|

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)—also known as HR 1, “the Act,” and the stimulus—literally adds billions of taxpayer dollars to the health care mix. Signed by President Barack Obama on February 17, 2009, the ARRA seeks to boost health IT infrastructures in hopes of creating a nationwide health information network.

A cool $20 billion of the massive $728 billion ARRA is dedicated to electronic medical records (EMRs) and other health information technology projects. Electronic health records (EHRs) and EMRs have been a government priority for at least 5 years now, with the first significant mention coming in 2004 when President George W. Bush set a goal to get most Americans a personal EHR within a decade or less. The idea resembles the EMR push, but differences can be significant depending on the level of complexity that practitioners use.

|

While the additional stimulus money could conceivably translate into higher (and easier) reimbursement for clinical laboratories, Mark Birenbaum, PhD, administrator with the St Louis-based National Independent Laboratory Association (NILA), believes that scenario is unlikely. After all, most laboratories received a 4.5% consumer price index (CPI) increase to the part B fee schedule last year, a boost that took a decade to finally arrive.

“With Medicare trying to scramble to make ends meet, we would probably be doing well just to get our normal CPI increase this year,” Birenbaum says. “The only area where you might see some increase potentially is for some new tests [as a result of the stimulus] that could be added to the fee schedule.”

Another “back door” benefit for clinical labs could come via aid directed at major carmakers and construction companies. “If you provide money to save Chrysler or GM, and they use that to continue to pay their health care benefits, laboratory testing will be an inevitable part of those services,” Birenbaum adds. “As stimulus money goes toward construction projects, there is again an indirect benefit for labs, because with these new jobs will come health care benefits, and lab testing is part of these health care packages.”

EMR Integration—Biggest Impact?

The indirect flow of stimulus dollars is potentially significant, but the $20 billion allocated for EMRs and EHRs will likely represent the biggest impact. Lab directors and hospital officials have long been working toward the holy grail of seamless integration of lab results and physician records. The ARRA could make this dream a reality, and serve to help various clinical labs to hop on the digital bandwagon.

|

For those who have made little headway toward a satisfactory electronic system, aid could come in the form of incentive money. Other providers who have already spent a good deal of money on EMRs could also receive funds to upgrade to what will almost certainly be a universal standard that all labs will eventually have to meet. Scott Romney, marketing director for Intermountain Laboratory Services, Salt Lake City, counts his division as one of those early adopters. As of press time, Romney has received no direct communication from the government, and it appears he is not alone. In fact, many details have yet to be worked out, and HHS and other entities are sure to put out additional guidance to govern the new legislation.

The stimulus package does mention “meaningful use” as a necessity for health care providers who wish to avoid penalties that are sure to materialize after incentives have been drawn down. The message is clear: Government will help laboratories and other entities to adapt, but the alternative is to face financial repercussions that will likely come in the form of so-called negative “adjustments” to fee schedules.

The early talk is that the government will, in fact, pay to help paper-based facilities transition to EMRs. However, with so many levels of implementation, what will the money go for? “If you are using an EMR system to simply track patient flows, that is really not going to help you to boost clinical quality and improve outcomes,” says Ryan Smith, assistant vice president of e-business online services, Intermountain Healthcare. “And it certainly is not going to do much toward establishing what they call ‘meaningful use.’ “

Smith and Romney ultimately hope to shape the meaningful use debate on a national level. If they have anything to say about it, they want the term to encompass systems that truly help with clinical support and decision-making. “The data that you are storing in a meaningful system is actually coded, such that it can be actionable,” Smith says.

“The exchange has been set up between the practice, the hospital, the reference laboratories, and other providers of clinical data. That is a much higher level of implementation, and certainly should be incentivized at a higher rate if the government ends up doing some kind of tiered payment structure.”

Specifics are few, but there are some existing guidelines for meaningful use as defined in the stimulus package. In the broader realm of health care beyond the labs, meaningful use applies to non-hospital-based physicians and for hospitals. For non-hospital-based physicians, meaningful use includes the use of e-prescribing. More importantly for lab directors, meaningful use also encompasses the ability to use technology in a way that allows it to provide for the electronic exchange of information to improve quality—including the ability to submit information to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on clinical quality measures.

Birenbaum agrees that any laboratory must be able to successfully use an EMR system to interact with a large hospital and achieve the integration so highly prized by the industry. A uniform and standardized medical record is generally seen as essential to this goal.

“The physician will know if patients are being treated by three other doctors and what drugs they are on,” Birenbaum says. “If you just ask the patient, sometimes you get incorrect information. And sometimes, information is not up to date. There will be resistance from the patient as to how secure these records are. The system must also be opened so that providers can hook into it without massive investment and without arbitrary restrictions.”

