A senior medical director for Quest Diagnostics outlines how the pandemic impacted—and is continuing to affect—prostate cancer diagnostics and what this will mean for clinical labs now and in the near future.

By Chris Wolski

There’s little argument that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has impacted almost every area of our lives, and none more so than our health. While many patients have been—correctly—laser focused on being tested for COVID-19, they have been much less stringent in routine medical tests, such as prostate cancer screening, STI testing, and testing related to drugs of abuse.

Harvey Kaufman, MD, MBA, senior medical director at Quest Diagnostics, led a study for the company examining the impact of COVID-19 on prostate cancer screening and diagnoses. The results of the study are part of Quest Diagnostics Health Trends, which he has been involved with since it began in 2005 and now leads.

CLP sat down with Kaufman prior to the Omicron surge to discuss the findings of the study, how the pandemic impacted prostate cancer diagnostics, and about the future of diagnostic testing in general.

Kaufman’s answers have been edited for length and clarity.

CLP: You were involved in a study about how the pandemic impacted prostate cancer testing and how it went down—as did many other critical diagnostic tests—during the height of COVID-19. How much did these numbers drop and why was this critical?

Harvey Kaufman: A previous Quest Diagnostics Health Trends report published in JAMA Network Open highlighted the decrease in patients newly identified with different cancer types, including prostate cancer. The report found the decline in cancer diagnoses was greatest early in the pandemic, then rebounded through the second half of 2020 through 2021. Unfortunately, the rebound was not enough to account for the gap in care, and in most cases, diagnoses have not fully returned to pre-pandemic levels.

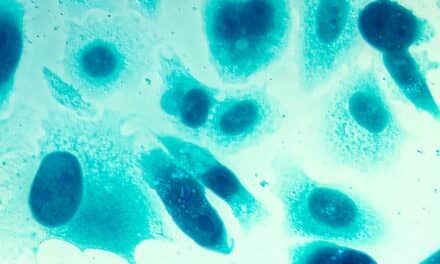

This new study published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics focused exclusively on prostate cancer, evaluated through both blood-based Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) testing (16.4 million) and prostate biopsies (49,000). In the early pandemic period (March-May 2020), PSA testing declined 36%, and subsequently (June-December 2020) increased to 4% above pre-pandemic levels. Prostate biopsies declined similarly (38%) in the early pandemic months but were still down 18% in June-December 2020 compared to pre-pandemic volume. We observe that the men most likely missing from care are younger and at early stages of the disease, though some advanced cancers likely remain undiagnosed, too.

The gap is critical because cancer didn’t pause during the pandemic. Routine screening and healthcare visits decreased, and many men have yet to re-engage with healthcare services. Although the study focuses on men and prostate cancer, the general observations apply to children, women, and almost all other healthcare services, as evidenced in the earlier JAMA Network Open study.

CLP: What was the proximate cause of the drop?

Kaufman: In the early months of the pandemic, most routine healthcare services were suspended to allow healthcare providers to focus on the urgency of COVID-19. As offices and services re-opened, many patients remained fearful of travel to healthcare offices and of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the causative virus for COVID-19. For many patients, regular visits for healthcare services were broken. One challenge, now, is to re-establish patient routines to visit doctors, so we can resume routine medical screening, diagnostic tests, and procedures.

CLP: What type of PSA testing are talking about specifically? Digital only or digital and PSA blood testing?

Kaufman: The digital rectal exam (DRE) is being used less frequently by primary care physicians, in part because of the small incremental value it adds to PSA testing and because most men find this part of the physical exam uncomfortable. In addition, the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not support routine screening with PSA testing. However, PSA testing volume (pre-pandemic) was not impacted much by the recommendations. Our study focused on just PSA testing (not on DRE), and we also looked at prostate biopsies.

CLP: What are the implications for both clinical labs and the overall continuum of care for just this one test type? In other words, what will be the long-term and short-term effects of how the pandemic impacted this decline in testing?

