New survey results show strong support for this standby of cervical cancer screening

By DaCarla M. Albright, MD

Cervical cancer screening with the liquid-based cytology Papanicolaou (Pap) test alone or in combination with the human papillomavirus (HPV) test has been shown to be effective in disease detection.1,2,3 Given the proven success of these methods, current screening guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and several other organizations recommend cervical cancer screening for women 21 to 29 years old with a Pap test every 3 years and for women 30 to 65 years old with a Pap test and HPV test (also known as cotesting) every 5 years.4

However, despite significant advances in early detection and treatment, cervical cancer remains a real threat to women. The rate of disease is no longer decreasing, possibly due in part to an increase in screening intervals in years past—which would indicate that proactive and thorough screening is still important to the overall well-being of women.

That’s why, as an ob/gyn, I’m encouraged that in today’s ever-changing environment for women’s health providers, there is

consistency in support for using the Pap test as part of cervical cancer screening, and the majority of healthcare providers (HCPs) and women consider cotesting to be important in managing overall health.6

How We Know This: Survey, Methodology, and Results

The National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH) and HealthyWomen (HW), a nonprofit women’s health organization, commissioned Cervical Cancer Today: A National Survey of Attitudes and Behaviors, through which women ages 25 to 65 years old nationwide (n = 1,000) and HCPs (n = 751), including nurse practitioners, ob/gyns, and primary care physicians nationwide actively treating patients, were surveyed online. The 2020 study sought to understand changes in attitudes, preferences, and practices over time, in comparison to a study conducted in 2015, to help guide future recommendations around women’s healthcare and cervical cancer screening.

Survey results make clear there is still strong support for the Pap test for women ages 21 to 29 years and cotesting for women ages 30 to 65 years because most HCPs claim to use the cotesting method to screen for cervical cancer in their patients.

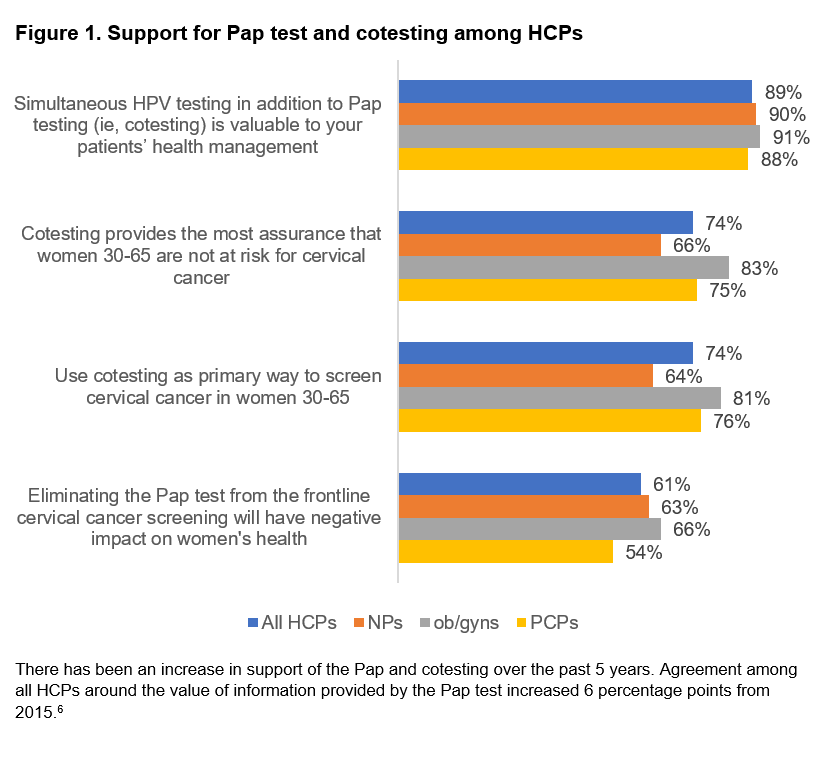

In the survey, 9 in 10 report they are likely to continue using cotesting for the foreseeable future, and 81% of ob/gyns say they use cotesting in patients between ages 30 and 65 years.6 It’s also worth noting these results mark an increase in support of the Pap and cotesting over the past 5 years (Figure 1).6 Importantly, less than 1% of HCPs said they screen using HPV screening alone.6