So far, the concept of affordability has not been addressed by the government, but Birenbaum is adamant that cost concerns must be taken into account as the government seeks to outline the exact nature of the EMRs that laboratories will have to adopt. “If you adopt a new system that favors the big publicly traded corporate laboratories, or if you require a system where some labs can’t get into it without a massive investment, then basically you are putting a sector of laboratories out of business,” Birenbaum emphasizes. “Instead, we should find a way that businesses of all sizes can obtain this type of electronic record-keeping, and then be able to successfully transmit their information.”

|

|

Government subsidies via the stimulus bill are one way that Birenbaum hopes these concerns will be alleviated. He says that a standardized system will likely be required for EMRs to work effectively across a wide range of companies. “At some point, you are going to have to require everybody to use it,” Birenbaum muses. “In the past, information systems have been a way for labs to differentiate themselves in the competitive marketplace. But if the government is going to come in and say you must have an EMR, we have to make sure it is not a way to eliminate part of the market.”

Follow the Money

Government officials hope the widespread adoption of EMRs can prevent medical errors, provide better patient care, and introduce vital cost-saving measures. Keeping a conveniently close eye on providers to prevent fraud and abuse is another undeniable benefit. In the final analysis, billing mistakes (both intentional and unintentional) can result in government overpayments that lead to unwanted inquiries from bureaucrats.

“Today there is significant room for error, and electronic exchange capabilities between those that order and those that receive results can essentially make it a machine to machine transaction that will tremendously increase efficiency,” Smith says. “From a laboratory processing perspective, EMRs have big advantages, and they should all add up to being a positive thing for the industry in the long haul.”

“There are so many opportunities to make errors in the current process,” Romney adds, “from missed diagnosis codes to the wrong guarantor submitted with the lab order, all of which can result in billing errors or rejected claims. When you take this all out to the electronic medical record level, we expect many of those errors to go away.”

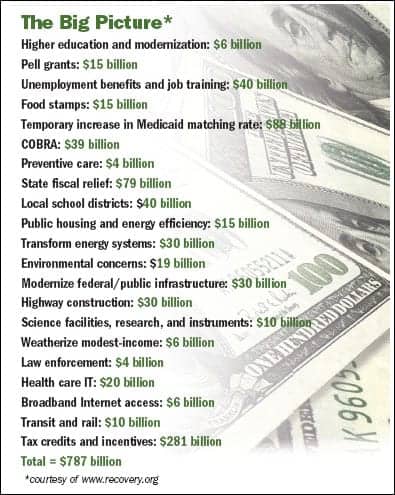

Parsing out the bill’s $787 billion finds roughly $112 billion devoted to three specific health care endeavors: 1) $88 billion for a temporary increase in state Medicaid matching rates; 2) $20 billion for health IT; and 3) $4 billion for preventive care and treatment evaluations.

Part of the $4 billion in element #3 includes $1.1 billion to compare drugs, medical devices (diagnostics fall into this category), surgery, and alternative ways to treat specific conditions. The bill creates a council of up to 15 federal employees to coordinate research and offer advice to the President and Congress concerning the best ways to spend the considerable funds.

As previously reported by CLP, funding is also allocated for comparative effectiveness (personalized medicine), pharmacogenetics, and more efficient diagnostic regimens. These dollars will likely spark additional research for molecular diagnostics and so-called individualized medicine. Obama has favored a personalized medicine approach in the past, so the confidence of personalized medicine advocates is not unfounded. In an age of swine flu and other diagnostic priorities, it remains to be seen as to whether government officials will continue to favor the personal approach.

NILA’s Birenbaum agrees that personalized medicine might be better for certain individuals, and while he calls it a laudable goal, he also points out that the health of the general public may shape up to be a bigger priority. “How do we prevent the widespread problems such as the flu epidemic and the emerging threats such as swine flu?” Birenbaum says. “Rapid screening tests are a priority for various types of diseases. Community labs tend to be the labs in which a lot of the unusual diseases are first spotted. It is important to have that early detection and to figure out what is going on quickly so you can contain the outbreak. Rapid testing allows you to quickly screen a lot of people. Developing new tests that enable more laboratories to type these organisms rapidly is also important.”

A promised infusion of funds to the National Institutes of Health is expected to fuel clinical diagnostics, possibly leading to new technologies, biomarkers, and additional trained personnel. If the NIH does an adequate job doling out the funds, Birenbaum agrees that new clinical and diagnostic tests could result. He believes that additional training of molecular biologists and molecular geneticists could also be a positive development.

When will all this happen? Echoing Bush’s 2004 speech, the stimulus bill specifically calls for EHRs for every American no later than 2014. In 2009, look for additional guidance as HHS seeks to illuminate the gray areas and provide details into what is still an evolving initiative.

Greg Thompson is a contributing writer for CLP.