Kaufman: Again, cancer didn’t pause during the pandemic, so as patients with prostate and other types of cancers are ultimately diagnosed, some will present at more advanced states and require more aggressive therapies, and some will have worse outcomes, including death.

Clinical laboratories will accommodate increases in testing that may ensue. Likewise, healthcare facilities are likely to see increases in more advanced therapeutics including surgery, radiation, and drug therapies. The consequences will probably reverberate for the next decade, something that is particularly tragic given the tremendous progress against cancer we have made over the years, driving down mortality rates. This progress will be reversed for many years.

CLP: Can you put the prostate testing drop in context—how did this drop correlate to other basic diagnostic tests (e.g., diabetes, STI, hepatitis, etc.)?

Kaufman: We observed a slight decrease in pregnancy-related testing in 2020, with the 2021 decline closely aligned with the more gradual long-term decline. Most routine testing showed a similar pattern to what we observed for PSA testing. Sexually transmitted infection testing fell more so because younger people without symptoms were more likely to skip healthcare than older people and younger people with symptoms. Drug and substance screening fell most dramatically as treatment centers and resources have still not returned to pre-pandemic levels of support. The decline in healthcare services, including testing, continues to contribute to the sharp rise in drug misuse and drug overdose fatalities.

CLP: A lot of labs were overwhelmed with COVID testing. As numbers eventually drop, from your perspective, how well will labs be able to catch up with other testing? Is the ongoing COVID testing still causing logjams?

Kaufman: Laboratories prioritized COVID-19 testing but still maintained full support for the rest of their test menu. In mid-2020, we had a temporary shortage of swabs for other tests such as for chlamydia and gonorrhea when swab manufacturers focused on swabs for SARS-CoV-2 testing. Supplies have not been an issue since [Editor’s Note: This interview was conducted prior to the Omicron surge]. What we hear about now are shortages of medical technologists and other labor shortages affecting manufacturers, as we all see unfilled job positions in our communities. The labor shortage will be the primary challenge in maintaining laboratory services moving forward.

CLP: If there are logjams—are they only occurring in labs or are they being caused at other points along the treatment continuum, e.g., patients, doctor offices, insurance companies, etc.? Is there anything that clinical labs can do to help to alleviate any delays in testing, even if they aren’t the cause?

Kaufman: Physicians were busy pre-pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, their offices were addressing patients with COVID-19, COVID-19 exposures, SARS-CoV-2 testing, and vaccinations—all on top of their existing pre-pandemic busy daily schedules. Further, more healthcare professionals retired during the pandemic than expected compared to predictions if there had been no pandemic. Thus, there just aren’t enough physicians, physician assistants, or nurses available to deal with the pent-up demand for routine health services. Patients are waiting longer for appointments for non-urgent care. What this means is that whether it is men who will wait even longer to get a PSA test or prostate biopsy, or children and women for other tests, the delay in healthcare services and its effects will persist well into 2022.

CLP: There’s little doubt how the pandemic impacted testing as a whole. When do you think testing levels are going to get back to pre-pandemic levels, and what do you think that ongoing endemic COVID testing will do in terms of capacity? Will it continue to cause challenges for clinical labs?

Kaufman: Clinical laboratories will handle all the demands placed upon them. The demand will likely include ongoing SARS-CoV-2 testing and a slight decline in other testing until all patients are comfortable returning to routine healthcare and as physicians, physician assistants and nurses find ways to accommodate more patients. As dedicated laboratorians, we have always found solutions. It is expected that the staffing shortage will take several years to resolve even if we can expand training programs, reversing years of declining programs and trainees.

The key takeaway from our most recent study is that most diseases, especially cancer, didn’t pause during the pandemic. Working together with our colleagues in medicine, we will find ways to expand our reach to patients who have skipped or delayed care. As healthcare professionals who may have delayed routine care, we also need to re-engage ourselves with healthcare services and encourage family members, friends, and colleagues to do the same.

Chris Wolski is the chief editor of CLP.