Most HCPs note in the survey they believe eliminating the Pap test would negatively impact women’s health, and the majority of patients (61% of HCPs; 68% of women) agree.6

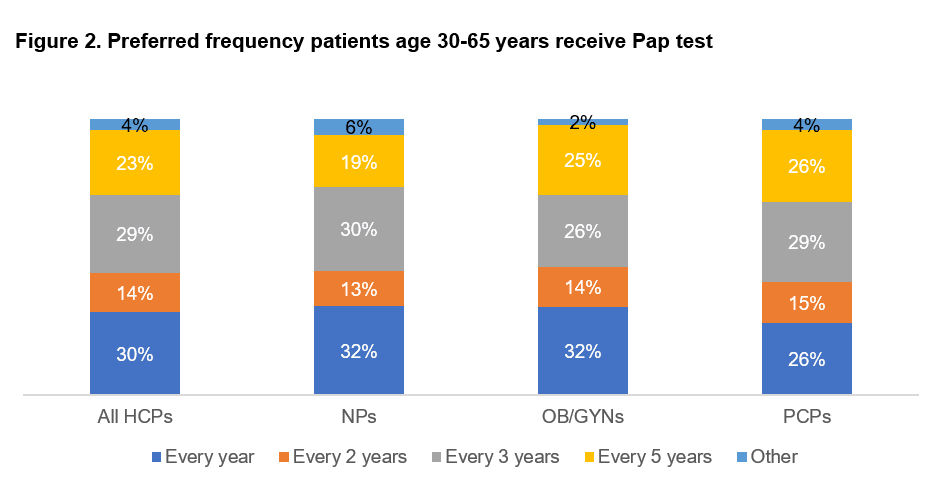

In fact, many women prefer cervical cancer screening more frequently than guidelines recommend. Although 57% of HCPs report discussing with patients that the guidelines do not recommend annual testing in most cases, 55% of women still prefer receiving the Pap test once a year, and many feel uneasy around the consensus guidelines that recommend a Pap test only every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years.6

If their HCP recommended receiving a Pap test every 3 years, 43% of women report they would be concerned.6 For additional context around preferred Pap test frequency, see Figure 2.6

The Discussion on Screening Today

These survey results reinforce that lab professionals are continuing to give the HCP community and their patients the screening methodologies they prefer and deserve, despite a debate taking place among organizations around cervical cancer screening.

When the American Cancer Society recently updated its cervical cancer screening guidelines for women at average risk,7 the most unexpected changes were the recommendations to begin screening at 25 years of age, as opposed to 21 years, and to remove the Pap test from frontline screening and rely on HPV screening alone. In response, a number of organizations released statements in support of the Pap test and cotesting for optimal cervical cancer screening, including the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP), the American Society of Cytopathology (ASC), and the College of American Pathologists (CAP), all of which are members of Cytopathology Education and Technology Consortium (CETC), as well as ACOG.8,9,10,11

The majority of associations, including CETC, support the work laboratories are already doing to ensure women’s health through cervical cancer screening and are skeptical of changes that might diminish the value of the Pap test and cotesting. Healthcare providers, too, have doubts around moving away from the current standard of Pap testing and cotesting, and they recognize the potential pitfalls of HPV testing alone (Figure 1).6

According to the survey, when it comes to HPV-alone screening, HCPs fear the possibility of

- More missed diagnoses (62%)

- More recommendations for colposcopies (61%)

- More positive diagnoses with no treatment options offered to patients (58%).

Research supports the fear that cases will be missed if only high-risk HPV tests are used for screening—up to 10% of invasive cervical cancers test negative for HPV, and up to 14% may be negative for high-risk HPV types covered by the tests. Additionally, 8.3% to 14% of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cases may also be negative for high-risk HPV.12,13 Screening with only an HPV test has proven less effective than cotesting, and in fact the largest real-world retrospective study found that one in five cases of cervical cancer were missed with HPV screening alone—that is approximately 2,400 women whose cervical cancer may not be diagnosed.14

The numbers above—10% to 14%, 8.3% to 14%—represent missed cases and disease risk at rates much too high for any women’s HCP to accept. These concerns and these statistics are why nearly all HCPs surveyed say they plan to continue using the Pap test as part of their cervical screening practices for the foreseeable future.6

What Does this Mean for Lab Professionals?

