When a patient presents with the appearance of a respiratory ailment, the physician will typically order a number of laboratory tests to help rule in or rule out certain pathogenic entities. Is it infectious? Is it bacterial? Is it viral? The answer will help to determine the next course of action. Does the patient need antibiotics? Antivirals? Should the patient be isolated? Does the infection need to run its course?

“A negative result will mean something to the doctor as well as a positive result,” says Elliott L Rank, PhD, D(ABMM), director of scientific affairs/medical affairs for BD Diagnostics, San Diego.

“If the doctor knows the patient has a viral infection based on test results, that can be useful information for patient and/or parent counseling for the purpose of avoiding unnecessary antibiotic therapy,” says David Persing, MD, PhD, executive vice president and chief medical and technology officer for Cepheid, Sunnyvale, Calif. Being able to say with certainty that the infection is parainfluenza, for example, will carry more weight than claiming it is “likely a virus,” to which the response could be, “But it might be bacterial, right?”

“Studies have shown when you identify the causative agent of these respiratory infections, particularly in a hospital setting, then generally the patients are released sooner and are treated less frequently with inappropriate antibiotics,” says Jeremy Bridge-Cook, PhD, senior vice president of the assay group at Luminex Corp, Austin, Tex.

The information can also be used to properly cohort patients. “You don’t necessarily want someone with a bacterial infection sharing a room with someone with a viral infection because they’ll give their infections to each other, and they’ll both end up being worse off,” Bridge-Cook says. On a broader scale, isolation of contagious patients protects everyone from nosocomial infections.

Respiratory viral diagnostics, therefore, offer clinical value whether or not there is an available treatment for the identified infection. Used appropriately, the test can save money through improved care, shorter stays, and greater cost-effectiveness. Clinical value, however, is only the first support of a three-legged stool that determines a diagnostic methodology’s success.

The second is turnaround. “Is it a good test that will provide the diagnosis in a rapid time frame that is within a reasonable window to be able to decide on an action for that patient?” asks Gregory Bond, BD’s worldwide vice president of sales and marketing/BD Point of Care.

The third leg is cost. For a diagnostic to undergo widespread adoption, it requires reimbursement; the ability to generate revenue is even more advantageous. Any resulting cost savings are an additional bonus to the return or the bottom line.

In the area of respiratory viruses, however, no one methodology has balanced all the legs on that stool. “In my mind there is really no gold standard for the respiratory viruses, as yet,” Rank says. Although cell culture is used as the primary comparison method for product clearances in the United States, many health care institutions use molecular testing to confirm diagnoses from rapid methods.

“The method that’s been in use the longest, that is considered to be reliable and can always be fallen back upon, would be culture. If you’re looking, though, at the method that is considered the gold standard in terms of best performance for sensitivity and specificity, I would say that’s been PCR,” Bridge-Cook says.

BD Directigen EZ RSV is a rapid chromatographic immunoassay for the direct and qualitative detection of RSV antigen.

The Way of the Past

Despite the traditional use of cell culture as a gold standard, Rank notes that facilities outside of large academic institutions and reference laboratories no longer offer the technique. “You’ll find the overwhelming majority of institutions no longer have the capability or the capacity to perform cell culture,” Rank says.

Cultures have evolved over the years, with experts citing shell cultures as a prime example, but the processes continue to be long and involved, often requiring lengthy turnarounds (often multiple days), a significant footprint, experienced personnel, and hands-on attention. Each virus being tested typically requires its own unique set of conditions, from cell line to culture medium to incubation time.

As a result, “Many laboratories have decided to stop doing viral cultures as the mainstay of viral diagnosis. The whole emphasis of diagnostics has now shifted toward frontline use of molecular diagnostics, and that’s in recognition of the superiority of molecular methods for sensitivity and also for turnaround time,” Persing says.

The Way of the Future

Molecular diagnostic methodologies eliminate the need for conditions specific to the respiratory virus in question and are less complex than cultures. “[PCR] doesn’t really care what conditions the virus requires. All it cares about is whether it has DNA or RNA,” Persing says. RNA-based viruses will require a reverse transcriptase step; DNA is straight PCR.

