In a study that could have a significant impact on how disease outbreaks are managed, researchers at the University of California, Davis, and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) have sequenced and analyzed genomes from Shigella sonnei bacteria associated with major shigellosis outbreaks in California in 2014 and 2015.

The results offer new insights into how the bacteria acquired virulence and antibiotic resistance genes, as well as the California strains’ relationships to other strains around the world. This was the first major, whole-genome study of S. sonnei strains found in North America. The research was published in the journal mSphere.1

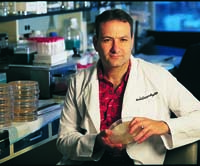

“If you have an outbreak and you want to know what is causing a particular problem, like antibiotic resistance, sequencing the genome can identify the genes involved,” says Jonathan Eisen, a UC Davis professor of medical microbiology and immunology, and evolution and ecology, and a collaborator on the study. “Eventually, we should be able to sequence whole genomes of bacteria to support patient care.”

One of four Shigella species, S. sonnei is responsible for most shigellosis outbreaks and can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal problems. Each year, shigellosis causes around 500,000 infections, 6,000 hospitalizations, and 70 deaths in the United States.

Led by Vishnu Chaturvedi, director of the microbial diseases laboratory at CDPH, the investigators sequenced the genomes of 68 isolates, including samples from the recent California outbreaks and historical strains from California, Asia, and elsewhere. They also tested for antibiotic resistance.

The team found two clusters in these outbreaks: one that primarily struck San Diego and the San Joaquin Valley, and one more localized to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Shigellosis is a diarrheal disease caused by a group of bacteria called Shigella. Photo courtesy US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The San Diego/San Joaquin strain has been in California since at least 2008. However, some of the isolates had been infected with a bacteriophage (a virus that attacks bacteria) that carried a Shiga toxin (STX) gene found in the more virulent S. flexneri and S. dysenteriae. Finding this gene helped explain why the recent outbreak had been so severe.

“Shigella sonnei bacteria normally cause a relatively mild disease and are not known to produce Shiga toxin,” says Chaturvedi. “The toxin gene was most likely acquired by Shigella sonnei via genetic exchanges with E. coli and other Shigella species. Discovering a functional toxin gene provided a partial explanation for the severity of illness.”

By contrast, the strain that hit San Francisco lacked STX but contained genes that gave it resistance to the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics. The fluoroquinolone-resistance genes were similar to ones found in strains from Southeast Asia. These findings provide important clues to the strains’ origins.

“We know these movements of DNA can be important for the spread of antibiotic resistance, virulence, and pathogenicity factors,” says Eisen. “Having the genome data from outbreaks allows us to try to figure out what happened.”

The researchers believe similar studies might ultimately benefit patients. Understanding a pathogen’s genetic variants could inform antibiotic choices and even help improve hospital procedures.

“If you can show that the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes came in response to some kind of treatment, you would certainly think about isolating people who were receiving that treatment, potentially sampling them more often, or even changing treatments,” Eisen says.

Before that can happen, genomic sequencing must become a routine part of the nation’s pathogen-surveillance model.

“We need to be sequencing the genomes of every organism that causes infection across the country,” Eisen says. “It doesn’t cost much and can be done in a relatively high-throughput manner. If we want to have an idea if a new outbreak is out there, or if that outbreak has a new toxin or resistance genes, that’s how we’re going to do it.”

The research was funded with grants from the California Department of Public Health.

REFERENCE

- Kozyreva VK, Jospin G, Greninger AL, Watt JP, Eisen JA, Chaturvedi V. Recent outbreaks of shigellosis in California caused by two distinct populations of Shigella sonnei with either increased virulence or fluoroquinolone resistance. mSphere. 2016;1(6):e00344-16; doi: 10.1128/msphere.00344-16.