substantial number of additional accurate diagnoses obtained with LBC/HPV cotesting would justify the additional costs of multiple tests and increased numbers of procedures. In short, cotesting would be in line with what the public wants: the maximal possible protection against cervical cancer. Most major health organizations agree with this position. And, again, negative findings during cotesting can allow for greater confidence in excluding many patients from intrusive follow-up.

Conclusion

The present analysis helps confirm that, in fact, a preferential recommendation of LBC/HPV cotesting is warranted. It is to be hoped that this recommendation will soon be uniformly issued across health organizations, including the USPSTF.

Patients frequently refer to the USPSTF site to obtain guidance on important health decisions, and in many cases the organization provides sound advice and performs an admirable service. However, with respect to cervical cancer screening, their recommendations do not reflect the most recent, reliable evidence. Consequently, health care providers faced with a choice of testing methods would do well to choose LBC/HPV cotesting and recommend it to their patients. In doing so, they will be following the current evidence-based recommendations of most medical societies, and significantly reducing the risk that cervical cancer or precancerous conditions in their patients escape detection.

Marshall Austin, MD, PhD, is a professor of pathology at Magee-Womens Hospital, where he also serves as medical director for cytopathology and staff pathologist in gynecologic and breast surgical pathology. For further information contact CLP chief editor Steve Halasey via [email protected].

References

- Committee on Practice Bulletins, Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e111–e130; doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000001708.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(3):147–172; doi: 10.3322/caac.21139.

- Castle PE, Kinney WK, Cheung LC, et al. Why does cervical cancer occur in a state-of-the-art screening program? Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):546–553; doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.06.003.

- Austin RM, Onisko A, Zhao C. Enhanced detection of cervical cancer and precancer through use of imaged liquid-based cytology in routine cytology and HPV cotesting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150(5):385–392; doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqy114.

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV-positive and HPV-negative high-grade Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S50–S55; doi: 10.1097/lgt.0b013e3182854282.

- Schiffman M, Kinney WK, Cheung LC, et al. Relative performance of HPV and cytology components of cotesting in cervical screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(5):501–508; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx225.

- Draft recommendation statement: cervical cancer, screening [online]. Washington, DC: US Preventive Services Task Force, 2017. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/page/document/draft-recommendation-statement/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed April 16, 2019.

- Gage JC, Schiffman M, Katki HA, et al. Reassurance against future risk of precancer and cancer conferred by a negative human papillomavirus test. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8):pii:dju153; doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju153.

- Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, et al. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(5):282–288; doi: 10.1002/cncy.21544.

- Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, Muñoz N, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(1):63–73; doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600688.

- Chiang YC, Chen YY, Hsieh SF, et al. Screening frequency and histologic type influence the efficacy of cervical cancer screening: a nationwide cohort study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56(4):442–448; doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.01.010.