With major testing/imaging technology providers Siemens, GE Healthcare, and Philips already in the headlines, is the dance to more full-service diagnostics under way? And if so, are IVD firms on every level wondering whether industry changes will be music to their ears or leave them out in the cold?

After the testing business merger between German-based corporate giants Siemens and Bayer, imaging leader GE Healthcare in January publicly announced plans to acquire laboratory testing and blood analysis business units from Abbott Laboratories for a price reportedly in excess of $8 billion.

-

- Siemens’ Immulite 2500 (top) and Advia 1800 (bottom)

But after 6 months of negotiations, in early July GE and Abbott abandoned the deal. In public announcements, officials from both companies said they were “unable to reach agreement on final terms and conditions.” But scrapping that deal may not mark the end of efforts by GE Healthcare to expand into IVD.

Analysts point out that boosting business in the diagnostics and health care segment generally makes business sense for GE, since profits from its health care segment are increasing at a faster clip than other corporate sectors combined.

Another merger bombshell hit in July when Siemens announced an agreement to acquire diagnostics company Dade Behring for $7 billion.

For clinical labs, the questions are many: What will be the impact of the marriage of imaging, in vitro diagnostics, and informatics? How will established clinical labs respond? How will the marriage advance patient care?

Early Health Model

Brian McKaig, director of public relations for GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, Wis, says his company considers IVD the “gateway” to diagnostics.

“GE Healthcare has a broad diagnostics business and is operating from a position of strength,” he says, when asked about the impact of his firm walking away from the Abbott buy. “There’s no change regarding GE Healthcare’s strategy; we remain committed to our vision of ‘Early Health’ and will continue to evaluate in vitro diagnostics opportunities that fit our Early Health strategy, pursuing growth through organic and inorganic means.”

McKaig says an expansion into in vitro diagnostics would complement GE’s existing positions in diagnostic imaging systems, including x-ray, magnetic resonance, ultrasound, and other imaging procedures that look at what is in the body to diagnose disease.

Addition of core laboratory diagnostics would enhance GE Healthcare’s ability to offer a broad range of medical tests and diagnostic instrument systems used worldwide to diagnose and monitor diseases by hospitals, laboratories, blood banks, and physicians’ offices.

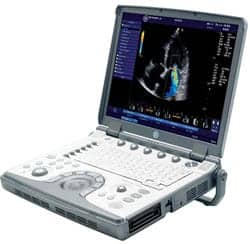

-

- GE’s Vivid E (top) and Signa HDx 3T (bottom)

Then there’s Netherlands-based Royal Philips Electronics NV. The firm’s medical systems group has been producing high-end technology x-ray and scanner equipment used by hospitals for many years. Now, with an aging US Baby Boomer population facing more chronic diseases, Philips, too, is increasing its profile in health care, if not diagnostics, by targeting the elderly with prevention devices such as the HeartStart Home Defibrillator, and LifeLine, a medical alert system.

Value of Combined Approach

The recent move by imaging companies into IVD is undeniably a trend, says David Okrongly, PhD, senior vice president, molecular business unit of Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY.

“At Siemens, we are bringing together two diagnostics companies—Bayer Diagnostics and DPC—and our efforts are right now focused on bringing together these two powerful product lines of immunoassay, informatics, and automation for our customers,” Okrongly says. “This year we will launch our first combined product: a work cell linking the Immulite immuno system and the ADVIA Chemistry system, and also roll out our product portfolio plan for the future.”

Siemens is also laying the groundwork for unlocking the value of a combined approach to in vitro and in vivo diagnostics, a move Okrongly predicts will have major impact in diagnostic workflow for patients and development of new biomarkers for earlier disease detection, as well as influence the development of new pharmaceuticals.

Okrongly says the biggest clinical labs saw the move by imaging firms into IVD coming.