Cervical cancer is highly preventable with regular screening and follow-up, and the method by which cervical cancer screening is conducted matters—it matters to patients, and it matters to the HCPs and lab professionals who are our critical partners in screening, diagnosis, and treatment. The role of lab professionals as partners in cervical cancer screening remains key in preventing this cancer among women because ob/gyns like myself need strong collaboration with lab professionals to fully assess disease risk and the best path for each patient.

Lab professionals are doing valuable work that is supported by critical organizations including CETC and ACOG. Now is the time to reinforce support for all screening options available and continue to deliver on what providers and patients have expressly said they want—the full picture of cervical health through the Pap test and cotesting, which are necessary to detect more cases of disease and save more women’s lives.

DaCarla M. Albright, MD, is a practicing ob/gyn and professor with nearly 20 years of clinical experience ranging from prenatal care to gynecologic surgery. She is a member of the Women’s Health Advisory Council of HealthyWomen, a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and a member of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Her academic interests are strongly focused in medical education. Albright received her medical degree from the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, followed by a residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore in Maryland.

References

1. Austin RM, Onisko A, Zhao C. Enhanced detection of cervical cancer and precancer through use of imaged liquid-based cytology in routine cytology and HPV cotesting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150(5):385-392. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqy114.

2. Kaufman H, Alagia DP, Chen Z, Onisko A, Ausgtin RM. Contributions of liquid-based (Papanicolaou) cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cotesting for detection of cervical cancer and precancer in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154(4):510-516. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa074.

3. Ge Y, Christensen PA, Luna E, et al. Age-specific 3-year cumulative risk of cervical cancer and high-grade dysplasia on biopsy in 9434 women who underwent HPV cytology cotesting. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019;127(12):757-764. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22192.

4. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol.2016;128(4):e111–e130. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708.

5. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. NAACCR Fast Stats. Available at: https://faststats.naaccr.org/index.php. Accessed January 12, 2021.

6. Albright DM, Rawlins S, Wu JS. Cervical cancer today: survey of screening behaviors and attitudes. Women’s Healthcare. 2020;8:41-46.

7. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(5):321-346. doi: 0.3322/caac.21628.

8. American Society for Clinical Pathology. Release of the 2020 American Cancer Society cervical cancer screening guidelines. Available at: https://www.ascp.org/content/docs/default-source/get-involved-pdfs/istp_clinical_practice_guidelines_and_resources/cetc-society-posting—acs-cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines—final-8-20-20.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed January 12, 2021.

9. American Society of Cytopathology. Release of the 2020 American Cancer Society cervical cancer screening guidelines. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/cytopathology.org/resource/collection/75A4FB3E-BE73-4755-84EA-54214443AE0E/ACS_Cervical_Cancer_Screening_Guidelines_%e2%80%93_ASC_Response.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2021.

10. College of American Pathologists. Letter to the Director of Guideline Development Process at the American Cancer Society. October 15, 2020. Available at: https://documents.cap.org/documents/cap-response-to-acs-letter.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2021.

11. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. ACOG Statement on Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. July 30, 2020. Available at: https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2020/07/acog-statement-on-cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines. Accessed January 12, 2021.

12. Ge Y, Mody RR, Olsen RJ, et al. HPV status in women with high-grade dysplasia on cervical biopsy and preceding negative HPV tests. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8(3):149-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2019.01.001.

13. McCarthy E, Ye C, Smith M, Kurtycz DFI. Molecular testing and cervical screening: will one test fit all? J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2016;5(6):331-338. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2016.08.001.

14. Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, Austin RM, Rabin DS. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(5):282-288. Doi: 10.1002/cncy.21544.

Featured image: Squamous epithelial cells of human cervix under the microscope view. Photo © Puntasit Choksawatdikorn, courtesy Dreamstime.com (ID 183352409).