Many institutions are, therefore, using molecular methods (whether commercial or laboratory-developed) to confirm and subtype diagnoses rather than cell cultures, making molecular a de facto gold standard. However, PCR is not perfect, either.

Currently, molecular methods incorporating PCR are rated at a higher complexity, requiring more skill and hands-on time to run. They are also more expensive, often necessitating a significant investment in analyzer technology. And they can take a few hours to turn around results, a problem for the physician who needs to make an immediate decision regarding medication, isolation, and other treatment actions.

In addition, the high sensitivity associated with PCR tests, while most often a plus, can result in the detection of residual virus, indicating the virus is present but at a point when it is no longer an issue. “Someone can be 2 weeks past the onset of symptoms, and there is enough residual nuclear material to test positive when, in fact, it doesn’t necessarily correlate back to the patient having the illness at that moment,” Bond says. Physicians, therefore, must consider the results against the timing of the patient’s presentation of symptoms.

Even so, many think molecular is the future’s gold standard for the diagnosis of respiratory viruses. Moderately complex methodologies are beginning to come on to the market, and vendors are focused on shortening turnaround times, increasing automation, and reducing complexity for future generations.

One for All

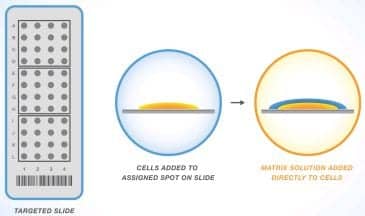

Luminex’s xTAG RVP provides results on multiple respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), arainfluenza, influenza, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus.

Luminex has submitted an application to the FDA for its faster follow-up to its xTAG Respiratory Viral Panel (RVP), the xTAG RVP Fast, and is working with the organization on clearance. Both xTAG RVP and xTAG RVP Fast provide results on multiple respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza, influenza, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus.

Multiplexed tests represent the future even more than PCR as they can provide more information from one sample, simultaneously. However, these tests also tend to be found in larger health care institutions, at the moment, and can be regulated in ways that may limit use.

Results should be reported based only on what the physician ordered, not the scope of the test’s capabilities. Results of multiplex panels may sometimes generate additional data. “There are rules about the lab being able to report results that weren’t ordered by the doctor,” Bond says.

The physician, therefore, needs to approach the diagnosis efficaciously. The initial emphasis is often placed on those conditions for which treatment decisions are clear, such as with RSV. “[For some respiratory infections], there are drugs available, and [in those instances], sooner is better than later. In fact, you could argue that if it takes more than on hour or 2 [to get results], it’s probably not worth testing because the patient will have left, and by the time the results are available, the symptoms may be resolved and the impact of the therapy is diminished,” Persing says.

Quick and Dirty

For this reason, rapid tests still play a vital role in the determination of respiratory viruses. “That’s really the basis for why the practice community has made so many sacrifices in test performance with the rapid antigen tests for flu. They’d rather have quick and dirty than slow and accurate,” Persing says.

Unfortunately, today’s rapid antigen tests, often based on a lateral flow technology, can be quite dirty. “They’re between 30 percent and 70 percent sensitive relative to molecular methods, and they have poor specificity as well,” Persing notes. False positives are a particular problem, occurring in the 5% range for most of these assays, according to Persing.

To stay current on respiratory virus testing products, visit our website often.

However, they are very fast, often delivering results within 15 minutes. They can usually be performed anywhere, do not require large or specialized equipment, and, when used properly, can be quite accurate. “If a specimen is of high quality, representative of the early stage of the disease, and taken early on in the course of the disease, the positive agreement should be very good compared to other methods,” Rank says.

After 72 hours from disease onset, the viral shedding has typically slowed and the rapid diagnostic can test negative, while the PCR says positive. Physicians must, again, consider presentation alongside results.

“Really, the ideal solution is to come up with methodologies that have the accuracy of molecular methods but with the turnaround of rapid tests, so the results are not only rapid and actionable, but they also are accurate. That’s sort of the holy grail for these respiratory virus infections,” Persing says. And that’s thinking positive.

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for CLP.