“My personal opinion is that the activity of IVD companies being bought by imaging companies was anticipated by the big reference labs,” he says. “They must have been thinking for a couple years now about how they themselves might enter into the imaging market and provide integrated services for their customers. In the town where I live, there is a Quest phlebotomy center right next door to an imaging center. I wonder how many people make stops at both centers to manage their health and have to have duplication of their medical records, test results, insurance billing information, etc. I have no doubt that all this could be more efficiently managed by a single service-providing company.”

-

- More information on in vitro.

Okrongly says Siemens entered the IVD arena for very clear reasons: to improve workflow and overall efficiency of patient management by providing diagnostic solutions, including IVD, imaging, and informatics, that enable the physician treating the patient to achieve the best outcome possible.

“The long-term impact of these changes will be a greater awareness of the role that each diagnostic service plays in delivering the complete diagnostic picture of a patient in a timely way,” Okrongly says. “In order to realize these workflow and cost efficiencies, there will probably have to be changes in how departments are organized. But the skill and care that make someone a great radiologist or pathologist or laboratory technician will be an even more valuable asset in the future.”

Natural Application of Technology

Richard Friedberg, MD, PhD, chairman of the department of pathology at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass, oversees a 22-pathologist hybrid academic/private practice operation responsible for 50,000 surgical specimens, 90,000 cytology specimens, 6 million lab tests, and a major regional reference laboratory. Active on many College of American Pathologists committees, Friedberg is a professor and deputy chairman of the department of pathology at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston.

Friedberg sees as separate issues the momentum moving toward full-service diagnostics and increasing market clout eyed by such supervendors as Siemens and GE Healthcare.

He says the former is driven by business and technology, while consumers and providers are driving the latter. Friedberg says integration of in vivo and in vitro diagnostics is a natural application of technological improvements that allows for more rapid accumulation of data, which will then be interpreted and integrated into usable information to be delivered and provide value to consumers.

According to Friedberg, society has seen this transition before: A long time ago, someone created a mill that ran on water or animal power to grind grain. Later, that technology evolved into an engine running on oil, electricity, or gas.

“Now we have planes, trains, and cars running on engines, turbines, hybrids,” Friedberg says. “If you want to get from New York City to Chicago tonight, you’ll choose the method that gets you there safely and on time. How the airplane got in the air and stays up there is irrelevant to almost everyone other than a select few,” he says. “A completely separate question is why you needed to be in Chicago so quickly.”

Similarly, Friedberg says providers need usable information to make diagnoses, and they don’t care much about whether that information comes from technology using photons, radio waves, or chemical sensors—as long as the information is usable and reliable enough to make an accurate interpretation for the care of the patient.

“A completely separate question is whether obtaining that information sooner is usable for the benefit of the patient. Many diseases are better treated early. But treatment has its own effects—cost in terms of time, morbidity, angst, and opportunity that preclude full-time monitoring of everyone for everything,” he says. “Not all information is actionable and not everyone would want to know that they’ll be dead in 2 years from some untreatable horror.”

Any pressure from emerging supervendors will depend on the net gains from their integration and what actually can be implemented in improvements in patient care. “They’ll have to prove that part. If all they do is add data without adding information, then they have not added much at all,” Friedberg says.

He describes the marriage of in vivo and in vitro as a definitive step rooted in emerging technology. “Every business has the option of making it positive or fighting to hold on to mythology,” he says. “There will be costs associated with implementation, and there will be costs associated with delaying tactics and ignorance. Pick which ones you want and how you want to handle them.”

It is clear that in the long run, technology per unit gets cheaper over time. “We will be providing more care to more people at greater cost, but that does not necessarily mean a greater cost per person or more care per person,” Friedberg says. “If it’s not justifiable, it won’t last.” One example he cites is drug-eluting stents.

Friedberg’s advice to labs that have successfully concentrated on in vitro testing: Do what you need to do to provide the care you need to provide. “If you focus on testing only as a revenue source, then think about how you will handle the changing landscape. The tools will change, but the data derived and information delivered will also change. The bottom line is that the future is not in 19th-century technology of tanning dyes and horses.”

Too Soon to Tell

Gary D. Samuels, vice president, corporate communications, of the nation’s largest reference laboratory, Quest Diagnostics, Lyndhurst, NJ, says he believes it is too soon to draw any conclusions on how the recent Siemens acquisition will influence diagnostic testing in the future.

“What is clear is that the combination of Siemens/Bayer underscores the health care industry’s growing awareness of the importance of diagnostic testing in identifying and treating disease, including at the earliest stages.”

With more than 30 laboratories and 2,100 patient service centers in the United States performing more than 3,000 different tests, Quest Diagnostics covers the gamut from routine to esoteric. Its personal health testing, including gene-based testing, reaches more than 150 million patients a year.

Samuels says the diagnostics testing industry is a huge and remarkably complex market. “There are many opportunities for companies with different competencies to contribute to this market.”

Quest, like many others, is a customer of both GE and Siemens; hospitals and other lab companies are customers of Quest Diagnostics as well as GE and Siemens. Industry experts have long contemplated the value of bridging different technologies to improve health care. Since 2002 Quest has been addressing why greater convergence of diagnostic competencies and technologies is necessary for improving patient care and lowering health care costs.

While information technology is the foundation on which these companies work to bring data together so clinicians can make better decisions, using diagnostic tests to identify disease at an early stage may not always improve health outcomes, according to Joyce G. Schwartz, MD, vice president and chief laboratory officer at Quest.

An example: A patient whose heart disease results from his lifestyle choices, such as lack of exercise, will need to change certain behaviors to promote better health. “Yet, the industry increasingly understands that the path to better patient care begins in the earliest stages of disease, when treatment is more likely to be successful as well as cost-effective,” Schwartz says.

Samuels says Quest has been making its own business moves recently. Its purchase of AmeriPath extends Quest’s capabilities further, especially in the anatomic pathology area. This year’s acquisition of HemoCue strengthens Quest’s position in point-of-care testing.

The in vivo and in vitro combination brings benefits, says Schwartz. Example: A test called an integrated maternal serum screen for Down syndrome integrates results from a fetal ultrasound with biochemical laboratory results to provide a risk assessment of the fetus carrying an extra chromosome associated with Down syndrome.

“Quest integrates results from an ultrasound performed by a certified ultrasonographer produced at a physician’s office or in an imaging center with our laboratory results and other clinical information—patient age and medical history—to generate a risk assessment," she says.

Another instance where the in vivo and in vitro combination can be valuable is in identifying patients with pulmonary thrombosis. Physicians can use diagnostic test results for hypercoagulability (clotting disorders) and imaging results of a thrombus, or thickening of the heart’s left ventricle, along with an evaluation of a patient’s characteristics, such as gender and history of hypertension, to form an assessment.

“The convergence [of in vivo with in vitro] is likely to increase as imaging and diagnostic capabilities evolve, knowledge grows, and information technologies improve bridging different sources of information,” Schwartz says. “With these advances, the industry can expect to produce greater insights leading to better patient care.”

Just as automation has improved efficiencies and reduced costs, consolidation among major industry players, says Samuels, also generally improves efficiency and enables discoveries to be applied over a broader array of technologies.

“Assuming they help drive operating efficiencies, we expect the Siemens merger could promote lower costs,” Samuels says. “While we cannot anticipate changes in reimbursement that depend upon so many different factors, in general, lower costs can expand access.”

Consider Care360, a patient-centric physician portal from MedPlus, a Quest subsidiary. Care360 is used by more than 100,000 physicians’ offices to manage patient data, such as medical history, and to order and receive test results on the Internet. Usually, results of a test processed by a Quest laboratory can be made available to the physician’s office the next day using this system.

Nicholas Borgert is a contributing writer for CLP.